I. Introduction

“Telling the truth about a given condition is absolutely requisite to any possibility of reforming it.”

-Barbara Tuchman (1912 - 1989, Pulitzer Prize-winning American historian and author)

“If I had an hour to solve a problem, I'd spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.”

- Albert Einstein (1879 - 1955)

College sports are at a critical juncture.

Athletes have made some progress since the spring and summer of 2021 with the Alston decision, the advent of a less regulated NIL marketplace, more flexibility for athletes to transfer, the recent movement toward employee status, and new litigation that appears to be beneficial to athletes.

But that progress is not guaranteed.

As explained below, the NCAA and Power 5 never wanted the current NIL or transfer markets to exist, and they are doing everything in their power to reclaim iron-fisted control over those—and every other—athlete compensation and recruiting markets.

Current athlete freedoms in NIL and transfer are the product of external regulatory threats, primarily from federal courts, not NCAA/Power 5 generosity. These markets exist in an unstable regulatory environment and are mainly the product of temporary interest convergence between athletes and institutions.

The NCAA and Power 5 are aggressively seeking to reclaim control of the legal and regulatory environments in college sports through a combination of strategic legal settlements and the powers of the federal government.

The NCAA and Power 5 have the best lawyers, lobbyists, and public relations experts in America doing their bidding.

To make sense of the regulatory and legal environments now in play, it is crucial to look at things the way the NCAA, Power 5, and their lawyers, lobbyists, and spin doctors do.

They are playing three-dimensional chess. The chessboard has become more complicated in the last year, but the NCAA and Power 5’s end game—regulatory supremacy—has not changed one bit.

But the NCAA and Power 5 know they are on the clock. They understand that the longer the current NIL marketplace exists and the more external regulators press for change on multiple fronts, the harder it will be for them to control their own destiny.

Note: A more specific assessment of the NCAA and Power 5’s current chessboard is contained in section “VI: A Modest Proposal” under the heading “The NCAA and Power 5 Chessboard as it Now Sits.”

Athletes must understand that they, too, are on the clock.

The NCAA and Power 5 are not going to throw up their hands and walk away from Congress, voluntarily recognize athletes as employees, or resolve pending legal actions on terms that don’t provide maximum benefit to them.

Athletes must suit up and get into the game on their terms, not on terms defined by the NCAA, the Power 5, Congress, lawyers, lobbyists, federal courts, and state legislatures.

Athletes cannot afford to be spectators and assume their interests are adequately represented at decision-making tables or that the current NIL and transfer markets are permanent fixtures in college sports

A Scouting Report for Athletes

We don’t presume to speak for athletes or suggest they should agree with our critique of college sports. Some athletes directly impacted by the recent changes in conference affiliations, for example, may think it’s a good thing.

Similarly, some athletes may agree with in-system stakeholders that athletes should not be employees, participate in revenue sharing, have access to federal courts and administrative agencies, or benefit from state legislation.

Some athletes may also be content with the new NIL and transfer markets and not motivated to speak up or rock the boat. They may not be all that concerned with what happens in two years or five years because they are focused on the financial benefits of the here and now.

Regardless of athletes’ starting point and how they see their interests, we do think that athletes should have (1) a meaningful voice in the decision-making processes that determine their relationship with institutional stakeholders and the quality of their experiences on the field and in the classroom and (2) a working understanding of the historical, structural, financial, institutional, political, and normative influences that shape the current regulatory and business models and the future of college sports.

To that end, DYK seeks to inform athletes and other stakeholders about where and how the game is being played and who is calling the shots.

The future of college sports isn’t being decided in academic settings among institutional stakeholders sitting around conference tables having thoughtful, inclusive, open-minded discussions about the values of college sports and higher education.

Instead, the real game is being played in federal courts, federal administrative agencies, state legislatures, Congress's backrooms, and secret meetings among the wealthiest stakeholders.

The most influential players are lawyers, lobbyists, public relations experts, broadcast media behemoths, and a very small group of institutional powerbrokers now dominated by SEC and Big Ten football interests.

The NCAA and Power 5 conferences are using every lever of power to shape the college sports legal, regulatory, and financial models to their liking.

Since 2019, when the NCAA and Power 5 formulated their congressional strategy to respond to California’s state NIL law, the NCAA and Power 5 have operated with a “crisis” mentality.

Indeed, some lobbying and public relations experts on the NCAA’s payroll specialize in “crisis management” and “crisis response.”

What is “crisis” for the NCAA and Power 5?

Being forced to comply with America’s free competition, federal labor, and state sports-related laws.

For the first time in college sports history, the NCAA and Power 5 must also contend with free markets operating for the benefit of athletes in the new NIL marketplace.

If the NCAA and Power 5 get their way, free market principles will yield to heavy-handed government regulation.

In this time of uncertainty and regulatory confusion, it is critical for athletes to understand that they cannot prematurely claim “victory” because things seem to be going their way.

They will have to fight for their basic rights to economic self-determination and a meaningful seat at the table.

Secret Decision-Making

Contrary to the NCAA's claims that its’ governance model is built around principles of “representative democracy,” the most important decisions regarding the current state and future of college sports are being made by a very small number of very powerful people outside of public view and outside college sports’ formal governance structures.

These elite decision-makers all benefit from the current business and regulatory models. They have the least incentive to change the system.

The recent formation of the Big Ten-SEC “Advisory Group” is a perfect example.

The Big Ten and SEC have segregated their interests from the rest of college sports and are poised to impose their will on the entire college sports landscape.

The Advisory Group’s very existence is an affront to NCAA governance philosophies and structures because it operates entirely outside them.

Yet NCAA members and leaders have little to say in response.

One thing is clear: there will be no meaningful reform or broad-based athlete input if the people and institutions who built the big-time college sports juggernaut have primary or exclusive control over its future.

Note: For a discussion on NCAA/Power 5 decision-making, see the “NCAA Governance” and “Power 5 Secret Society” materials accessible from the homepage.

Confusing Crosscurrents and Temporary Interest Convergence

In response to events in the spring and summer of 2021 (Alston, the NIL “Interim Policy,” failure to obtain federal protections and immunities from Congress, and the new transfer rules), the NCAA created a regulatory vacuum by choosing not to enforce its own rules.

It blamed its inaction on the absence of protective federal legislation.

As the NIL and transfer markets evolved and as external regulatory threats mounted, the NCAA’s self-imposed regulatory paralysis created an environment that led some Power 5 schools to aggressively pursue and protect their own interests in the ongoing battle to achieve—or avoid losing—a competitive advantage in recruiting.

Some Power 5 schools have influenced state legislatures and state attorneys general to shape state law and policy to match the schools’ immediate needs in the football and men’s basketball labor markets.

These initiatives—which include federal antitrust suits against the NCAA—are driven almost exclusively by chronic, irrational fears of losing a competitive advantage in recruiting.

Through the operation of temporary interest convergence, athletes appear to be “winning” more freedom in the transfer and NIL markets.

However, these confusing and situational regulatory crosscurrents mask the NCAA and Power 5’s ultimate goal of absolute regulatory supremacy over college sports.

Promises, Promises

The NCAA and Power 5 are attempting to convince stakeholders yet again that they sincerely want to “modernize” and “transform” their business model to align it with reality.

In December 2023, NCAA President Charlie Baker announced his vaguely defined “Project D-I,” which suggests a pathway to “revenue sharing” for the “highest resourced” institutions.

Other iterations of revenue sharing have surfaced, but it’s not clear exactly what they may entail.

Importantly, Baker and other institutional stakeholders discuss revenue sharing and other potential athlete benefits in tandem with federal protections and immunities that grant the NCAA and Power 5 absolute control over any revenue-sharing and athlete benefit model(s).

In this sense, as discussed below, new promises of revenue sharing and other athlete “benefits” are very similar to NCAA and Power 5 promises of NIL compensation going back to 2019 that served as nothing more than a Trojan Horse for absolute control over college sports’ legal and regulatory environments.

While there is a new NCAA leader making new promises, the tactic of promise and delay comes from a decades-old NCAA playbook.

The NCAA has been “modernizing” college sports for thirty years. Modernization that has benefitted athletes has come from external pressures, not intelligent, forward-thinking NCAA rules and policymaking.

Congress, Congress, Congress

The NCAA and Power 5’s congressional campaign (discussed below) began nearly five years ago and has made progress largely invisible to stakeholders and the public.

The endgame for the NCAA and Power 5 is unchallengeable regulatory authority. They seek legislation to eliminate from the regulatory field (1) federal courts (through antitrust immunity), (2) federal administrative agencies with jurisdiction over labor issues (by prohibiting athletes from being employees), and (3) state legislatures (through federal preemption that would nullify state laws).

While no bill has made it to a committee vote, many lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have bought into NCAA/Power 5-friendly equity-based narratives and scare tactics.

There is little evidence that the NCAA and Power 5 intend to abandon protective legislation, particularly as the threat of athletes becoming employees intensifies.

The NLRB’s decision in the Dartmouth case reinvigorated the NCAA and Power 5’s no-employee crusade in Congress.

NCAA and Power 5 lobbyists have made significant progress in Congress on that front.

Using divisive and unproven equity-based scare tactics, the NCAA and Power 5 want lawmakers to presume that employee status for athletes will force schools to wholesale eliminate women’s and other “Olympic” sports.

The NCAA and Power 5 are directing their no-employee campaign at a granular level to female Democrats, particularly those in labor-friendly states, and some appear to buy the NCAA and Power 5’s equity-based arguments.

The NCAA and Power 5 will fight and die on the no-employee hill.

As discussed below, the no-employee issue may have additional momentum if the NCAA and Power 5 reach a global settlement of the pending compensation-related antitrust cases.

Note: For a detailed discussion of athletes as employees and the NCAA and Power 5’s lobbying tactics on that issue, see the “Administrative Agencies” (specifically section III, “Labor and Employee Protections”) and “Lobbying” (section VI, “Where the NCAA’s and Power 5’s Congressional Campaign is Likely Heading”)

Note: For a detailed discussion of the role of Congress, see the “Congress” materials accessible from the homepage.

NCAA/Power 5 Plan B: A Global Settlement of House, Hubbard, and Carter

As a backup or complementary plan to a comprehensive federal bill, the NCAA and Power 5 are now considering a global settlement of three federal class action antitrust lawsuits—House, Hubbard, and Carter—filed by athletes challenging some or all NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits.

The same lawyers represent the athletes in all three cases.

The House case is set for trial in January 2025 and poses the most immediate threat to the NCAA and Power 4. According to the athletes’ lawyers, damages in House could exceed a billion dollars. In antitrust cases, an award of damages is automatically tripled.

Through a global settlement, the NCAA and Power 5 would pay a substantial amount (potentially north of $2 billion) to resolve athlete compensation issues and receive in return broad releases from past, current, and future liability for the anti-competitive behavior at issue in each suit.

If the scope of the releases is broad enough, the NCAA and Power 5 would essentially purchase antitrust immunity for the most vulnerable compensation-related aspects of their business model.

The settlement would also include some form of revenue sharing going forward for the current Power 4 conferences or schools.

Importantly, the global settlement discussions are occurring without global athlete input. What we know so far about the terms of any such settlement comes from selective leaks from anonymous “sources with knowledge” or from cryptic public comments from the athletes’ lawyers.

The evidence and expert opinions in the three cases that form the basis for settlement discussions have been placed under seal by consent of the parties and are not accessible to athletes, stakeholders, or the public.

The legal briefs in House explain the parties' key positions and synthesize the evidence with the legal theories and proposed compensation formulas. The athletes' most recent filing (April 3, 2024), in which they ask the court to rule in their favor on crucial legal issues, is virtually unreadable because huge chunks of the most crucial information have been redacted as a result of the secrecy orders.

The parties are in the process of coordinating the evidence and applying prior secrecy requirements from O’Bannon, Alston, and House to Hubbard and Carter. In a recent (April 29, 2024) NCAA motion to consolidate a Colorado case (Fontenot v NCAA) with Carter in California, the NCAA and Power 5 stressed judicial efficiency and the importance of coordinating evidence and secrecy orders across all pending antitrust cases.

The NCAA and Power 5 emphasized that consolidation of House, Hubbard, Fontenot, and Carter would allow “a number of pretrial issues to be resolve quickly,” suggesting urgency in positioning these cases procedurally for a single global settlement.

These procedural maneuvers position House, Hubbard, and Carter for a joint resolution of compensation issues.

Such a settlement could reenergize the NCAA and Power 5’s quest in Congress for preemption of state laws and a prohibition on athletes being employees of their university. Indeed, a lawyer for the athletes suggested that a settlement of House, Hubbard, and Carter could create a pathway for the NCAA and Power 4 to receive protective federal legislation.

This scenario carries profound implications for athletes in the future. It's crucial to note that an antitrust settlement alone will not adequately address athlete issues on health and safety, work conditions, and effective representation.

If Congress steps in after a global settlement on compensation issues and passes a law that prevents athletes from being employees, athletes will forever be denied to the protections of federal labor laws, including potential collective bargaining under the National Labor Relations Act.

Just as athletes have had to force the NCAA and Power 5 to change through antitrust litigation on compensation and eligibility issues, they will likely have to force the NCAA and Power 4 to a bargaining table on health and safety, work conditions, and meaningful athlete representation. Without the possibility of some form of formal, enforceable collective bargaining, athletes are left at the mercy of the very institutional interests that have consistently refused to protect athletes.

In a post-settlement environment, Congress could also provide additional antitrust protection to the NCAA and Power 4 on top of what they would obtain through a global settlement and sweeping releases from liability. Similarly, Congress could limit the role of state legislatures through federal preemption.

Importantly, all of these issues could be addressed in enforceable colective bargaining through which the NCAA and Power 4 may be able to obtain the very antitrust protection they so desperately want through a nonstatutory labor antitrust exemption.

Note: For a detailed discussion of the role of federal courts in college sports, see the “Federal Courts” materials accessible from the homepage.

A. The NIL Debate: A Case Study in NCAA and Power 5 Mass Manipulation

An analysis of the evolution of the NIL debate illustrates how the NCAA and Power 5 have manipulated the NCAA governance process, the federal court system, Congress, state legislatures, and the media to achieve buy-in to patently false narratives that serve NCAA/Power 5 regulatory and business interests.

The NCAA and Power 5 have employed the best lawyers, lobbyists, and public relations experts in the business in their attempt to pull off one of the most audacious and sophisticated regulatory coups in American sports history.

The massive firepower the NCAA and Power 5 bring to this fight is funded from revenue generated by the very athletes—Power 5 football and men’s basketball players—whose rights are at greatest risk.

Throughout the five-year debate on NIL, the NCAA and Power 5 have persuaded decision-makers, stakeholders, and the public that they fully support “NIL compensation” for athletes.

Indeed, many credit the NCAA for fulfilling its promises of “NIL compensation” and attribute the existing market to NCAA magnanimity and foresight.

In fact, the NCAA and Power 5 have fought NIL compensation every step of the way, first trying to prevent the NIL market from coming into existence and, when that failed, trying to rein it in.

Under the guise of “NIL compensation,” the NCAA and Power 5 engaged Congress to ask for sweeping federal protections and immunities unprecedented in college sports—preemption of state NIL laws, antitrust immunity, and nonemployee status for athletes—that would eliminate all external threats to the NCAA and Power 5’s regulatory authority and business models.

These protections and immunities go far beyond any legitimate “NIL compensation” issue.

In Alston, the NCAA sought an expansive judicially created antitrust immunity on the grounds that as the guardians of the sacred principle of “amateurism,” they should operate above our nation’s free competition laws.

Note: For more analysis of the history and purpose of the NCAA and Power 5’s use of NIL as a justification for receiving sweeping federal protections and immunities from Congress, see the materials in Section IV of Critical Questions (Who Gets to Decide?) and the Congress Tab materials accessible from the homepage.

1. The NCAA and Power 5’s Initial Response to NIL

Two events triggered the NIL debate and the NCAA and Power 5’s response to it.

First, on February 5, 2019, California State Senators Nancy Skinner and Steven Bradford introduced SB 206 (“The Fair Pay to Play Act.”) that provided NIL compensation opportunities for college athletes in California.

SB 206 was the first state-based NIL proposal, and it directly challenged and conflicted with the NCAA’s NIL compensation prohibitions contained in NCAA By-Law 12.

Yet SB 206 was in many ways deferential to the NCAA’s conceptualization and use of amateurism. It prohibited using NIL as pay-for-play or as a recruiting inducement. Additionally, NIL deals could only made with third parties, not universities.

The NCAA and Power 5 portrayed SB 206 as an existential threat to NCAA core principles and to all of college sports.

The NCAA initially responded to SB 206 by threatening to declare athletes in California ineligible if they took advantage of the law's benefits.

The NCAA Board of Governors and NCAA attorneys also made veiled threats to sue California under the Constitution’s Commerce Clause to nullify SB 2026.

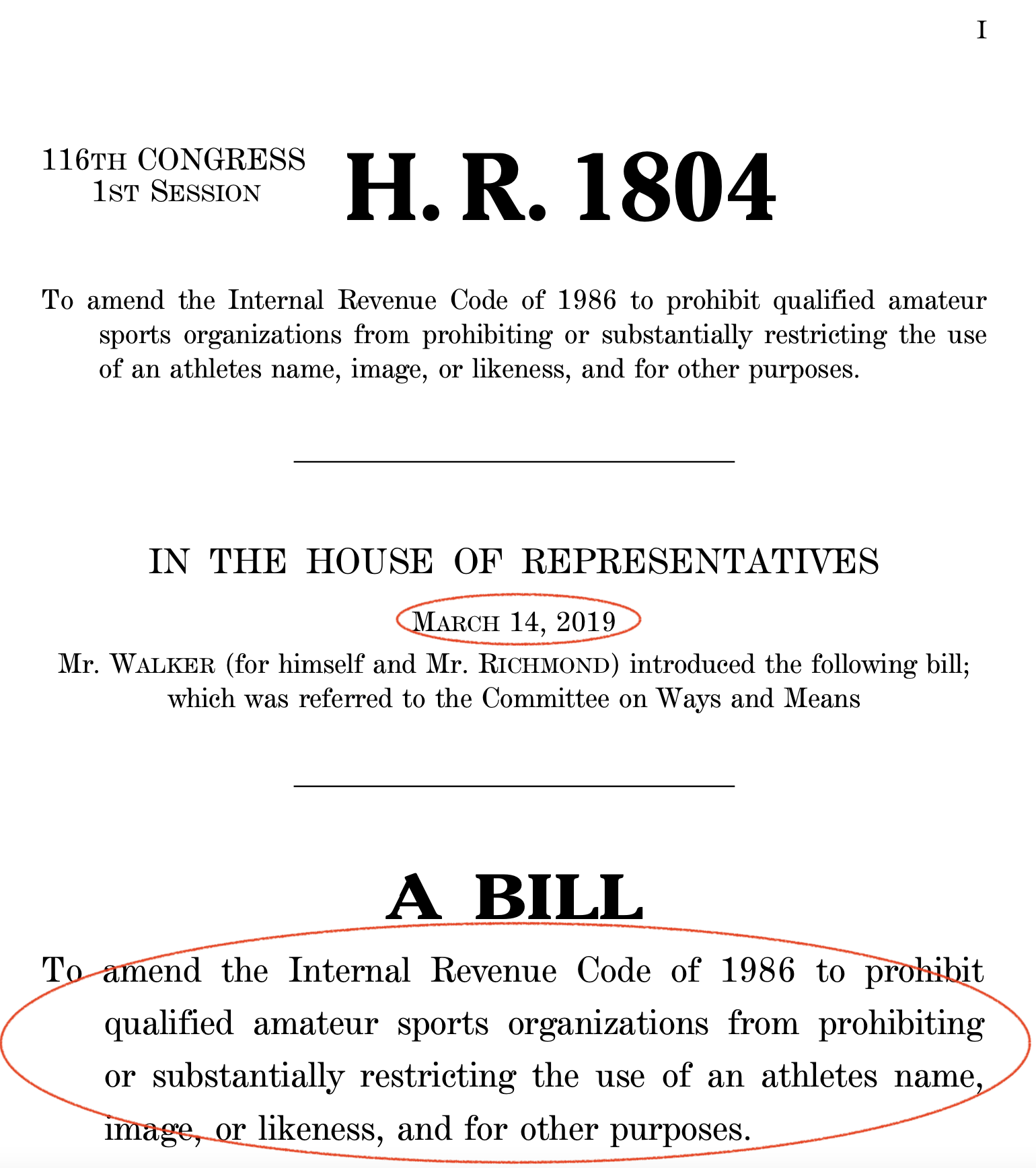

Second, on March 14, 2019, Representatives Mark Walker (R-NC6) and Cedric Richmond (D-LA2) introduced a bipartisan bill titled the “Student-Athlete Equity Act.”

The bill would strip the NCAA of its nonprofit status unless it offered “reasonable” NIL compensation opportunities to athletes.

The NCAA responded to the Walker bill through a public relations smear campaign, portraying the bill as an existential threat to college sports.

NCAA leaders refused to meet with Walker.

2. False Promises on NCAA NIL Rule Changes and Congressional Engagement

SB 206 and the Walker bill led the NCAA to formulate a comprehensive strategy to commandeer the NIL debate and use it to protect their regulatory and business models.

The strategy ran through three intertwined pathways: promises of voluntary NCAA rule changes on NIL, Congress, and Alston.

To that end, on May 14, 2019, the NCAA formed the NCAA Board of Governors Federal and State Legislation Working Group (Working Group) to explore whether the NCAA should continue its blanket opposition to NIL compensation or instead consider more permissive NIL rules.

The Working Group ultimately devised a cynical strategy to lead the public to believe that it was moving forward with voluntary NIL rule changes while at the same time seeking legal protections and immunities through Congress or Alston that would allow the NCAA to do nothing on NIL.

a. NCAA Pushback to SB 206

Between the Working Group’s formation in May 2019 and SB 206’s enactment in September 2019, the NCAA and Power 5 schools in California pushed for changes to the law to bring it more in alignment with NCAA amateurism principles.

The NCAA emphasized its claimed intent to voluntarily change its NIL rules to permit meaningful NIL compensation.

The NCAA argued that it should be left alone to self-regulate on NIL without interference from states.

On May 17, just three days after the Working Group was formed, the California legislature added a crucial—and initially unexplained—limitation to SB 206: it would not go into effect until 2023.

On June 17, 2019, NCAA President NCAA President Mark Emmert sent a letter to committee chairs in the CA Assembly asking them to “postpone further consideration of Senate Bill 206…while we review our rules.” Emmert again emphasized the creation of the Working Group and its study “of potential processes whereby a student-athlete’s NIL could be monetized in a fashion that would be consistent with the NCAA’s core values, mission, and principles.” (emphasis added)

When the final version of SB 206 was released, the preamble explained the reason for the delayed effective date:

“It is the intent of the legislature to monitor the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) working group created in May 2019 to examine issues relating to the use of a student’s name, image, and likeness and revisit this issue to implement significant findings and recommendations of the NCAA working group in furtherance of the statutory changes proposed by this act.”

Thus, California gave the NCAA four years to formulate and adopt NIL rule changes to benefit athletes.

That promise was never fulfilled.

To this date, the NCAA has not changed a single word of a single NCAA rule governing NIL. (see discussion of the NCAA “Interim Policy” below)

Note: For a full discussion of the history and impact of SB 206, see the “State Legislatures” Tab (Section VI: State Name, Image, and Likeness Laws) on the homepage.

On October 23, 2019, the Working Group issued an interim report outlining a pathway to “NIL compensation.”

But there was a catch.

The NCAA insisted that any voluntary rule changes had to be aligned with the “NCAA’s core values, mission, and principles.”

In other words, the NCAA would only offer NIL compensation within amateurism-based principles that prohibit compensation.

On October 29, 2019, the NCAA Board of Governors adopted the Working Group’s recommendations and led stakeholders and the public to believe that it would voluntarily change its NIL rules by January 2021 to coincide with the NCAA annual convention.

Some prominent media outlets hailed the Board of Governors’ blessing of the Working Group’s interim report as an actual rule change.

For example, on October 31, 2019, the Wall Street Journal published a front-page article titled “NCAA Alters Rules On Athlete Income.”

As the conditional, fine print language of the interim report’s recommendations indicates, the NCAA did no such thing.

However, the NCAA was content to leave the WSJ’s and other similar articles’ inaccurate characterization unchallenged.

b. The Origins of the NCAA and Power 5’s Congressional Campaign

On November 16, 2019, the NCAA Board of Governors Executive Committee quietly instructed the Working Group to form the Presidential Subcommittee on Congressional Action (PSCA).

The existence of the PSCA was not made public until the Working Group issued its Final Report on April 17, 2020.

The Executive Committee’s charge to the eight-member PSCA was to “provide input to the Board of Governors and the NCAA President on potential assistance that the Association should seek from Congress to support any efforts to modernize the rules in NCAA sports, while maintaining the latitude that the Association needs to further its mission to oversee and promote intercollegiate athletics on a national scale.”

On December 5, 2019, Senators Chris Murphy (D-CT), Cory Booker (D-NJ), Mitt Romney (R-UT), Marco Rubio (R-FL), and David Perdue (R-GA) announced the formation of a bipartisan working group on athlete compensation.

This bipartisan coalition of influential Senators posed a potential threat to NCAA and Power 5 regulatory authority and motivated the Power 5 to formulate an aggressive strategy to commandeer and navigate any congressional activity on college sports, including the possibility of NIL compensation.

On December 10, 2019, in response to the announcement of the Senate coalition, Power 5 leaders convened a secret teleconference outside the NCAA governance structure to formalize a strategy for congressional engagement.

Fifteen people were on the call, all either Power 5 conference commissioners or Power 5 university presidents/chancellors.

NCAA President Mark Emmert was not invited to participate.

The meeting minutes (obtained by journalist Andy Wittry through public records requests) show that the bipartisan Senate working group was a precipitating factor for the meeting (“If we want to have influence, all major players in college sports and stakeholders need to be coordinated. Last week’s announcement by a group of bi-partisan Senators emphasizes this fact…[a]ll of us have spoken with different Senators and members of Congress interested in this issue, and with the formation last week of the bi-partisan group of Senators, we believe the time is now to get our act together.”)

(Note: “Autonomy 5” is the same as Power 5)

Michael Drake led the meeting, and former Pac-12 conference commissioner Larry Scott took the minutes.

The meeting outlines the Power 5’s playbook for controlling Congressional engagement, messaging, and narratives.

The rest of the minutes are set forth below, followed by key themes that emerged and continue to influence the NIL debate today.

c. Foundational Themes from the Secret Meeting

i. Power 5 Unity and Coordinated Messaging

* “work together to launch a coordinated strategy”

* “critical to be coordinated and aligned”

* “cannot have mixed messages”

* “all major players in sports and stakeholders need to be coordinated” (emphasis added)

* “hire a Washington-based public affairs firm…this firm will serve as the campaign manager or quarterback”

* “effort would be jointly managed by all five conferences”

* “great advantages of hiring one firm – it will help us navigate the process, keep good coordination among the 65 universities, serve as a central hub for our messaging materials, and help deploy the right resources at the right time”

ii. Urgency to Commandeer the Debate

* “…we have urgency here.”

* “While there are different thoughts on whether a bill could go forward in this next year, it is very clear that forums are already being held and opinions are being shaped right now.” (emphasis added)

* “All of us have spoken to different Senators and Members of Congress interested in this issue, and with the formation last week of the bi-partisan group of Senators, we believe the time is now to get our act together.”

* “We need to be coordinated, and we need to be ready.”

iii. Call the Shots but Disguise Power 5 Involvement

* “…as we have done with Autonomy, we think the 65 schools that make up our conferences should take the lead in this effort” (emphasis added)

* “[b]ut we don’t think that it is advisable to brand this as a [Power 5] effort” (emphasis added)

* “we don’t think Mark [Emmert, NCAA President] should be taking the lead in Congress”

* “the feedback we hear in Washington is that the NCAA does not have a good reputation with Senators or members of Congress”

* “the presidents and our government affairs leaders [lobbyists] at our 65 universities have ongoing relationships with these Senators and Members of Congress. These are the relationships that matter,

* “the Members and Senators care more about their state universities and what they bring to their states and constituents much more than they care about our national trade association.” (emphasis added)

* “we don’t want the NCAA to feel threatened or sidelined – this will require diplomatic discussions, and at some appoint, this will require a group of presidents and commissioners sitting down with Mark [Emmert]”

iv. Manipulate the Language to Devalue Athlete Interests

* rather than “NIL rights…we would prefer to call [NIL] ‘collegiate licensing opportunities’ for our student-athletes.”

* “we believe it is important to frame it as licensing opportunities for student-athletes within the college system, and not some inherent natural right.” (emphasis added)

v. Eliminate External Regulatory Threats: Preemption of State Laws, Antitrust Immunity, and Athletes Cannot be Employees

* “don’t want this new collegiate licensing regime to enable boosterism or to be a vehicle for pay to play”

* “we don’t want students to be turned into employees – they must remain students.”

* “Importantly, the bill will also have to give us and the NCAA the ability to enforce NCAA rules AND keep us from facing numerous lawsuits”

* “What we’ve initially heard through discussions with legislators in Congress is that we should stay narrow and focus on developing legislation that fits with the foundational principles we want to preserve in college sports. This message has resonated with reasonable legislators and may be our best path forward.” (emphasis added)

Note: For a full discussion of Power 5 secret decision-making, see the “Power 5 Secret Society” Tab on the homepage.

d. The First Congressional Hearing

Two months later, on February 11, 2020, Congress held the first hearing ostensibly on “NIL compensation” in the Senate Commerce Subcommittee on Manufacturing, Trade, and Consumer Protection chaired by Jerry Moran (R-KS).

Senator Roger Wicker (R-MS) chaired the parent Commerce Committee and attended the hearing.

Wicker and Moran would become among the most influential voices in Congress throughout the “NIL compensation” debate. They both adopted and aggressively pursued the Power 5/NCAA agenda and introduced bills that contained everything on the Power 5/NCAA wish list—preemption, antitrust immunity, and nonemployment status for athletes.

Six witnesses testified. Five offered testimony favorable to NCAA and Power 5 interests and flooded the hearing with NCAA/Power 5-friendly talking points. Among the NCAA/Power 5 witnesses were House member Anthony Gonzalez (R-OH), NCAA President Mark Emmert, Big 12 conference commissioner Bob Bowlsby, and University of Kansas Chancellor Doug Girod.

This hearing was among the most consequential events in the five-year evolution of Congressional involvement, ostensibly on NIL.

It marked the Power 5 and NCAA’s hostile takeover of debate on college sports reform.

Through this hearing, the Power 5 and NCAA successfully set the terms of the debate, defined the language, and created the illusion of consensus on NIL-related issues through a stacked witness panel.

Through disingenuous claims of support for “NIL compensation,” the Power 5 and NCAA laid the foundation for using NIL as a Trojan Horse for preemption, antitrust immunity, and nonemployment status for athletes.

Importantly, too, the hearing effectively marked the end of bipartisan cooperation on college sports reform. The bipartisan coalition fell apart, and its members wound up on opposite sides of the debate.

Senators Marco Rubio and Mitt Romney promoted Power 5/NCAA interests, and Senators Chris Murphy and Cory Booker promoted athlete interests.

On June 18, 2020, Marco Rubio introduced the first piece of legislation on NIL. It offered little in terms of NIL benefits and gave the NCAA and Power 5 sweeping federal protections and immunities.

The NCAA lauded the Rubio bill on its website the day it was released.

e. The Working Group’s Final Report

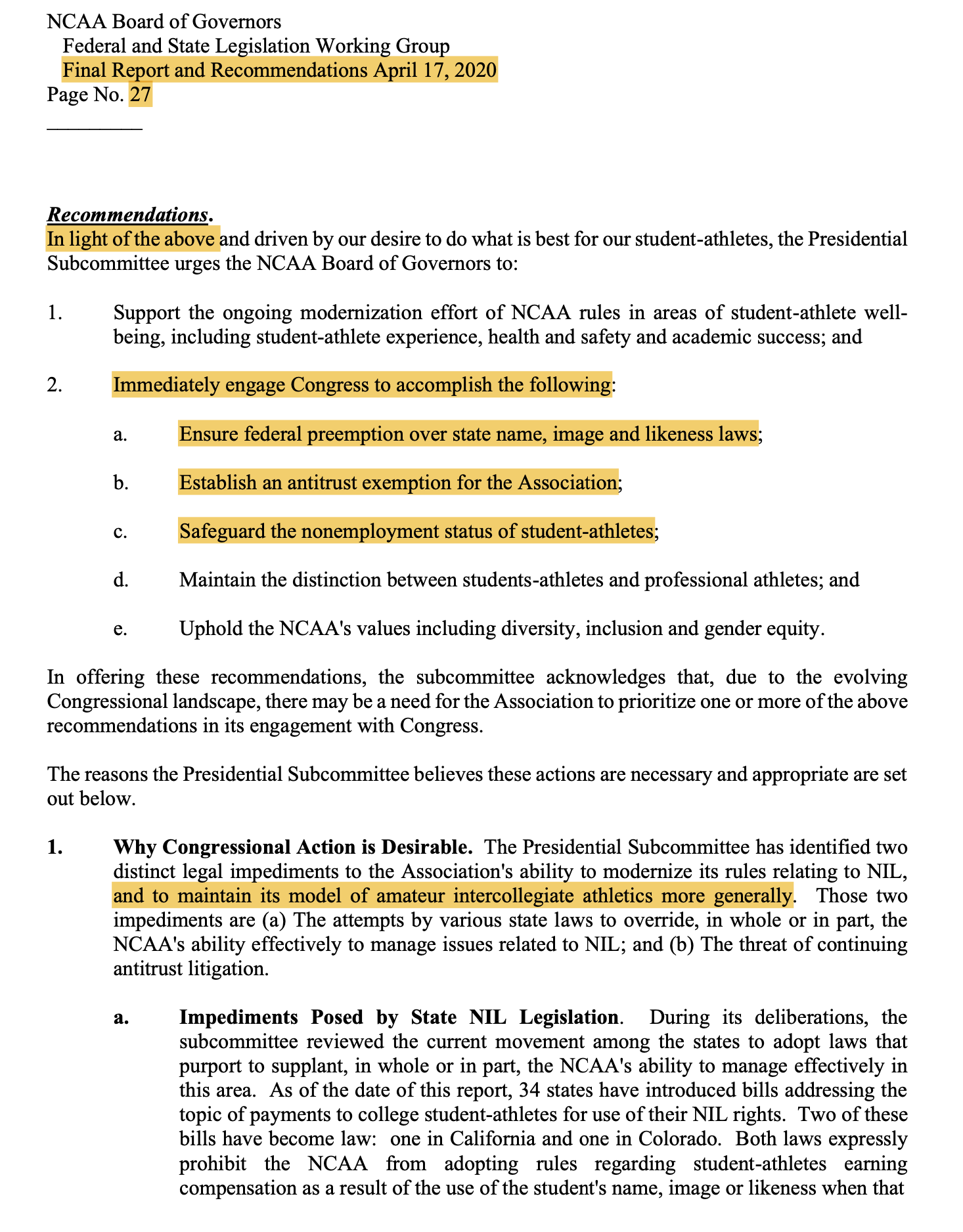

On April 17, 2020, the Working Group released its Final Report.

The Report contained a section on the PSCA's work.

The PSCA recommended that the NCAA “Immediately engage Congress to accomplish the following:

a. federal preemption over state name, image, and likeness laws;

b. Establish an antitrust exemption for the Association;

c. Safeguard the nonemployment status of student-athletes;

d. Maintain the distinction between student-athletes and professional athletes…” (emphasis added)

The PSCA’s April 2020 recommendations align perfectly with the agenda items from the Power 5’s December 10, 2019, secret meeting.

Moreover, the PSCA’s exhortation that the NCAA “immediately engage” Congress was disingenuous because the NCAA and Power 5 had already engaged Congress.

The Final Report does not mention the February 11, 2020, hearing in the Senate.

f. The NCAA and Power 5’s Lobbying Army

By the time the Final Report was released, all Power 5 conferences had onboarded some of the best lobbying firms in Washington, D.C.

The NCAA already had the top lobbying firm, Brownstein Hyatt, doing its bidding. It also had its in-house lobbying team—the NCAA Office of Government Relations—on the job.

The Power 5 added eight more lobbying firms.

By April 2020, over fifty lobbyists were working behind the scenes to push the NCAA/Power 5 agenda.

These lobbying firms coordinated a sophisticated strategy to persuade Congress to pass legislation containing the Power 5 and the NCAA’s wish list of preemption, antitrust immunity, and unemployment status for athletes.

The Senate conducted three more hearings in 2020 leading up to the January 2021 deadline for NCAA voluntary rule changes on NIL.

These hearings occurred in a Republican-controlled Senate and ran through the Commerce, Judiciary, and Health, Education, and Labor Committees chaired by Roger Wicker (R-MS), Lindsey Graham (R-SC), and Lamar Alexander (R-TN), respectively.

These are the committees through which the NCAA would obtain preemption (Commerce), antitrust immunity (Judiciary), and no-employee status (HELP).

All three committee chairs were openly hostile to any NIL market not under NCAA control.

Note: For a full discussion on Congress’ role in regulating college sports, see the “Congress” Tab on the homepage.

B. Alston, the November 2020 Elections, and the End of NCAA Voluntary Rule Changes on NIL

1. Alston and the November Elections

The Alston antitrust case moved along the same track as the NCAA/Power 5 campaign in Congress.

It potentially provided the NCAA and Power 5 an alternate pathway for antitrust immunity.

On March 8, 2019, after a full bench trial, the district court found that the NCAA’s limits on certain education benefits violated federal antitrust laws and issued a modest injunction that permitted but did not require education benefits up to $5,980 per athlete per year for Power 5 conference athletes.

Despite the limited relief, the NCAA appealed to the Ninth Circuit.

On May 18, 2020, the Ninth Circuit upheld the district court’s decision in all respects.

On October 15, 2020, the NCAA appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, unmasking its quest for an amateurism-based, judicially created antitrust immunity—the “Holy Grail” of its congressional campaign.

In the November general elections, the Senate hung in the balance and would be determined by two Georgia special elections set for January 5, 2021. The NCAA’s Republican advantage in the Senate was at risk.

On December 16, 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court announced it would hear the Alston case, creating a pathway for a possible antitrust exemption for the NCAA.

Note: For a full discussion of Alston and its implications, see the “Federal Courts” Tab (Section IV: The Legal Firewall the NCAA and Power 5 Have Built Through Federal Litigation) on the homepage.

The January 5, 2021, Georgia special elections both went to Democrats, resulting in a Democrat-controlled Senate.

On January 8, just days before the NCAA convention and the presentation of NCAA rule changes on NIL, a story broke that the head of the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division, Makan Delharim, instructed the NCAA to halt its voluntary rule changes on NIL (and transfers).

According to the NCAA and Mark Emmert, Delharim and the DOJ’s Antitrust Division raised antitrust concerns with the proposed NIL and transfer rule changes.

The NCAA immediately ceased its voluntary rulemaking using Delharim’s admonition as its primary excuse.

On June 21, 2021, the Supreme Court issued its unanimous decision denying the NCAA judicially created antitrust immunity.

In a podcast interview on June 24, 2021, just three days after the Alston decision, Makan Delharim said that he had not instructed the NCAA to stand down on voluntary NIL and transfer rule and explained the NCAA’s true motivations for going back on its promises:

"And it reminds me…that in December or January when they had a meeting to adopt the transfer rules and name, image, and likeness rules. They were going in a certain direction, and you know, this is a matter of public record now. I had written a letter to Dr. Emmert and said, you know, the antitrust division was concerned about some of the changes, make sure you guys change it consistent with the antitrust laws. That was largely it.

And the transfer rules were frankly long overdue about some of the changes, some of the restrictions they put on schools for student-athletes to transfer after a year or two, you know, they have to go seek permission before they even go engage on it in a school they want to transfer to…and it's just, offensive restrictions that shouldn't exist.

But they delayed it, saying, oh, they delayed because of the Justice Department's concerns. And that just wasn't true.

They were planning on delaying it because the Supreme Court granted cert. on the Alston case.

So they thought they're going to get a shot, you know, a free shot in the goal, so to speak, and get some kind of an antitrust immunity, and therefore they don't have to make any changes to NIL.” (emphasis added)

The NCAA continues to justify its decision to abandon voluntary NIL rulemaking on Delharim’s and the DOJ’s claimed instruction to stand down.

While Delharim did not mention the Senate's flip from Republican to Democrat, it was undoubtedly an important consideration in the NCAA’s cessation of voluntary NIL rulemaking.

2. The NCAA’s Last-Ditch Attempts to Nullify State NIL Laws

As other states began passing NIL laws set to go into effect on July 1, 2021, the NCAA and Power 5 ramped up their congressional campaign to nullify those laws.

On June 9th, 2021, the Senate Commerce Committee held a hearing to allow the NCAA and Power 5 the opportunity to make their case for last-minute preemption of state laws.

In a stacked witness panel on the preemption issue, five witnesses testified in favor of preemption, and only one opposed it.

However, the US Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in the Alston on June 21, 2021, denying the NCAA’s request for judicially created antitrust immunity, effectively killed the NCAA’s last-minute push for preemption.

3. The “Interim Policy” and a Temporary NIL Market

On June 30, 2021, with no federal bailout, the NCAA announced its “Interim Policy” on NIL that permitted some NIL activity but prohibited pay-for-play and recruiting inducements.

The Policy applies to schools in states with no NIL law or executive order.

Soon thereafter, former NCAA President Mark Emmert tried to pitch the Interim Policy as a victory for athletes made possible by the NCAA and his change-oriented leadership philosophy.

In reality, the “Interim Policy” exists despite the NCAA and Mark Emmert, not because of them.

Moreover, while hailing the Interim Policy as a historic milestone for athletes, NCAA governance leaders from all three Divisions invoked a crucial and underreported asterisk: the need to “work with Congress to adopt federal legislation [on NIL] to support student-athletes.”

4. Renewed Efforts in Congress

Before the ink was dry on the Interim Policy, the NCAA aggressively pressed Congress for protective federal legislation that would have given the NCAA the authority to eliminate or substantially curtail the new NIL market.

On September 30, 2021—just three months after the Interim Policy went into effect—Emmert and Baylor President Linda Livingstone (also a member of the NCAA Board of Governors and the Division I Board of Directors) testified at a House hearing arguing that the new NIL market was a threat to the integrity of college sports.

Both Emmert and Livingstone emphasized the need for protective federal legislation so the NCAA could control the NIL market.

Emmert and Livingstone’s doublespeak on NIL highlights a crucial component of the Interim Policy that received scant attention and analysis when it was released.

The Policy’s primary “interim” condition was federal legislation that would grant the NCAA and Power 5 absolute authority over the NIL marketplace without legal consequence.

The “Interim Policy” was, by its very definition, temporary.

Accordingly, the NCAA and Power 5 have always viewed the NIL market itself as temporary until they regain as much control over it as Congress and states permit.

The NCAA and Power 5 were never sincere in their claimed desire for athletes to have “NIL compensation.”

They would only support NIL compensation in a NIL market they had absolute power over.

Some NIL laws that became effective on July 1st, 2021, channeled the NCAA’s temporary approach to the NIL market.

For example, Georgia’s NIL law would remain in effect until the earlier of:

(1) Federal legislation regulating NIL.

(2) NCAA NIL rules changes.

(3) June 30, 2025.

Similarly, the preamble to Texas’ NIL law acknowledged it was a temporary measure to avoid a competitive disadvantage in recruiting pending a federal NIL law.

Several states entered the NIL space through interim and emergency executive orders emphasizing the importance of remaining competitive in recruiting.

For example, on July 2, 2021, North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper signed Executive Order No. 223 that said, “WHEREAS, enacting immediate measures that would allow student-athletes to seek and receive compensation for commercial use of their name, image, and likeness will prevent the State of North Carolina from being at a competitive disadvantage in regard to enrollment at postsecondary educational institutions within the state.” (emphasis added)

The Executive Order was to remain in effect “until superseded by state or federal law…”

C. Temporary Interest Convergence Between Athletes and Institutions in the Dysfunctional Post-Interim Policy Regulatory Environment

Athlete “progress” since the Interim Policy has been driven in large measure by a temporary convergence of interests between athletes and institutions.

This interest convergence exists in an unstable regulatory environment created by the NCAA and Power 5 themselves.

1. State NIL Laws

Many states have repealed or substantially amended their NIL laws to create as much flexibility in the marketplace as possible and avoid a competitive disadvantage in recruiting.

For example, on April 15, 2021, Alabama passed a NIL law that was among the most restrictive in the country. It was built around amateurism-based principles to protect the “integrity” of college sports.

It contained criminal penalties for non-athletes who violated the law, and a prior version of the bill made it a crime for athletes to receive NIL compensation in violation of the law.

However, having a NIL law permitted schools in Alabama to pitch the law as a benefit to recruits.

On February 3, 2022, just ten months after its passage and seven months after the Interim Policy went into effect, Alabama repealed its NIL law in a three-paragraph bill.

The motivating concern for the Alabama legislature was a fear that states that did not have a NIL law or executive order and, therefore, operated under the more permissive Interim Policy were at a competitive advantage in recruiting.

When Alabama and Auburn faced a potential recruiting disadvantage, the state legislature flushed the bill and its integrity-based NIL “gurardrails” down the toilet faster than you can say Tuscaloosa.

Additionally, states with NIL laws or executive orders have done nothing to enforce them against in-state schools out of fear that an enforcement action may create a competitive disadvantage for that school.

In response to follow-up questions after an October 17, 2023, hearing in the Senate on “NIL compensation,” NCAA President Charlie Baker said the NCAA wasn’t aware of a single state NIL-related enforcement action.

Additionally, in 2023, several states —including Texas—amended their NIL laws to deter the NCAA from enforcing its NIL restrictions against in-state schools and athletes.

Similarly, the NCAA has been reluctant to enforce its own NIL-related rules, policies, and “guidance.”

The NCAA’s regulatory paralysis has been substantially influenced by how Power 5 schools have positioned themselves for competitive advantage purposes in the maturing NIL marketplace.

Power 5 schools are so afraid of being at a competitive disadvantage in recruiting that they will do almost anything to prevent it.

Competitive advantage/disadvantage derangement syndrome drives every discussion on athlete “benefits” and college sports reform efforts.

Importantly, the obsession with competitive advantage-disadvantage is focused mainly on an institution’s immediate needs in the athlete labor market, not what’s best for athletes or college sports in the long run.

2. The Tez Walker Case

In the early fall of 2023, UNC challenged NCAA transfer limitations to allow a single athlete to play for the Tar Heels football team.

The athlete, Tez Walker, was an NFL-caliber wide receiver who would add immediate firepower to UNC’s offense.

According to the NCAA, Walker has already used his one-time transfer and could only transfer and play right away if he met an NCAA transfer waiver exception.

Walker had a strong case for a waiver, citing mental health concerns and a desire to be closer to his ailing grandmother in North Carolina.

Moreover, Walker had an excellent academic record, achieving a 3.7 GPA at his prior schools.

After reviewing UNC’s case for a waiver, the NCAA denied it and required Walker to sit out a year before being eligible to play.

In response, UNC’s president, athletics director, and head football coach directed a public relations campaign against the NCAA’s decision.

As the public spat became increasingly confrontational, North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein intervened on behalf of UNC and Walker.

On September 26, 2023, Stein sent a letter to NCAA President Charlie Baker outlining his concerns over the NCAA’s denial of Walker’s waiver request.

In addition to making the case for Walker under the waiver criteria, Stein also made a compelling case that the NCAA’s decision raised antitrust issues.

Using the Alston antitrust framework, Stein applied a hypothetical rule of reason analysis to conclude the NCAA’s decision with respect to Walker violated federal and North Carolina antitrust laws.

Stein went a step further and argued that the NCAA’s transfer restrictions in general, rather than as applied to Walker, violated state and federal antitrust laws.

Soon after Stein’s letter, the NCAA granted Walker’s waiver, and he became immediately eligible to play.

The Walker case raises important issues regarding the current dysfunction in college sports regulation.

First, institutional stakeholders are willing to change their values and views on a dime to address a perceived competitive advantage-disadvantage concern.

After the Interim Policy went into effect in July 2021, UNC head football coach Mack Brown consistently and publicly criticized the NCAA’s one-time transfer rule as being too permissive.

Like many Power 5 football and men’s basketball coaches, Brown believed transfer portal freedoms led to unsustainable roster instability.

UNC athletic director Bubba Cunningham made similar comments (and also complained about NIL compensation).

Those values-based arguments seemed less important when Brown needed the immediate eligibility of a star player.

Second, while UNC framed its argument in part around concerns for Walker’s mental well-being, his eligibility served mainly institutional interests.

The benefit to Walker was incidental to that primary purpose and a product of temporary interest convergence.

Is it likely that UNC and the State Attorney General would have marshaled the full power of the state government to intervene on behalf of a football player situated identically to Walker on waiver criteria if that player was third on the depth chart as his position?

3. Lawsuits by States Fueled by Competitive Advantage-Disadvantage Concerns and Temporary Interest Convergence

In December 2023 and January 2024, several states with prominent Power 5 schools filed federal lawsuits against the NCAA, pressing for more freedom in the NIL and transfer markets.

On December 7, 2023, a group of states with high-profile Power 5 schools filed a federal antitrust suit challenging the NCAA’s one-time transfer restrictions. These states included Tennessee, Ohio, North Carolina, and West Virginia, all of which have Power 5 schools petitioning the NCAA to permit certain elite athletes who had used their one-time transfer to transfer again without penalty.

Channeling the reasoning in Josh Stein’s September 2023 letter to the NCAA, the states made a compelling antitrust case against the NCAA’s transfer limitations.

On December 12, 2023, the district court judge issued an order granting the states’ motion for temporary injunctive relief preventing the NCAA from enforcing its transfer restrictions pending a final ruling on the merits of the case.

On December 15, 2023, the parties entered into a stipulation to postpone further proceedings until the end of the 2024 sports season. The NCAA agreed not to enforce its transfer rules in the interim.

On January 18, 2024, the United States (through the Justice Department), the District of Columbia, and the states of Mississippi, Minnesota, and Virginia intervened in the suit.

On January 31, 2024, the states of Tennessee and Virginia sued the NCAA under antitrust laws, claiming the NCAA’s NIL policies and “guidance” impermissibly prevent collectives representing schools in their states from discussing and negotiating NIL opportunities with high school and transfer portal prospects.

On February 23, 2024, the federal district court judge overseeing the case issued a preliminary injunction against the NCAA, prohibiting it from enforcing the NCAA’s NIL-related no-negotiation rule with respect to third parties such as boosters or collectives.

The ruling has been hailed in the media as a crucial move away from amateurism-based principles and regulation.

However, the ruling was very narrow.

The injunction does not disturb broad prohibitions on play for play (from any source) or pay for NIL by a university (rather than a third party) to induce an athlete to attend their institution.

The injunction applies only to NIL prohibitions that prevent “student-athletes from negotiating compensation for NIL with any third-party entity, including but not limited to boosters of a collective of boosters…” (emphasis added)

On March 1, 2024, NCAA President Charlie Baker sent a letter to member schools informing them that the Division I Board of Directors had instructed the NCAA enforcement staff to “pause and not begin investigations involving third-party participation in NIL-related activities.”

Importantly, the transfer and NIL suits were driven in whole or part by competitive advantage/disadvantage concerns in the talent acquisition market. Each suit sought to meet Power 5 schools' short-term labor needs.

While states in both suits wrapped their legal arguments around free markets and concerns for athletes’ rights, the relief they seek serves mainly institutional purposes to field successful, profitable football and men’s basketball teams.

In its motion for a preliminary injunction in the NIL suit, Tennessee argued that an NCAA infractions case against the University of Tennessee for alleged violations of NCAA’s NIL policies would harm the state’s “quasi-sovereign interest in the economic well-being of their residents in general.”

Tennessee also claimed the NIL recruiting ban “hinders recruiting and that schools accused of violating the ban lose players, scholarships, and post-season opportunities, which decreases competitiveness and fan interest” and that “no damages could replace players lost, reputations harmed, games not played, or championships not won.”

These are undeniably institutional interests that overshadow athlete interests.

Any benefit to athletes is purely incidental to that purpose and the product of temporary interest convergence.

Note: For an excellent analysis of interest convergence in college sports, see McCormick, Amy Christian & Robert A. McCormick, Race and Interest Convergence in NCAA Sports, 2 Wake Forest J.L. & Pol'y 17 (2012).

D. Deja Vu All Over Again: Congress, Congress, Congress

While the states in these two suits opportunistically challenge NCAA regulatory authority, the NCAA and Power 5 conferences in which these schools reside are actively lobbying Congress for protective federal legislation that could neutralize or eliminate the immediate recruiting benefits the schools seek in the lawsuits.

Since the Interim Policy, NCAA leaders, Power 5 conference commissioners, Power 5 university presidents, Power 5 athletic directors, and hall of fame Power 5 coaches have worn a path to Washington.

They’ve had ready access to lawmakers and influenced the course of debate in Congress.

Note: For a detailed discussion of the NCAA/Power 5 institutional (“grassroots”) lobbying campaign, see the “Lobbying” materials accessible from the homepage.

Congress has held five hearings in the last year, and six new bills (or “discussion drafts) have emerged. That’s a hearing every two-and-a-half months and a new bill every two months.

Bills introduced by Senators Roger Wicker (R-MS), Lindsey Graham (R-SC), Ted Cruz (R-TX), Tommy Tuberville (R-AL), Joe Manchin (D-WV), and House member Gus Bilirakis (R-FL) would roll back the current NIL and transfer markets and give substantial decision-making authority to the NCAA and Power 5 in a federalized athlete benefit marketplace.

Is it likely that institutional stakeholders at the universities of Tennessee, Ohio State, North Carolina, or Virginia, for example, will oppose protective federal legislation that would grant the NCAA and Power 5 unchallengeable authority to impose and enforce regressive prohibitions on NIL and transfer?

Are these universities going to demand that SEC, Big Ten, and ACC lobbyists immediately cease their lobbying activities in the name of athletes’ rights?

Are lawmakers from those states going to filibuster a bill like Wicker’s, Cruz’s, or Bilirakis’ because they run roughshod over athletes’ basic rights as Americans?

Time will tell, but if history is our guide, Power 5 schools in these states will fall in line and profess their unconditional support for a bill that grants preemption, antitrust immunity, and no-employee status for athletes.

They will do so in the name of preserving and protecting the “integrity” of college sports, creating a “level playing field” for schools, and promoting the “well-being of student-athletes.”

Moreover, as discussed above, if the NCAA and Power 4 reach a global settlement of House, Hubbard, and Carter, rest assured there will be a race to Congress for federal protections and immunities.

E. Values Vacuum

Any meaningful discussion about the values of college sports and higher education is lost in the confusing crosscurrents and short-term consequences of unregulated NIL and transfer markets.

College sports are ostensibly a values-based enterprise. Those values should be informed by the highest aspirations of higher education and intercollegiate athletic competition.

Universities exist to acquire and disseminate knowledge for the public good. The means to that noble end are rooted in evidence, not myths; critical analysis, not talking points; and open, robust, good-faith debate, not star-chamber self-dealing and decision-making.

The NCAA and Power 5 have lost sight of these fundamental features of American discourse in higher education and the broader marketplace of ideas.

Instead, our most powerful institutions of higher learning have succumbed to the desire to win at all costs, regardless of the consequences.

Their invocation of cynical, self-serving concepts like “amateurism,” “student-athlete,” and “collegiate model” is nothing more than a cover for a rapacious commercial industry that increasingly has little to do with education.

Moreover, when it comes to college sports, institutional beneficiaries of the status quo have created a climate and culture where differing viewpoints are treated with intolerance, suspicion, and disdain.

To understand the confusing events, narratives, and institutional forces driving the debate over the future of college sports, athletes and other stakeholders must be willing to break through artificial, self-serving barriers to robust, thoughtful debate.

F. A Path Forward for Athletes

Quotes from Albert Einstein and Barbara Tuchman suggest a way to recalibrate stakeholders’ thinking on the “problems” in college sports and bring the discussion back in alignment with the values of higher education, fundamental principles of economic freedom, and the interests of the very athletes the enterprise has pledged to protect.

Einstein said:

“If I had an hour to solve a problem, I'd spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.”

Einstein counsels that a proper, thorough analysis of the “problem” will lead to a quick, perhaps self-evident solution. It also implies the folly of solving a problem you haven’t appropriately framed or studied honestly.

An obvious precondition to any problem-solving is having complete, accurate, and reliable information relevant to the issue at hand.

The NCAA and Power take Einstein’s model and turn it upside down.

In their engagement with Congress and through their public lobbying campaign, the NCAA and Power 5 have spent 55 minutes propagandizing a pre-determined solution that protects their business interests and only 5 minutes even acknowledging the actual “problem,” which is their ongoing failure to promote and protect the interests of the athletes they claim to serve.

The NCAA and Power 5 substitute facts, data, and critical analysis with mythology and “tradition.”

Their starting point is self-interest and an abiding belief that they, and they alone, should occupy the Iron Throne of college sports regulation and be accountable to no one.

The NCAA and Power 5’s “my way or the highway” thinking lacks imagination and innovation.

Potential changes to the business model that acknowledge athletes’ actual value to the system have been quarantined within NCAA and Power 5-defined “guardrails” that make meaningful change all but impossible.

Tuchman’s quote—“Telling the truth about a given condition is absolutely requisite to any possibility of reforming it.”—captures the essence of the athletes’ dilemma.

No intelligent, effective change can occur if stakeholders are not honest and transparent about the “condition” they seek to change.

DYK is built around educating athletes and stakeholders on unreported or underreported aspects of the college sports enterprise.

We ask premise questions rather than accept as true mythology-based presuppositions about the regulatory and business models.

Knowledge is power, and we hope to inspire athletes to seek and use it aggressively.