III. How the NCAA Portrays Itself to the Outside World

This section provides basic information on how the NCAA defines and portrays its regulatory, governance, and enforcement structures to the outside world. The information in this Section comes exclusively from NCAA-published material.

The NCAA’s organizational self-portrait masks the true nature and purpose of the NCAA/Power 5 regulatory and governance models.

In assessing the NCAA’s self-described regulatory and governance structures and values, there are two important realities to bear in mind that you will not find in any of the NCAA’s published materials.

Power 5 Football Interests Dominate NCAA Policy and Governance While Basketball Money Funds the Entire NCAA Administrative State

The NCAA national office bureaucracy and the Football Bowl Subdivision members (“FBS”; Power 5/Group of 5 conferences/Notre Dame) are the most consequential components of the NCAA organizational structure.

This reality conflicts with the “big tent” governance model the NCAA pushes for public relations purposes, which conflates the interests of lower-level Division I, Division II, and Division III with Power 5 heavyweights.

FBS conferences and schools generate nearly all revenue in the overall college sports financial model.

Power 5 football revenue dwarfs all other revenue sources combined, and the gap is widening with billion-dollar-plus conference media rights deals, an expanded CFP, and new fan engagement markets and technologies.

FBS basketball is a distant second but of enormous institutional value to the NCAA because March Madness money underwrites the entire NCAA bureaucratic state.

From 1951 - 1981, the NCAA had an iron-fisted monopoly over televised football. In the Board of Regents antitrust litigation (1981 - 1984; discussed in the Timeline), the US Supreme Court struck down the NCAA’s football contracts and left the future of televised football to the free markets.

As a result, the NCAA receives no money from Power 5/FBS football (regular season, bowl games, or College Football Playoff).

The NCAA has nothing to do with Power 5 football beyond ministerial bowl certifications.

The NCAA’s sole source of revenue is the Division I men’s basketball tournament (March Madness). Men’s basketball funds all NCAA administrative expenses, including legal and lobbying costs from which Power 5 football benefits.

Since losing its football empire in 1984, the NCAA has aggressively and successfully marketed and promoted the March Madness tournament into one of the most popular and lucrative sports products in American history.

The NCAA’s first and longest-serving chief executive, Walter Byers (1951 - 1987), said in his 1995 book Unsportsmanlike Conduct: Exploiting College Athletes:

“The Division I men’s basketball tournament and its TV contract are the NCAA’s crown jewels. Tournament income, for practical purposes, finances the entire organization. As I was leaving office [in 1987], tournament gross receipts exceeded $70 million per year, with ticket sales accounting for around 13 percent and TV fees approximately 85 percent. For the 1993-94 fiscal year, NCAA total revenue was $182 million with TV rights fees, almost all related in one way or another to the basketball tournament, making up 78 percent. The tournament generates the TV largess that now is acknowledged to be the lifeblood of the organization.”

Byers, W., & Hammer, C. (1995, October 3). Unsportsmanlike Conduct: Exploiting College Athletes, p. 261.

The NCAA’s current TV contract with CBS and Turner (plus ticket sales) is worth $1 billion per year and extends into 2032. Barring a breakoff of Power 5 basketball from the NCAA, March Madness money essentially guarantees the perpetuation of the NCAA administrative state.

Power 5 football interests use March Madness money as nothing more than a bargaining chip to impose their will on the overall college sports marketplace and, importantly, over NCAA governance.

If Power 5 football broke away from the NCAA and took their basketball products with them, the NCAA would be reduced to a glorified high school athletic association.

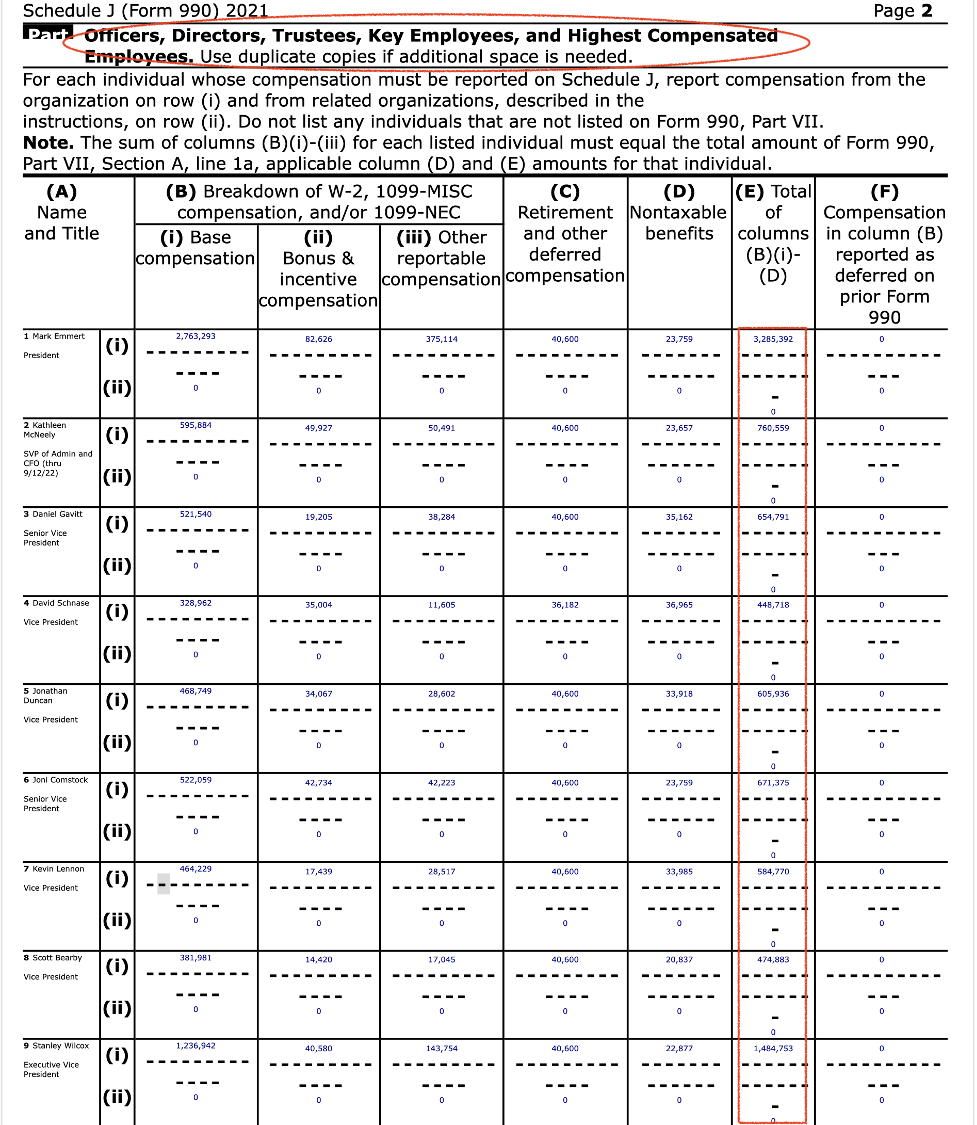

The NCAA executive class would have to say goodbye to their lavish salaries, which can exceed seven figures, and generous benefits packages, which include golden parachute payouts, private jets, and elaborate conferencing, wining, and dining with America’s rich and famous.

This dysfunctional regulatory detente is reinforced through March Madness distributions to stakeholders who contribute nothing to the NCAA’s bottom line.

Divisions II and III are largely irrelevant to the college sports regulatory and business models. No Division II or III products generate revenue, and their institutional representatives have only token seats in Association-wide governance.

Divisions II and III have governance bodies and committees that mimic Division I structurally but operate without meaningful scrutiny.

Both Divisions receive substantial block grants from March Madness money. Division II receives approximately $55 million each year, and Division III approximately $37 million.

The block grants are crucial to Division II and III finances and underwrite both bureaucracies. The NCAA and Power 5 football interests have used the block grant distributions to essentially purchase Division II and II loyalty and votes.

Divisions II and III (and lower-level Division I) have come to view their annual March Madness checks as non-negotiable entitlements.

In connection with the ratification of the new NCAA Constitution in January 2022, the NCAA and Power 5 emphasized the need to retain the Division II and III block grants to garner support.

As addressed in the Timeline, the new Constitution consolidated and strengthened Power 5 football’s regulatory and governance authorities under the NCAA umbrella.

Ratification required a two-thirds majority of all 1,100 NCAA schools. Division II and III combined gave the NCAA and Power 5 the votes they needed for passage.

Bob Gates, an independent member of the NCAA Board of Governors, former Director of the CIA, and former university president, served as the Chair of the NCAA Constitution Committee.

In an NCAA podcast interview in September 2021—before a draft of the new Constitution existed— Gates identified the Division II and III block grant distributions as “non-negotiable” items and necessary to gain Division II and III support for the new Constitution. (see video clip below)

In their congressional/lobbying campaigns for protective federal legislation, the NCAA and Power 5 have conflated the interests of Divisions II and III with those of the NCAA and Division I to suggest that any changes to college sports regulatory or business models (e.g., Power 5 athlete compensation, potential employee status, a meaningful athlete voice in decision-making) will harm Divisions II and III.

Star Chamber Decision-Making Within and Outside the NCAA Governance Structure Drives Policy and Rulemaking

The NCAA’s portrayal of its governance decision-making structures is misleading.

NCAA governance has evolved to protect only two things: (1) Power 5 football’s regulatory dominance and financial autonomy and (2) preservation of the NCAA administrative state. The NCAA, Power 5 conferences and institutional interests have gone to great lengths to mask these undeniable truths through bureaucratic and public relations sleight-of-hand.

A confusing array of boards, committees, subcommittees, task forces, working groups, and public relations misdirection obscures the current regulation, governance, and enforcement structures in college sports.

The NCAA and Power 5 repeatedly compare their existing governance model to “representative democracy” bodies in state and federal governments, suggesting that NCAA decision-makers operate within principles of elected representation, separation of powers, and checks and balances.

In-system stakeholders and leaders blame NCAA inaction and delay on faithful adherence to their claimed “democratic” processes and the “necessary” inefficiencies in them.

This is one of the grand illusions in college sports.

In reality, the most consequential decisions in college sports are made by a small group of influential Power 5 and NCAA insiders—promoting big-time football interests—who have little accountability to the members they claim to represent.

In formal NCAA governance structures, these select decision-makers skillfully manipulate the composition of boards and committees to retain iron-fisted control of the overall regulatory apparatus.

The color-coded screenshot image below illustrates the extent of cross-over representation among a small group of key decision-makers across NCAA and Division I boards, committees, subcommittees, task forces, and working groups central to NCAA governance.

Note: This image comes from DYK’s NCAA Governance Chart and shows (as of October 2022) the extensive involvement of a small number of decision-makers. The full Chart can be found in the Resources Tab in the Explore drop-down menu.

The NCAA President is not elected by the membership and does not have direct accountability or responsibility to the membership. The President is hired by the nine-member NCAA Board of Governors and reports only to the Board of Governors.

Similarly, members of the Board of Governors are not elected by the membership. Those seats are filled through a Divisional selection/nomination process often with preferred candidates.

Athletes are not members of the NCAA. They have token representation at some NCAA decision-making tables through an athlete committee structure that exists at the pleasure and under the control of the NCAA. Athletes have no independent right to demand a seat at decision-making tables and do not have direct, independent standing to challenge NCAA rules and eligibility decisions.

Perhaps more importantly, Power 5 football influences operate outside the formal governance structure through secret communications to shape the future of college sports to their liking (see “Power 5 Secret Society” Tab in the Explore menu).

This feature of Power 5 football-dominated secret discussions and decision-making is becoming more common as conference realignment, CFP expansion, and external regulatory forces (e.g., federal courts, administrative agencies, state legislatures) complicate the power conferences’ regulatory chess board.

Recently, the SEC and Big Ten further isolated their interests from the rest of college sports, and importantly, the Big 12 and ACC, by forming the “SEC-Big Ten Advisory Group.”

Big Ten Commissioner Tony Petitti and SEC Conference Commissioner Greg Sankey have been the face of the Advisory Group.

Petitti, Sankey, and Big Ten/SEC decision-makers created the Advisory Group before consulting the Big 12 and the ACC.

In response to criticism over the exclusion of the Big 12, ACC, and other stakeholders, Sankey said:

“Big problems are not solved in big rooms filled with people. You have to narrow the focus a bit. There may be raised eyebrows. We certainly called in advance to communicate what was going to be announced rather than do it in the shadows and have someone report on it. You might as well put things out there.”

That, in Sankey’s mind, is” transparency.”

The very existence of the Advisory Group is an affront to the NCAA’s self-described “representative democracy” because it operates entirely outside the NCAA governance process.

Yet, the NCAA is not up in arms as the SEC and Big Ten engage in a hostile takeover of the future of college sports.

I. NCAA and Divisional Self-Described Governance Structures and Stated Values

A. NCAA Association-Wide Governance

1. NCAA Membership

* 1,075 schools

* 500,000 athletes across three Divisions

* 97 conferences across all Divisions

* 24 “mainstream” sports with national championships across Divisions (., football, basketball, soccer, softball, field hockey, track, volleyball)

* 23 “other” sports across Divisions (e.g., bowling, sailing, squash, polo)

* 6 “emerging” sports across Divisions (eSports, women’s rugby, women’s wrestling)

2. NCAA Mission and Priorities:

(1) overall: “Provide a world-class athletics and academic experience for student-athletes that fosters lifelong well-being.” (2) rulemaking and enforcement, (3) generate revenue and increase fan engagement (NCAA 2023-2024 Division I Manual and NCAA 2021-2022 Form 990 nonprofit tax return)

3. NCAA Governance Structure Chart (NCAA 2023-2024 Division I Manual)

Note: The Association-wide governance structure conforms to the new NCAA Constitution ratified on January 22nd, 2022. The Board of Governors, which is the only Association-wide governing body, was cut from 21 voting members to nine and, for the first time, included one Division I conference commissioner and one athlete as voting members; the new Constitution emphasized Divisional authorities and curtailed role of Board of Governors

4. NCAA Revenue and Select Expenses (NCAA Form 990 tax return [2021], “Where Does the Money Go?” [2021], “Did You Know?” [2020 NCAA website])

Reminder Note: Because of the 1984 Board of Regents Supreme Court ruling (discussed in the Timeline), the NCAA receives no money from Power 5/FBS football (regular season, bowl games, or College Football Playoff).

5. Infractions and Enforcement (NCAA website 2023 under “NCAA” Tab, NCAA Division I Infractions 2021-22 Annual Report); cases disproportionately weighted to football and men’s basketball

B. Division I

There are essentially four categories (in hierarchical order of importance at the regulatory and financial levels):

(1) Power 5 “Autonomy” Conferences (approx. 65 schools from ACC, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12, SEC, and Notre Dame)

(2) Football Bowl Subdivision (“FBS”; 10 big-time football conferences and 130 schools, including the Power 5 and Group of 5 plus Notre Dame; all FBS conferences and schools are eligible for the College Football Playoff)

(3) Football Championship Subdivision (“FCS”; 14 conferences and approx. 135 schools; FCS football is less competitive, ineligible for the CFP and major bowls, and includes, for example, the Ivy League)

(4) non-football conferences and schools; emphasis is basketball-oriented (approx. 100 schools)

1. Membership (approximate)

* 350 schools

* 32 conferences

* 190,000 athletes

* mostly large public schools

* subdivisions “based on football sponsorship”

* offers full athletic scholarships

* FBS schools must sponsor at least 16 sports

* the rest of Division I must sponsor at least 14 sports

2. Division I Mission/Priorities (NCAA website 2023)

Note that the first Division I Priority is a “Commitment to Amateurism”

3. Governance/Legislation Structure Charts (NCAA 2023-2024 Division I Manual); post-Autonomy classification [2014] and new NCAA Constitution [January 22, 2022])

C. Division II

1. Membership (approximate)

* 300 schools

* 23 conferences

* 125,000 athletes

* based on a partial scholarship model

* mix of public/private schools

* approximately 170 schools offer football

* schools must sponsor at least 10 sports

2. Division II Mission/Priorities

3. Division II Governance Structure and Financing

The Division II governance structure largely mimics Division I.

Division II receives a $55 million block grant each year from NCAA March Madness revenues. The March Madness payout funds the entire Division II administrative state. Additionally, Division II receives free Association-wide benefits valued at $250 million, all paid from March Madness money.

Beyond nominal membership dues per institution, Division II generates no revenue for the NCAA.

Note: The Division II Manual closely tracks the Division I Manual and includes the NCAA Constitution, conduct standards, and amateurism-based financial aid/recruiting/eligibility rules.

D. Division III

1. Membership (approximate)

* 440 schools

* 40 conferences

* 195,000 athletes

* does not award athletic scholarships

* 80% of schools are private many with very small enrollment

* schools with less than 1,000 students must sponsor at least 5 men’s and 5 women’s sports; schools with more than 1,000 students must sponsor at least 6 men’s sports and 6 women’s sports

2. Division III Mission/Priorities

3. Division III Governance Structure and Financing

The Division III governance structure largely mimics Divisions I and II.

Division III receives a $37 million block grant each year from NCAA March Madness revenues. The March Madness payout funds the entire Division III administrative state. Additionally, Division III receives free Association-wide benefits valued at $250 million, all paid from March Madness money.

Beyond nominal membership dues per institution, Division III generates no revenue for the NCAA.

Note: The Division III Manual closely tracks the Division I and II Manuals and includes the NCAA Constitution, conduct standards, and amateurism-based financial aid/recruiting/eligibility rules.