III. Labor Protections

Agency action on labor issues strikes at the heart of the legal relationship between athletes and institutions and the concept of the “student-athlete.” The central threshold question in determining the role of federal labor agencies is whether athletes—or certain classes of them—are employees of their university. Without employee status, federal labor-oriented agency action is substantially curtailed or eliminated.

A. National Labor Relations Board (NLRB)

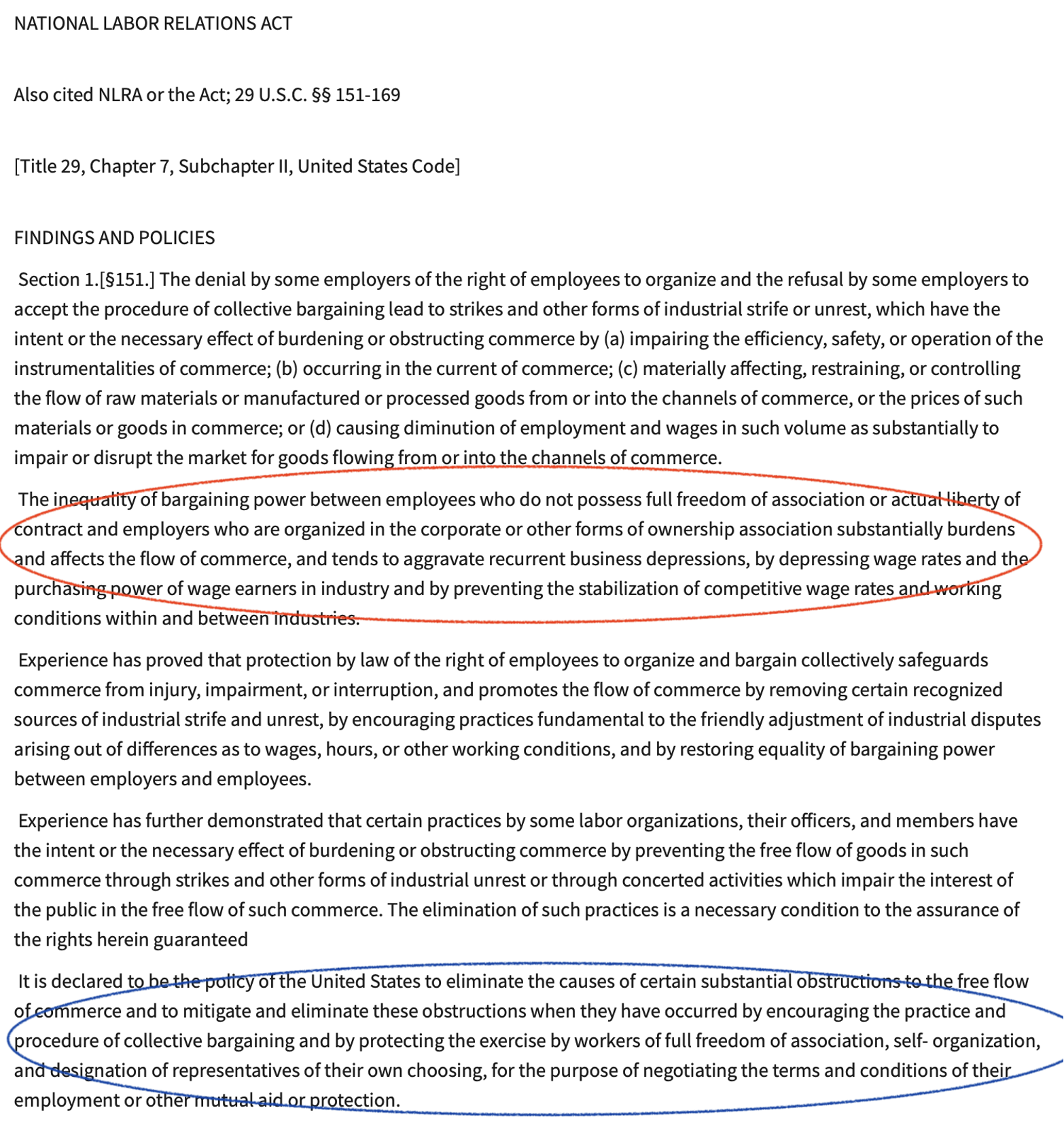

The NLRB interprets and enforces the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), America’s seminal labor rights law. The NLRA is an expansive law that provides workplace protections for employees including, (1) work terms and conditions, (2) employee representation/voice through unionization and collective bargaining, and (3) compensation.

Note: For a discussion of the history, mission, and role of the NLRA/NLRB and their connection to college sports, see the DYK Podcast interview with NLRB Deputy General Counsel Peter Ohr. Mr. Ohr authored the NLRB decision in the Northwestern unionization case in 2014 (see below) and now serves as the NLRB’s number two lawyer under General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo.

Importantly, the NLRA is premised on fundamental American values. Section 1 of the NLRA speaks in terms of freedom of association, freedom of contract, and democratic representation in the workplace.

Employees have the right to self-organize through collective action, including forming a union (Section 7) through a “petition” process. Employees may also seek redress for specified unfair labor practices (Section 8) through a “charge” process.

The NLRA applies only to private employers. This creates jurisdictional/coverage issues in college sports cases because most schools at the highest levels of play (Power 5 conferences) are public.

As discussed below, in the USC charge filed in February 2022, athletes contend the Pac-12 conference and the NCAA are “joint employers” which may bring public schools under the coverage of the NLRA.

The NLRB has asserted jurisdiction in several college sports-related cases that have been brought to the Board for review. They fall into two categories: (1) unionization and (2) substantive violations of the NLRA.

1. Unionization

Northwestern Football (2014)

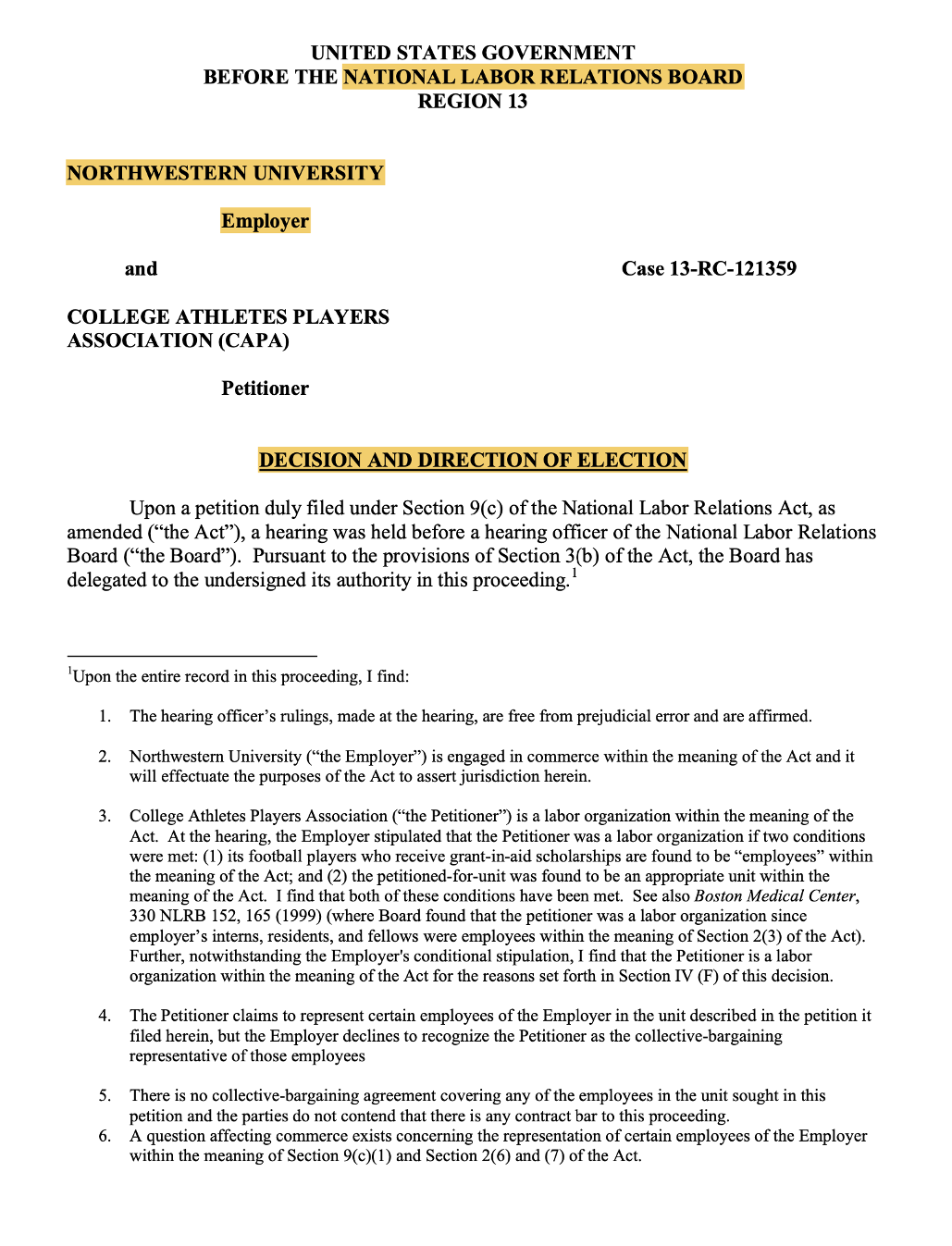

In 2014, the Northwestern University football team (a private school and member of the Big Ten Conference) filed a petition with the NLRB to form a union. However, the players first had to establish that they were employees of Northwestern.

After gathering evidence on the employee issue and conducting a hearing spanning several weeks, the hearing officer and Regional Director (Peter Ohr) determined, as a matter of fact, that the Northwestern football players on scholarship met the well-established common law test for employee status and were entitled to vote on whether to form a union.

Northwestern (and the NCAA through a friend of the court brief) argued that the players were “student-athletes” who could not be employees. Essentially, Northwestern argued that “student-athlete” is the legal opposite of employee, and athletes could not be both. The Regional Director rejected that argument.

Northwestern appealed the decision to the National Board, which declined to assert jurisdiction, basically punting on the issues raised in the petition. The Board relied in large part on the private-public coverage issue.

Of the sixty-five schools then in the Power 5 conferences, only twelve—including Northwestern—are private. The Board was concerned that having only a small subset of Power 5 schools eligible for NLRA union status would create regulatory confusion and would “not promote stability in labor relations.”

However, the Board made clear that its decision to decline jurisdiction applied only to the Northwestern football team and did not exclude the possibility of a different outcome under different circumstances.

Significantly, the Board did not disturb the factual findings on employee status.

The Regional Director directed an election by the football players on whether to form a union. A vote took place, but the ballots were impounded pending Northwestern’s appeal to the National Board.

Because the National Board declined jurisdiction, the ballots were never counted and the outcome of the vote is unknown.

The Northwestern case has become a footnote in college sports regulatory history, but it is one of the most significant milestones in defining the legal relationship between athletes and institutions.

Essentially, the concept of the “student-athlete” had its day in court, and it lost.

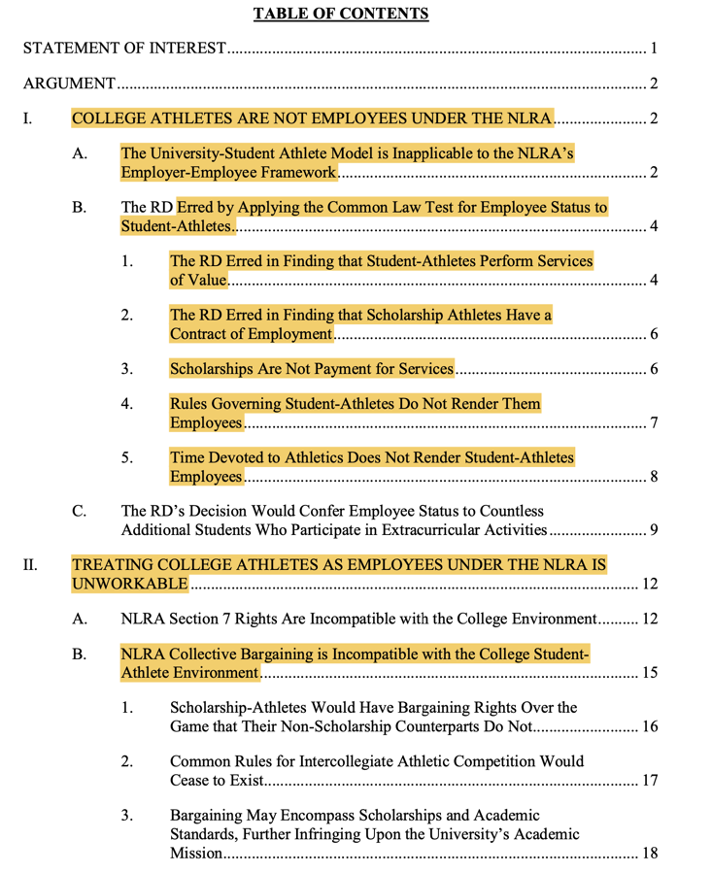

At the National Board level, nonparties opposing employee status flooded the docket with “friend of the court” briefs, including the NCAA, Big Ten, major universities, and education-oriented advocacy groups (e.g., the American Council on Education and the Association of American Universities).

One friend of the court brief of note was filed by members of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee and the House Committee on Education and the Workforce.

Senators Lamar Alexander (R-TN), Richard Burr (R-NC), Johnny Isakson (R-NC) and Reps. John Kline (R-MN), Virginia Foxx (R-NC), and Phil Roe (R-TN) opposed employee status for athletes, leaning into the mythical “student-athlete” concept.

No Democrats signed onto the brief.

The congress members summarily dismissed every finding by the Regional Director and claimed that employee status for Power 5 scholarship football players was an existential threat to college sports.

The brief demonstrated opposition to any discussion on whether athletes are, in fact, employees. Instead, the brief presented the issues through the lens of whether athletes should be employees.

This reflects the NCAA/Power 5 “my way or the highway” approach to athletes’ rights and employee status for Power 5 football and men’s basketball players.

Alexander and Burr’s participation in the NLRB brief was of particular importance because both played crucial roles in the NCAA and Power 5’s campaign in the Senate in the summer of 2020.

Alexander and Burr led the charge on federal legislation that would prohibit athletes from being employees of their university.

On September 15th, 2020, Alexander—as the Chair of the Health Education Labor and Pensions Committee (HELP)—held a hearing titled “Compensating College Athletes: Examining the Potential Impact on Athletes and Employees.”

In a free-form opening speech, Alexander made clear his opposition to athletes receiving any compensation, including for their name, image, and likeness, or being classified as employees, saying, “[t]he question for the hearing today is whether the tradition of the intercollegiate student-athlete is worth preserving.”

Alexander invoked the Knight Commission’s 1991 Report “Keeping Faith With the Student Athlete” saying, “I hope those words from the Knight Commission 30 years ago will guide how this Congress deals with the newest issues threatening the concept of student-athletes: allowing commercial interests to pay athletes for the use of their name, image, and likeness.”

Alexander also wanted any federal legislation to keep the NCAA in charge rather than turn over the regulation of college sports to a federal agency.

Alexander claimed to support NIL opportunities but made clear his belief that revenue-producing athletes should not be permitted to keep their money.

Instead, Alexander said that NIL earnings should benefit all student-athletes.

Burr, also on the HELP Committee, weighed in with equal disdain for athletes’ economic rights.

The 2014 brief with the NLRB and the 2020 HELP hearing are important case studies in the resilience of the no-employee line the NCAA, Power 5, and their allies in Congress have been defending since the 1950s.

New NCAA President Charlie Baker, Power 5 conference commissioners, athletics directors, high-profile coaches, many members of Congress, and the best lobbyists that athletes’ money can buy have assumed the mantle on the no-employee issue.

In 2024, the NCAA and Power 5’s arguments and tactical approach to their no-employee campaign are the same as in 2014 and 2020.

Note: The Regional Director’s opinion, hearing transcripts, the National Board’s opinion, and friend of the court briefs are available in the Resources Tab of the Explore menu on the Homepage.

Dartmouth Basketball (September 2023)

On September 13th, 2023, the Dartmouth College men’s basketball team filed a petition with the NLRB’s Boston office to form a union.

The case has moved quickly through the process.

On February 5, 2024, the NLRB Regional Director ruled in favor of the players and issued her Decision and Direction of Election.

Applying the common law test for employee status, the Regional Director found the athletes were employees within the meaning of the NLRA.

On March 5, 2024, the Dartmouth players voted 13-2 to form a union.

The case is on appeal to the National Board.

The appeals process could extend well into 2025 and perhaps 2026. Assuming Dartmouth obtains a stay of athlete union activity pending the appeals, any potential collective bargaining is far off.

The significance of the Dartmouth vote is difficult to assess. Because Dartmouth operates largely in private school space, some of the public-private concerns raised in Northwestern are less of an issue.

Moreover, there is precedent at Dartmouth for student worker unionization.

Dining hall student workers recently unionized to address work conditions and compensation. They bargained for more control over their schedules and increased their hourly wages (to $20 per hour).

These are modest improvements that haven’t caused disruptions to Dartmouth’s normal operations.

If the men’s basketball players ultimately achieve something similar, will it substantially impact Dartmouth or motivate other similarly situated athletes at other schools to petition for a union?

Will other Ivy League basketball teams follow suit?

Will the Dartmouth decision lead Power 4 athletes—particularly profit athletes—to petition the NLRB for employee status and the formation of unions?

The pending USC NLRB case (discussed below) does not raise that issue.

Are Power 4 athletes in football and men’s/women’s basketball content with their current NIL and transfer freedoms and ambivalent on employee status and unionization? Maybe they don’t want to rock the boat right now.

Whatever the thinking may be among these stakeholders, the Dartmouth case has not yet produced a “domino effect” since it was first filed in September 2023.

There are also political considerations in assessing the impact of the Dartmouth union.

The NLRB is an executive branch entity.

If we have a Republican president after the 2024 elections, the NLRB’s position on athletes as employees is very likely to change and become more aligned with NCAA/Power 5 thinking.

Another issue that may present itself if Power 4 profit athletes seek employee status and unionization is the difference between high-level, high-profit sports in the Power 5 landscape and lower-level Division I, Division II, and Division III sports.

The Northwestern ruling applied specifically to scholarship athletes in a Power 5 product. Similarly, the Abruzzo memo addressed certain athletes in big-money sports, following the ruling and logic in Northwestern.

Does it make sense in the context of employee status for Dartmouth men’s basketball to be on the same legal footing with Power 5 football and Power 5 men’s/women’s basketball?

Does the Dartmouth case further the interests of college athletes in Power 5 football and basketball who clearly meet the common law definition of employee, or does it obscure their interests?

As discussed in the Federal Courts Tab, a similar issue is presented in the Johnson v NCAA suit under the Fair Labor Standards Act.

These are questions that are likely to influence the appeals process.

With so many variables and interest groups operating in an unstable regulatory environment, it is impossible to predict what may come from the Dartmouth case.

But one thing appears certain.

The NCAA and Power 5 will use the Dartmouth case to double down on their no-employee campaign in Congress.

The NCAA’s “statement” on the Dartmouth union vote did precisely that.

“The NCAA is making changes to deliver more benefits to student-athletes, including guaranteed health care and guaranteed scholarships, but the NCAA and student-athlete leadership from all three divisions agree college athletes should not be forced into an employment model. The Association believes change in college sports is long overdue and is pursuing significant reforms. However, there are some issues the NCAA cannot address alone, and the Association looks forward to working with Congress to make needed changes in the best interest of all student-athletes.”

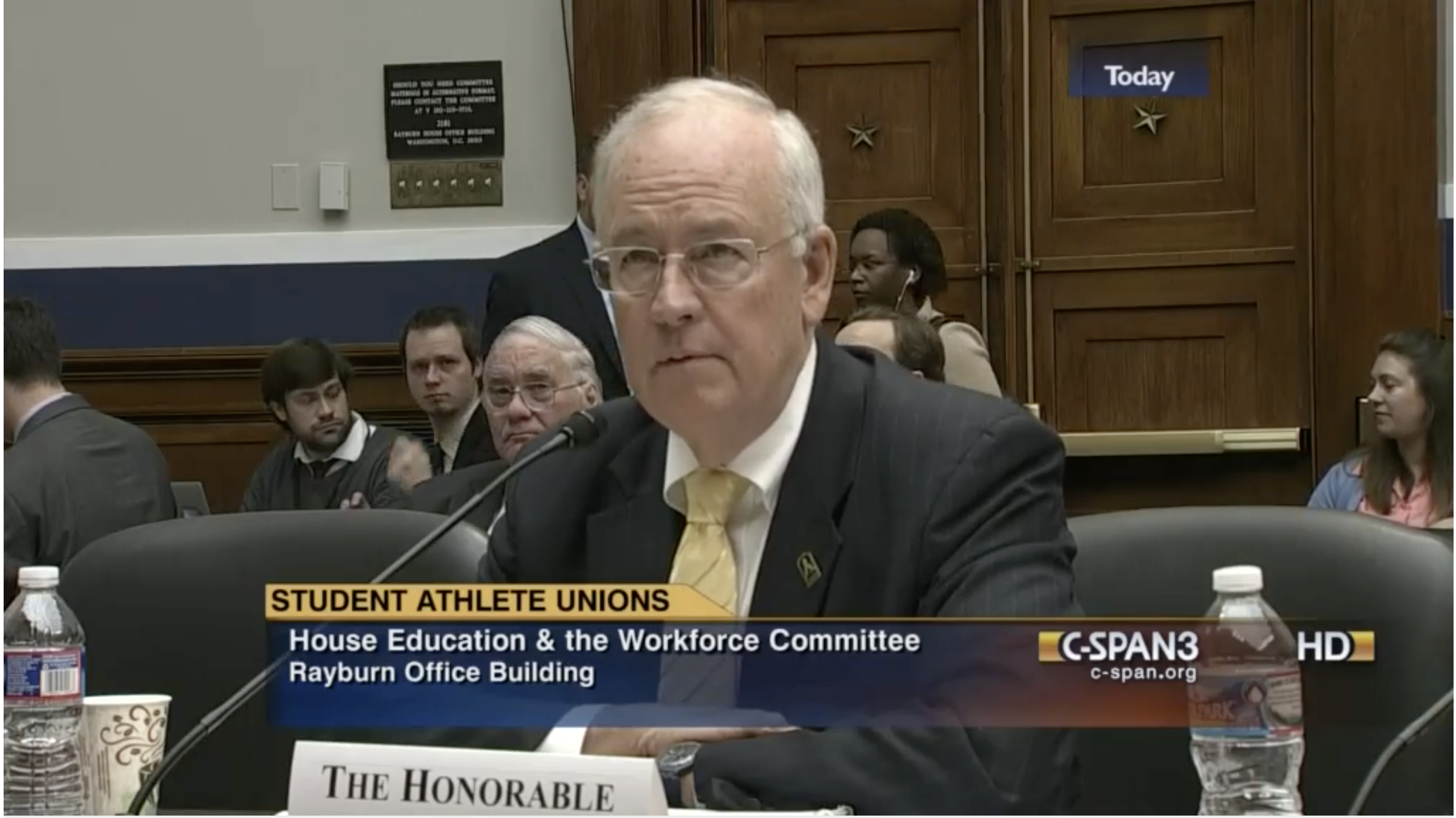

Additionally, on the same day as the vote to unionize, the House Committee on Education & the Workforce’s Subcommittees on Health, Employment, Labor, and Pensions and Higher Education and Workforce Development announced a March 12th hearing titled (ironically) "Safeguarding Student-Athletes From NLRB Misclassification.”

The March 12, 2024 hearing was identical in context and purpose to a reactionary hearing in the same committee on May 8, 2014, after the regional director issued his decision in the Northwestern case.

The 2014 hearing was likewise ironically titled “Student-Athlete Unions.”

Murphy-Sanders College Athlete Right to Organize Act

In May 2021, Senators Chris Murphy (D-CT) and Bernie Sanders (I-VT) introduced the College Athlete Right to Organize Act (CAROA), which would amend the NLRA to define college athletes receiving direct compensation from their university that requires participation in athletics as employees.

The bill would also amend the NLRA to define public universities as employers for purposes of college sports and permit collective bargaining.

CAROA invokes Congress’ constitutional powers to regulate commerce and appears to override state labor laws.

The bill applies to institutions and conferences but not the NCAA.

Additionally, CAROA excludes athletic scholarships from income for tax purposes.

CAROA would theoretically solve the NLRB’s public-private jurisdictional issues and presumably any conflict between the NLRA and state labor laws.

On December 6, 2023, Murphy and Sanders rereleased CAROA. The rerelease coincided with the CFP selection weekend and NCAA President Charlie Baker’s announcement of his “D-I Project.”

Murphy’s press release said, in part:

“All the breathless attention on this weekend’s College Football Playoff selection is a reminder that college sports are anything but amateur. There is no college sports industry and its $16 billion in annual revenues without the athletes' labor. It’s past time they get a seat at the negotiating table. Instead of fighting athletes' rights in courts and spending millions on lobbying Congress, the NCAA and its members should start negotiating directly with players on revenue-sharing, health and safety protections, and more. This legislation would make it easier for the athletes to realize their power, form unions, and start to collectively bargain.”

CAROA has received little attention in the congressional debate.

2. Substantive Violations

The Abruzzo Memo: “Misclassification” and “Joint Employer” (September 2021)

On September 29, 2021, NLRB General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo issued a Policy Memorandum titled “Statutory Rights of Players at Academic Institutions (Student-Athletes) Under the National Labor Relations Act.”

Abruzzo’s memo followed the U.S. Supreme Court’s unanimous ruling in NCAA v Alston (June 21st, 2021), in which the Court held that the NCAA and Power 5 were not entitled to amateurism-based, judicially created antitrust immunity.

The memo took aim at the NCAA’s use and conceptualization of the term “student-athlete.” Noting that the NCAA (and former NCAA executive director Walter Byers) invented the phrase in the 1950s to avoid workers’ compensation liability, Abruzzo refused to use it. She alleged that using the phrase “student-athlete” was a “misclassification” of athletes and an independent violation of the NLRA because it led athletes to believe they had no protectable labor rights as employees under the NLRA.

Abruzzo also addressed the public-private school coverage issue under the NLRA. She took the position that because of the extent of control the NCAA exerted (through its rules) on the work conditions of athletes, it could be held liable under the NLRA as a “joint employer” with the universities. This would theoretically solve the public-private issue because the NCAA is a private entity within the scope of NLRA jurisdiction.

In December 2023, the NLRB published a Final Rule addressing the standard for joint employer status. The Board restored a more lenient standard from a 2018 NLRB case—Browning-Ferris—that emphasized the extent of control (including “indirect” control) the putative employer exercises over the employee.

USC/Pac-12/NCAA Misclassification and Joint Employer Charge

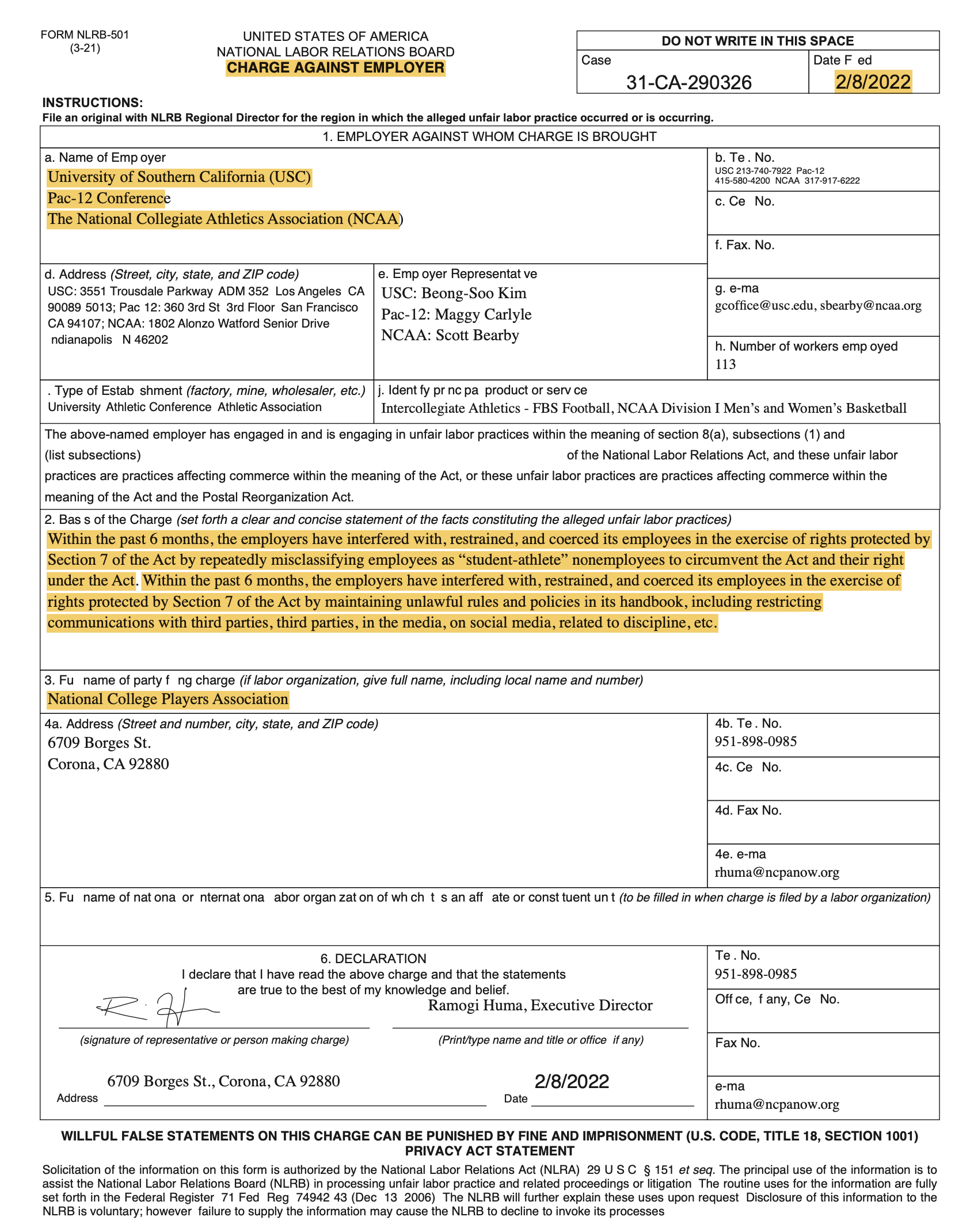

On February 8th, 2022, the National College Players Association—an athletes’ rights advocacy organization—filed a “charge” in the Los Angeles NLRB office against USC, UCLA, the Pac-12, and the NCAA. The charge alleged a violation of Section 8 of the NLRA for “misclassification” and also alleged the Pac-12 and NCAA were “joint employers” with the schools.

The case is not a petition to unionize.

The Regional Director in Los Angeles allowed the charge to proceed against USC (private school), the Pac-12 (what’s left), and the NCAA. The case is unlikely to be resolved until 2025 or 2026. It could conceivably wind up in the U.S. Supreme Court.

B. U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division

The Wage and Hour Division “enforces federal wage, overtime pay, recordkeeping, and child labor requirements” of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA).

Only employees are eligible for FLSA protections.

The FLSA is very different from the NLRA. It is a payment law that does not address work conditions, employee representation, or compensation issues outside of hourly workers (the FLSA does not apply to salaried workers).

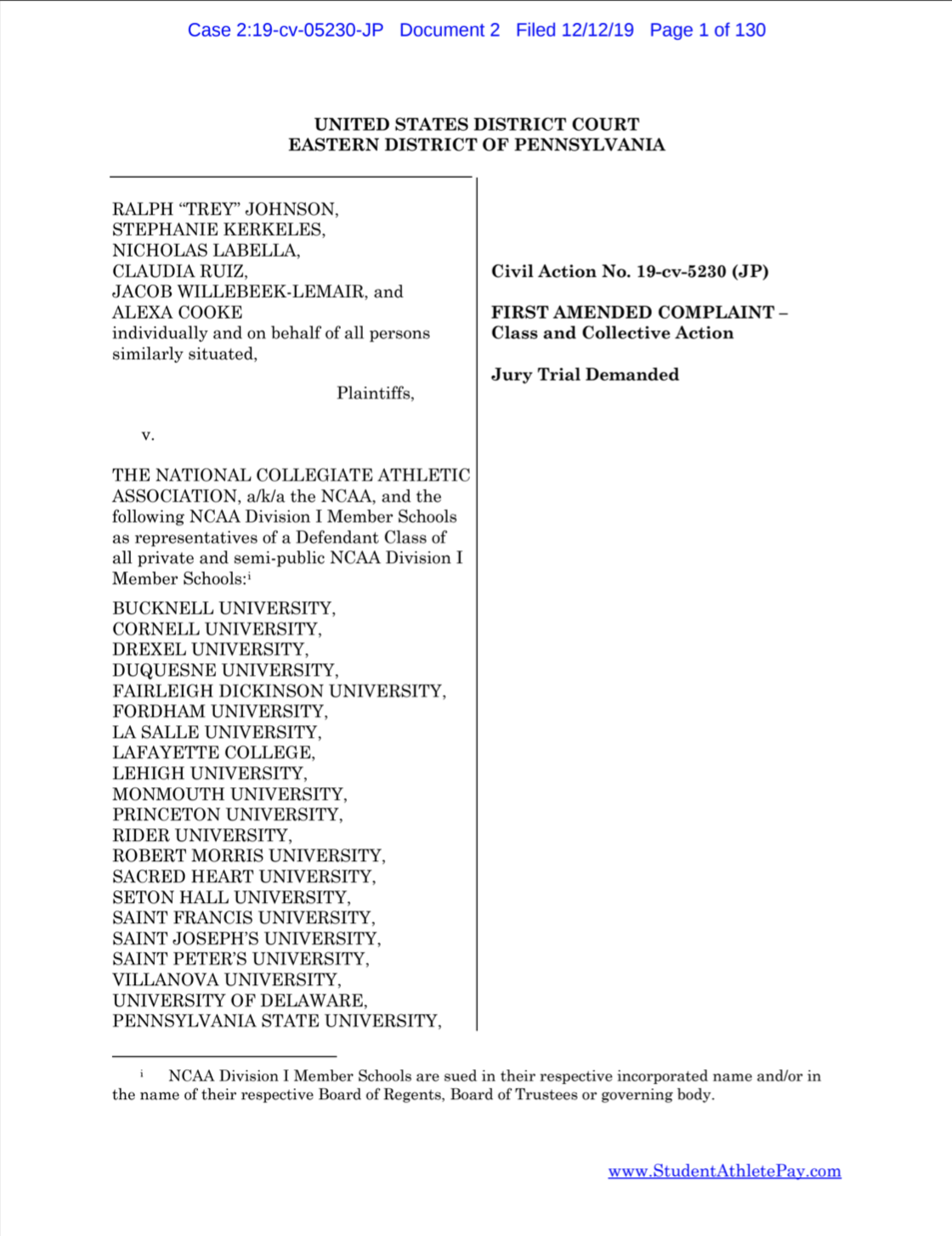

Johnson v NCAA (pending)

The Wage and Hour Division could be relevant and consequential in college sports because of the Johnson v NCAA case currently pending in the federal 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals.

Johnson seeks hourly wage benefits for athletes under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). The suit names several Division I universities (non-Power 5) and the NCAA. The athletes claim the NCAA is a “joint employer” with the universities. If the NCAA is deemed a joint employer, it could be responsible under the Act.

The NCAA and universities filed motions to dismiss, arguing that athletes cannot, as a matter of law, be employees under the FLSA.

The NCAA wants the case dismissed without any fact-finding under the various fact-intensive tests used to determine employee status under the FLSA.

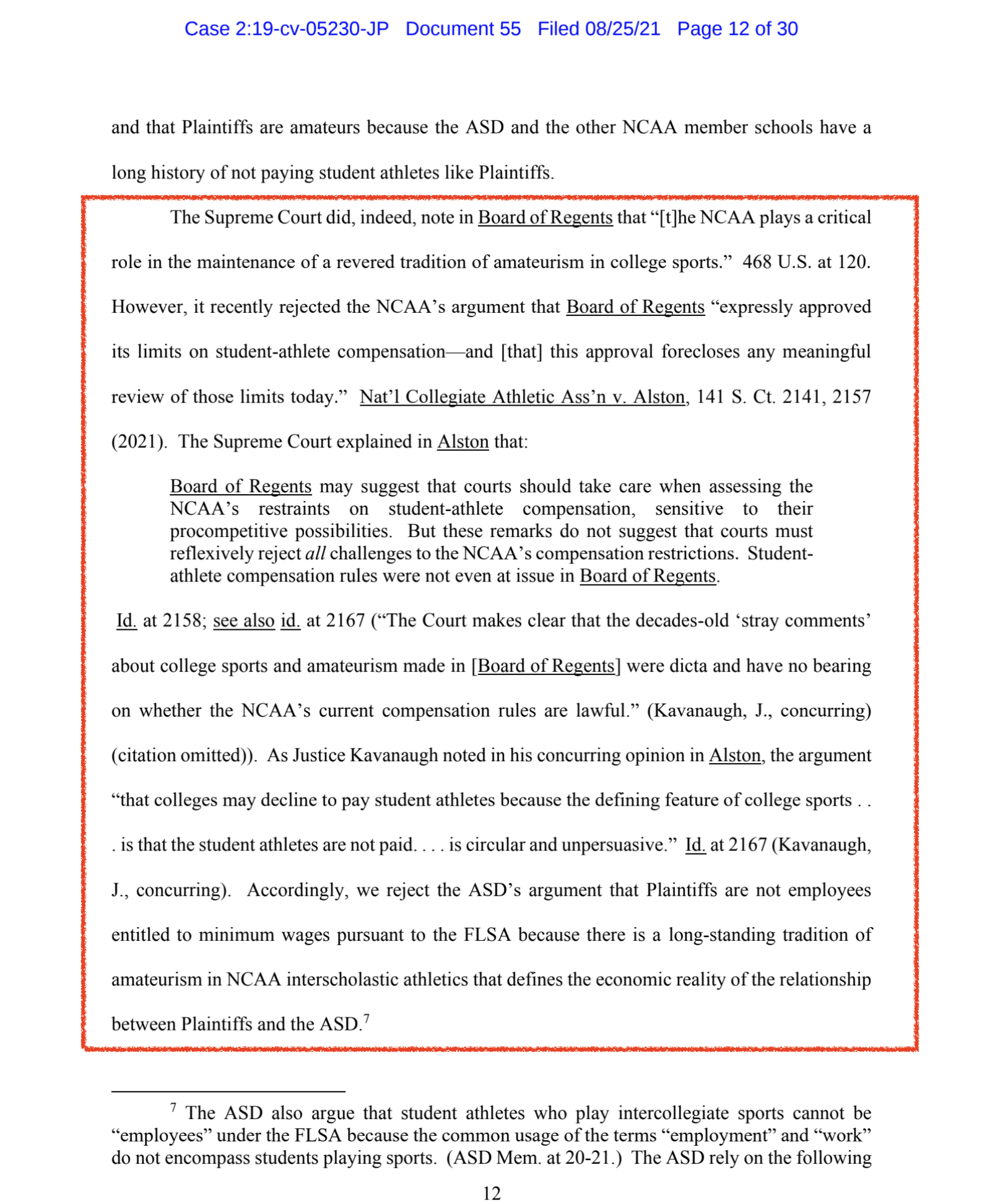

In support of its immunity argument, the NCAA relies mainly on a case from the Seventh Circuit, Berger v NCAA (2016),

In Berger, lower-level Division I athletes (women’s track athletes at the University of Pennsylvania) sought hourly wages under the Fair Labor Standards Act. The athletes had to first prove they were employees within the meaning of the Act.

Comparing athlete labor to prison labor, the court rejected, as a matter of law, the possibility that athletes could be employees. The court manufactured out of whole cloth an immunity shield for the NCAA from Board of Regents’ magic dicta:

“The Supreme Court [citing Board of Regents] has recognized that here exists in this country a ‘revered tradition of amateurism in college sports,’ a fact that cannot be reasonably disputed. That tradition is an essential part of the ‘economic reality’ of the relationship between the [athletes] and Penn. So, too, is the fact that generations of Penn students have vied for the opportunity to be part of that revered tradition with no thought of any compensation.” (emphasis added)

In September 2022, the district court in Johnson issued opinions denying the motions to dismiss on both the Berger immunity shield (employee status) and the joint employer theory. The court held that the case could proceed to the fact-finding stage on both issues.

On employee status, the court rejected the NCAA’s argument that it was entitled to an amateurism-based, judicially created immunity based on the off-hand language from Board of Regents.

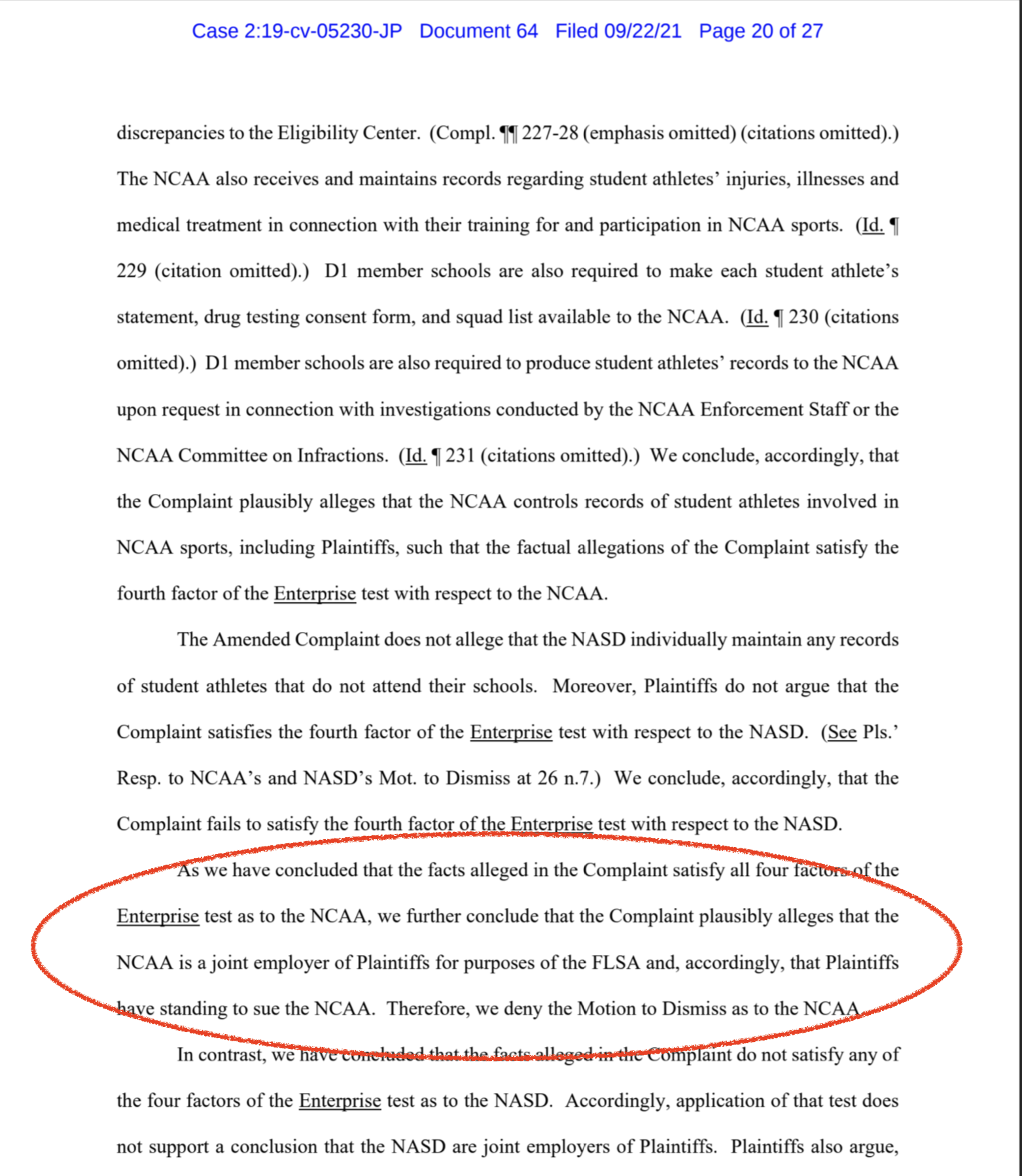

On joint employer status, the court held that the athletes’ complaint plausibly alleged that the NCAA was a joint employer with some schools, applying a four-part test for joint employer liability.

The NCAA then filed a rare emergency appeal (“interlocutory appeal”) to the Third Circuit, asking it to rule on the employee issue as a matter of law and grant the NCAA immunity from responsibility under the FLSA.

On February 15th, 2023, the Third Circuit held oral arguments. The three-judge panel was quite skeptical of the NCAA’s amateurism-based immunity arguments and suggested they were inclined to keep the case alive and send it back to the district court for fact-finding on the employee issue.

It’s important to note that a “victory” for the athletes at this stage of the litigation is merely having the opportunity to litigate the employee and joint employer issues in the ordinary course of civil litigation through “discovery.”

As with the other immunity shield cases, the athletes are simply trying to overcome the NCAA’s formidable amateurism-based immunity firewall to have a chance at a favorable outcome.

Johnson, like House, is a remote threat to the NCAA from a timing standpoint. If the Third Circuit keeps the case alive and sends it back to the district court for fact-finding, the litigation timeline (including appeals) could extend well into 2025.

This takes the timeline for both cases beyond the 2024 elections. If the Republicans take control of both chambers of Congress, the NCAA’s and Power 5’s campaign for protective federal legislation will receive a substantial boost.

If the 3rd Circuit allows the case to go forward and the athletes ultimately prevail, the Wage and Hour Division would have administrative jurisdiction.

Note: For a more detailed discussion of Johnson and the role of federal courts in college sports, see the Federal Courts Tab in the Explore menu on the Homepage

C. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)

The EEOC enforces federal civil rights laws in the employment context. Employee status is a prerequisite to EEOC jurisdiction.

In September 2022, the National College Players Association—as part of its “kitchen sink” approach—filed a complaint with the EEOC on behalf of black athletes in big-time sports products, claiming the NCAA’s amateurism-based compensation limits have a disproportionate impact on black athletes in violation of civil rights laws.

The EEOC has not acted on the complaint.

D. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)

OSHA is part of the U.S. Department of Labor. It is tasked to ensure safe and healthy working conditions by setting and enforcing federal standards. OSHA covers most private-sector employers and some public employers.

OSHA applies only to the employment setting.

Athletes receive some OSHA protections by association. Athletes use many facilities within OHSA’s coverage because university employees use those facilities. However, safety issues specific to athletes, like training equipment, athlete-specific facilities, and training protocols, may be outside OSHA’s jurisdiction.

E. The NCAA and Power 5’s Anti-Employee Campaign in Congress

As discussed above, a central component of the NCAA and Power 5’s campaign in Congress is to make it impossible for athletes to be employees of their universities.

In a September 14, 2023, podcast interview, outgoing Ohio State athletics director Gene Smith—an NCAA/Power 5 insider of the highest order—said that a federal law prohibiting athletes from being employees is the “Holy Grail” of the NCAA and Power 5’s congressional agenda.

Employee status for athletes, or some classes of athletes, is a crucial concern for the future of college sports. It raises complicated legal, regulatory, equity, and practical issues and requires thorough analysis and expert input.

Through twelve congressional hearings and sixty-two witness slots (see DYK diagram below; pro-NCAA/P5 witnesses in gold; pro-athlete witnesses in blue), not a single representative from the NLRB, the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division, the EEOC, or OSHA has testified.

At the March 12, 2024, hearing in the House Education & the Workforce’s Subcommittee on Health, Employment, Labor, and Pensions, former NLRB board member Mark Gaston Pearce offered compelling testimony on the history of the term “student-athlete” and the civil rights implications of the no-employee campaign. However, he made clear that he was not speaking for the NLRB or any other federal agency.

Given the policy implications of a federal law that would forever prohibit athletes from having protectable labor rights, it is crucial that agency experts have their turn behind the microphone to inform the debate.

Instead, the hearings have been dominated by NCAA/Power 5 insiders. They have preached NCAA mythology framed around the concept of the “student-athlete” rather than looking to facts and expert testimony.

Stacked witness lists, misleading testimony, and manipulation of the “athlete voice” have led crucial decision-makers to believe there is an absolute consensus that athletes shouldn’t be (and don’t want to be) employees (see video clip below of NCAA President Charlie Baker’s testimony at the October 17th, 2023 hearing in the Senate Judiciary Committee and Senator Ted Cruz’s [R-TX] questions and comments).

This false consensus tactic is central to the NCAA and Power 5’s broader congressional and public relations strategies and appears to have gained some traction in Congress.

Note that both Baker and Cruz cynically invoke the interests (and claimed opposition to employee status) of HBCUs and the NCAA Student Athlete Advisory Committee—a committee that exists at the pleasure of the NCAA and is controlled by the NCAA—to strengthen their consensus arguments.

Baker and Cruz leave the impression that there is not a single institutional stakeholder or college athlete who believes athletes are, or should be, employees of their university.

Baker’s use of Augustana University athletes as a surrogate for the voice of all athletes on the employee issue is profoundly misleading.

Augustana is a private Division II school in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Its undergraduate student population (1,900) is smaller than many public high schools.

Its athlete population is overwhelmingly white.

It is unlikely that Augustana athletes have an experiential understanding of what it is like to be a Power 5 profit athlete.

Yet Baker rattled off his talking points, including the “consensus” view of Augustana athletes on employee status, without any pushback.

If Baker held a similar forum at the universities of Michigan, Texas, Florida, or Washington for football and basketball players, is it likely that not a single athlete would support employee status?

Moreover, the invocation of HBCUs to support the NCAA/Power 5 no-employee ask is a head-spinning irony. The no-employee provision is specifically targeted to profit athletes in Power 5 football and men’s/women/s basketball, a substantial majority of whom are African American.

Importantly, this extraordinary limitation on athletes’ rights as Americans has nothing to do with the ostensible purpose of federal legislation, which is to provide NIL “compensation” for athletes. In the NIL market as currently structured (governed by state laws, state executive orders, or the NCAA’s “Interim Policy”), athletes can only enter NIL deals with third parties, not their universities.

This universal restriction makes it impossible for a NIL deal to raise legitimate employee issues.

Baker’s vaguely defined “D-I Project” proposal suggests that universities may be able to pay athletes directly for NIL, but as the market stands now, universities are prohibited from doing so.

It took over a year of hearings before a Congressmember called out the NCAA and Power 5’s bait and switch on their “no employee” ask. At the June 9th, 2021, hearing in Senate Commerce, Brian Schatz (D-HI) responded to former NCAA President Mark Emmert’s claim that the NCAA simply wanted to “clarify” that athletes are not employees.

Schatz pushed back at that disingenuous statement, questioned the relevance of the employee issue, and pointed out the profound consequences a no-employee law would have on athletes.

Note that Charlie Baker used the same tactic (“codifying current regulatory guidance into law by granting athletes special status that would affirm that they are not employees”; emphasis added) at the October 17th, 2023, hearing.

To effectuate the NCAA and Power 5’s war on employee status for Power 5 football and men’s/women’s basketball players, several “NIL compensation” bills proposed in Congress beginning in 2020 contain sweeping, absolute prohibitions on athletes being employees.

Bills proposed by Senators Roger Wicker (R-MS) in 2020, Jerry Moran (R-KS) in 2021 and Ted Cruz (R-TX) in 2023 illustrate the anti-employee movement in Congress that has evolved in 2023 into an open war on employee status for Power 5 football and men’s/women’s basketball athletes.

Through their extraordinarily talented lobbyists and public relations spin doctors, the NCAA and Power 5 have obscured their anti-employee campaign by wrapping it in the mythology of the “student-athlete” and making it a civil rights issue for women and HBCUs.