IV. Context for the Timeline

The Timeline tells the story of the Power 5 and NCAA’s quest for unchallengeable authority to regulate college sports without interference from external regulatory threats such as federal courts, federal administrative agencies, Congress, state legislatures, or free markets.

As explained below, these external threats mounted in the 2000s because the Power 5 and NCAA refused to bring their business and regulatory model into the 21st century through voluntary regulation and rule changes.

External regulators were forcing the Power 5 and NCAA to change.

In early 2019, the Power 5 and NCAA began an unprecedented campaign in Congress to eliminate these external threats in one fell swoop. They enlisted the assistance of the most influential lobbying, legal, and public relations experts that athletes’ money can buy.

Much of this campaign has been conducted behind closed doors, outside the scrutiny of most stakeholders.

If the Power 5 and NCAA get what they want from Congress, college athletes will have no legal or regulatory option to assert and protect their rights as Americans.

In a literal way, athletes will become second-class citizens.

This is not a situation where a powerful group of corporate behemoths who manufacture widgets coordinates their efforts to lobby for a tweak to federal law or regulation.

What the Power 5 and NCAA seek from Congress is the wholesale elimination of fundamental American freedoms surgically targeted to an identifiable group of American citizens.

Can the Power 5, the NCAA, and their advocates identify in the post-Civil Rights era another class of American citizens singled out for the elimination of their fundamental rights?

The Timeline covers the period from February 2019 to the present. It chronicles the most audacious regulatory power grab attempt in American sports history.

Congress has held twelve hearings between February 2020 and January 2024—seven in the Senate and four in the House.

While the Power 5’s and NCAA’s values-based justifications for Congressional intervention have changed substantially through the eight hearings, their bottom line has not.

They seek three breathtaking federal protections and immunities in their quest for regulatory supremacy in college sports:

Federal Preemption to Eliminate State Legislatures from the Regulatory Field

The Power 5 and NCAA seek the “preemption” of all state laws that interfere with Power 5/NCAA eligibility rules and amateurism-based compensation limits, including name, image, and likeness and revenue sharing laws.

Preemption is a federal power grounded in Article VI of the United States Constitution, commonly known as the Supremacy Clause. The Supremacy Clause permits the federal government to nullify existing state laws and prohibit states from legislating or regulating in areas that may compromise a vital national interest.

For example, Congress has used preemption to give the federal government exclusive regulatory jurisdiction over nuclear safety, national security, civil rights, the environment, air travel, and drug labeling/advertising.

Preemption is disfavored because it disrupts the carefully calibrated balance of power between states and the federal government.

Using preemption to protect the business interests of private, nonprofit associations like the NCAA and Power 5 conferences would be unprecedented in college sports

Antitrust Immunity to Eliminate Federal Courts from the Regulatory Field

The Power 5 and NCAA also seek from Congress an absolute exemption from our nation’s free competition laws—the Sherman Antitrust Act and the Clayton Act. These federal antitrust laws are designed to protect free markets and prevent unfair market activity.

Agreements among market participants to fix prices or wages violate free competition laws.

The NCAA’s amateurism-based compensation limits are the product of an agreement among member institutions to fix the cost of athlete labor at the value of a full athletics scholarship.

These compensation limits are classic, slam-dunk antitrust violations.

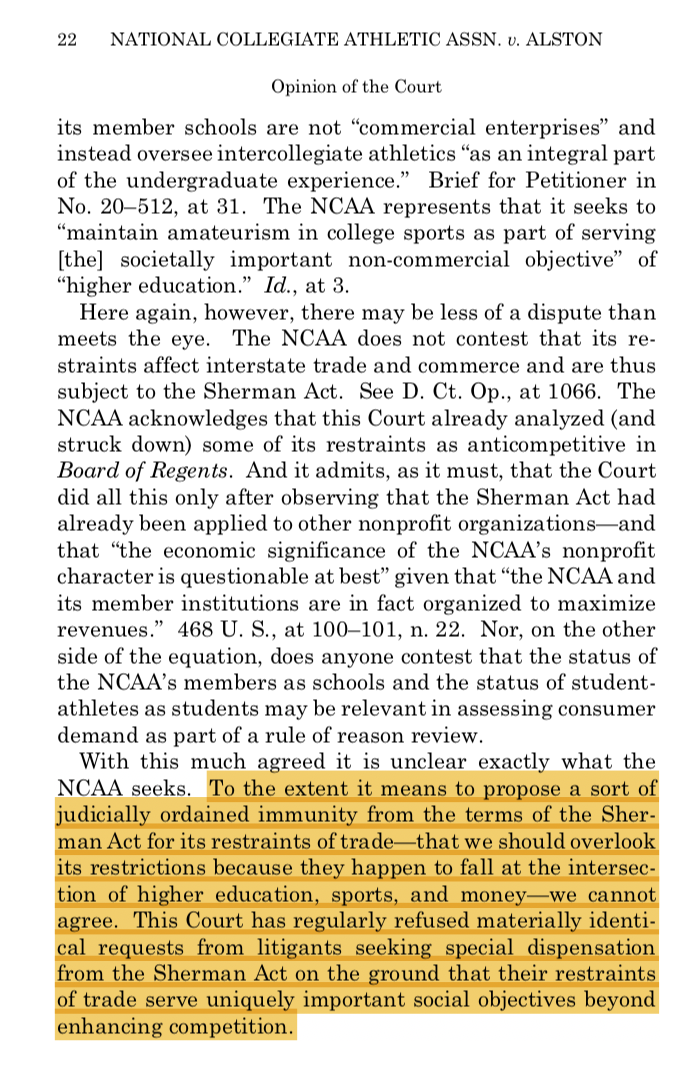

In O’Bannon and Alston, federal courts held that the NCAA’s wage-fixing agreement violated free competition laws in name, image, likeness, and education benefits contexts.

In both cases, the NCAA and Power 5 asked the courts to carve out a sweeping judicially created antitrust exemption that would place the Power 5 and NCAA literally above the law.

A unanimous U.S. Supreme Court rejected that claim in Alston on June 21, 2021.

Rather than comply with federal antitrust/free competition laws, the NCAA and Power 5 seek a bill from Congress that will place them beyond the reach of those laws.

The NCAA and Power 5 want Congress to allow them to impose and enforce amateurism-based compensation limits on college athletes without any legal accountability.

There are four ways the NCAA and Power 5 can attempt to achieve some form of antitrust immunity:

(1) Congressional antitrust immunity, which the NCAA and Power 5 have been sought from Congress since 2019.

(2) Collective bargaining immunity under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), through which the NCAA and Power 5 would receive what’s known as non-statutory collective bargaining antitrust immunity. The NCAA and Power 5 have steadfastly refused to consider this immunity pathway because it would occur in a setting where the NCAA and Power 5 would have to recognize athletes as employees.

(3) Judicially created antitrust immunity through final rulings and binding legal precedent, which the NCAA and Power 5 partially obtained in O’Bannon but failed to fully obtain in Alston.

(4) Settlement-based antitrust immunity through which the NCAA and Power 5 essentially “purchase” immunity by settling class action antitrust cases in whole or part and receiving in return broad releases from past, current, or future liability for the anticompetitive practice at issue.

This Tab focuses primarily on the Congressional pathway to antitrust immunity. However, with the exception of collective bargaining under the NLRA, the NCAA and Power are simultaneously working the avenues identified above.

Note: For a discussion of the judicially created and settlement-based antitrust immunity options, see the Federal Courts Tab in the Explore menu.

Athletes Can’t be Employees of Their Universities

Finally, the Power 5 and NCAA seek from Congress a provision that athletes cannot, as a matter of federal law, be employees of their university.

Such a provision would eliminate any possibility that athletes would benefit from the protections of the National Labor Relations Act, the Fair Labor Standards Act, or any other federal labor law (e.g., EEOC, OSHA, DOL’s Wage and Hour Division) that requires employee status.

In some Power 5/NCAA-friendly proposed legislation, the preemption provisions include “no employee status” language. These provisions may make it impossible for athletes to receive the benefits of state labor laws which also require employee status.

WHO GETS TO DECIDE?

A quote from the magistrate judge overseeing the attorneys’ fees dispute in O’Bannon inspired our use of the Iron Throne/Game of Thrones metaphor illustrated below. In awarding attorneys’ fees to the athletes after six years of brutal litigation, the magistrate judge likened the athletes’ quest for name, image, and likeness rights to the battle for the Iron Throne in :

“[An…apt allusion would have been to George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones, where individuals with seemingly long odds overcome unthinkable challenges but suffer stark losses along the path to victory. In Martin’s world, ‘When you play the game of thrones, you win, or you die. There is no middle ground.’” (emphasis added)

Magistrate Judge Nathanael Cousins (July 13th, 2015])

What is at stake in the future of college sports is as much about who gets to decide as it is about determining the appropriate relationship between athletes and institutions or how much money athletes are paid.

For the NCAA and Power 5, there is no middle ground.

In short, who will sit on the Iron Throne of college sports regulation?

1. The NCAA’s Regulatory Monopoly and Evolving Threats

For nearly seventy years, the NCAA and later the Power 5 have enjoyed a monopoly over college sports regulation. They have occupied the Iron Throne of college sports without any meaningful competition to their regulatory authority and decision-making.

They have held that monopoly for so long they cannot imagine a world in which they must compromise or be told what to do.

However, that began to change in the 21st century as the economic value of big-time football and men’s basketball exploded. The growing tension between the amateur lie and the professional truth became impossible to ignore.

With the NCAA and Power 5 arrogantly indifferent to the hypocrisy in the business model, athletes and their advocates looked to external regulatory pathways to force the Power 5 and NCAA to change. Threats to the NCAA’s regulatory monopoly took several forms, including:

a. Federal class-action lawsuits challenging NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits and regulatory authority:

2006 – White v NCAA (challenging the scholarship limit set below the full cost of attendance)

2009 – O’Bannon v NCAA (challenging the NCAA’s limits on name, image, and likeness compensation)

2014 – Alston v NCAA (initially challenging all amateurism-based limits, then whittled down to education-related benefits)

2019 – Johnson v NCAA (pending; seeking hourly wage benefits under the Fair Labor Standards Act)

2020 – House v NCAA (pending; another name, image, and likeness case)

2023 - Hubbard v NCAA (pending; “back” Alston education benefits)

2023 - Carter v NCAA (pending; all NCAA compensation limits)

2023 - Ohio et al. v NCAA (pending; NCAA one-time transfer rule limitations)

2024 - Tennessee et al. v NCAA (pending; NIL policies and guidance)

b. Federal administrative agency actions

2014 – Northwestern University football team’s attempt to unionize under the National Labor Relations Act (National Labor Relations Board petition; first have to establish employee status)

2022 – NLRB “charge” against USC, Pac-12, and NCAA claiming violation of NLRA

2023 - Dartmouth College men’s basketball teams’ petition with the NLRB to unionize

c. State legislative initiatives

2019 – California NIL Law (Fair Pay to Play Act)

2020 -2021 – multiple state NIL laws

2022 – California revenue sharing bills

2020 – present – laws addressing employee status, most saying athletes cannot be employees

2022 - 2024 - laws challenging NCAA enforcement authority

d. Free markets

With the advent of a NIL market under state laws, executive orders, and the NCAA NIL “Interim Policy” (7/1/2021), free market principles have acted as a potent external regulator of college sports.

Through “natural” market experiments and evidence, the budding NIL marketplace is efficiently proving that athlete compensation will not bring college sports to a fatal collapse.

(For more detailed information about each of these external regulators, see the links from the gateway page to Federal Courts, Administrative Agencies, State Legislatures, and Free Markets.)

2. From “Whac-a-mole” to Trojan Horse: A Comprehensive Strategy

Historically, the Power 5 and NCAA have dealt with such external regulatory threats one at a time—the “whac-a-mole” strategy.

However, as the Timeline portrays, beginning in 2019, the Power 5 and NCAA embarked on a historic and secret campaign to eliminate all external regulatory threats simultaneously.

The name, image, and likeness debate, which heated up in early 2019 with the California Fair Pay to Play Act and the Mark Walker (R-NC) name, image, and likeness bill in the House, offered the Power 5 and NCAA the perfect pretext for engaging Congress to eliminate all external regulatory threats through protective federal legislation.

The Power 5 and NCAA have used NIL “compensation” as a Trojan Horse to engage Congress.

Powerful corporate interests can’t just go to Congress and demand that they be placed above the law. There has to be a compelling justification for Congressional intervention.

Imagine if Walmart, Amazon, or Google went to Congress and asked that (1) states be prohibited from passing legislation that interfered with their business model, (2) they didn’t have to comply with free competition laws, and (3) they didn’t have to treat their labor force as employees.

How would that land with the American public?

Yet that is essentially what the Power 5 and NCAA have done under the guise of “NIL compensation.”

Proof of the Power 5’s and NCAA’s use of NIL as a Trojan Horse is outlined in the NCAA Board of Governors Federal and State Legislation Working Group’s Final Report (Working Group).

The NCAA Board of Governors formed the Working Group on May 14th, 2019 (see Timeline entry for May 14th, 2019) to assess whether the NCAA should maintain its longstanding opposition to NIL compensation or consider changing its NIL rules to make them more permissive.

In the face of mounting criticism of the NCAA’s hostility towards NIL rights, the Working Group led stakeholders and the public to believe the NCAA sincerely desired to change its NIL rules. (see Timeline entries for October 23rd, 2019 and October 29th, 2019).

The Working Group became a primary conduit through which the NCAA sought to use “NIL compensation” as a guise to eliminate external threats to the NCAA’s regulatory authority.

On April 17th, 2019, the Working Group issued its Final Report (see Timeline entry for April 17th, 2019). The Final Report is a thirty-page document written by lawyers for lawyers.

It contains a section on the work of the Presidential Subcommittee on Congressional Action (PSCA). The PCSA was quietly formed at the direction of the Board of Governors Executive Committee on November 16th, 2019.

The Executive Committee tasked the PSCA to explore federal legislation that would protect the status quo business model.

While the NIL debate framed the PSCA’s recommendations on Congressional intervention, the recommendations had little to do with substantive NIL issues.

Pages 26 and 27 of the Final Report (see images below) contextualize the work of the Presidential Subcommittee on Congressional Action (PSCA).

These passages are the “smoking gun” on the NCAA’s true intentions in Congress and using NIL as a Trojan Horse.

The PSCA’s primary goal was to eliminate all external threats to its regulatory authority, not to offer a framework for “NIL compensation.” The PSCA says:

“... the NCAA is the most appropriate and experienced entity to oversee the intercollegiate athletics model given the uniqueness of the collegiate model of athletics, it’s member-driven nature and daily connections to student-athletes, the breadth and scope of its administrative operations, its willingness to respond to the evolving need of student-athletes, and its long track record providing remarkable opportunities for student-athletes to gain access to higher education.’ (emphasis added)

Further, the PSCA says, “[u]nfortunately, the evolving legal landscape surrounding NIL and related issues threatens to undermine the intercollegiate athletics model and significantly limit our ability to meet the needs of student-athletes moving forward. Specific modernization reforms that the working group believes are in the best interests of student-athletes and consistent with the collegiate model might prove infeasible as a practical matter due solely to the legal risk that they might create for the Association.” (emphasis added)

These objectives have nothing directly to do with NIL, except that they are raised in the context of “NIL compensation.”

Only the preemption component is relevant to NIL. The antitrust and “no employee” components have little to do with NIL.

The “no employee” provision is particularly revealing. Employee status is irrelevant to NIL. Every version of NIL legislation or policy explicitly prohibits universities from entering into NIL deals with athletes.

Athletes can only do NIL deals with third parties.

This makes it impossible for athletes to have an employer-employee relationship in the NIL marketplace.

The PSCA’s “no employee” component in federal legislation proves that the NCAA is more concerned with achieving unchallengeable regulatory authority than providing “NIL compensation.”

3. The Power 5’s and NCAA’s Congressional Attack

The Senate’s first “NIL” hearing occurred on February 11th, 2020, over two months before the Working Group released its Final Report in April. The Final Report does not mention the February 11th hearing.

The Power 5 and NCAA built their public relations campaigns on NIL around their desire to “modernize” their rulebook by loosening NIL restrictions.

However, what the Power and NCAA seek from Congress would turn the clock back to the regulatory monopoly they enjoyed throughout the second half of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century.

The “NIL” bills proposed by NCAA/Power 5-friendly legislators would essentially end the athletes’ rights movement and protect the NCAA’s regulatory authority and amateurism-based compensation limits.

Examples include bills proposed by Senators Marco Rubio (R-FL) [see Timeline entry for June 18th, 2020], Roger Wicker (R-MS) [see Timeline entries for December 10th, 2020, and September 14th, 2022], Jerry Moran (R-KS) [see Timeline entry for February 24th, 2021], and Ted Cruz (R-TX) [see Timeline entry for August 2nd, 2023].

These bills share a similar formula:

a. They have an Orwellian title that disguises their true purpose.

b. They hail “NIL compensation” as a good thing for athletes, but only within the framework of amateurism-based “guardrails” that make meaningful NIL compensation almost impossible.

c. Some are “NIL only” to avoid addressing broader athlete well-being issues such as health and safety.

d. They impose draconian credentialing and reporting requirements on athletes, agents, boosters, and NIL companies with penalties for violations.

e. They contain very brief, often cleverly disguised provisions on preemption, antitrust immunity, and no employee status for athletes that would eliminate all legal and regulatory pathways athletes might have to protect their rights.

f. Some bills set up a commission, federal corporation, office of the Federal Trade Commission, or a similar entity to regulate and enforce the bill's requirements. These entities are given substantial law enforcement authority, including subpoena power. Governing board decision-makers on these entities would be drawn disproportionately from NCAA and Power 5 insiders. In essence, these federal regulatory bodies would replicate the NCAA and Power 5 bureaucracies.

g. These bills would make college athletes—particularly profit athletes in Power 5 football and men’s basketball—second-class citizens.

The Moran bill is an illuminating case study. It is approximately 36 pages long with 5,000 words and is titled the “Amateur Athletes Protection and Compensation Act of 2021.” It contains several “shiny objects” beyond NIL “compensation” (e.g., one-time transfer; out-of-pocket health care reimbursement for two years post-eligibility) advertised as meaningful new athlete benefits.

However, when Moran introduced the bill on February 24th, 2021, these “benefits” already existed in the Power 5 through Autonomy legislation (extended medical benefits) or were scheduled to come into existence independently of the bill (one-time transfer).

The NCAA’s and Power 5’s lobbyists have identified the Moran bill as one their clients’ support. The provisions below—preemption, antitrust immunity (“Limitation of Liability”), and no employee status for athletes (“Employment Matters”)—give the NCAA and Power 5 everything they want to rule college sports with a unchallengeable authority.

The Moran bill is frighteningly efficient. It takes down the athletes’ rights movement in 200 words.

This is what the Iron Throne would look like if Congress passes the Moran bill or one like it: