IV. The Legal Firewall the NCAA and Power 5 Have Built Through Federal Litigation

An evaluation of federal litigation against the Power 5 and NCAA raises a question more difficult to answer than one might think:

Who are the “winners” and the “losers” in these cases?

Many believe that federal suits challenging the NCAA’s amateurism-based compensation limits have resulted in substantial progress for athletes.

However, the legal principles from these cases provide significant protections for the NCAA and Power 5.

At least so far, the net effect of federal litigation has been at least as favorable for the NCAA and Power 5 as for athletes.

This Section addresses three categories of post-Board of Regents federal cases: (1) class-action antitrust cases directly challenging NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits, (2) other cases challenging NCAA eligibility rules or employee status that resulted in amateurism-based judicial immunities, and (3) cases in which courts have found the NCAA has no legal duty to athletes.

A. Antitrust Cases Challenging NCAA Amateurism-Based Compensation Limits or Eligibility Rules

America’s free competition laws—the Sherman and Clayton Acts—are designed to protect the integrity and freedom of markets.

Under the Sherman Act, market behaviors such as monopolizing a specific market or agreements among competitors to fix prices or wages are classic antitrust violations.

The Clayton Act emphasizes unfair business practices that could harm consumers, such as illegal mergers and predatory pricing.

Antitrust laws provide civil and criminal penalties to deter anti-competitive behavior. In a civil damages case, an award of damages is automatically tripled.

Since Board of Regents in 1984, antitrust cases in the college sports setting have been analyzed under the “rule of reason” antitrust test, a fact-specific multistep inquiry.

The rule of reason analysis asks several basic questions. First, is there an anticompetitive practice? Second, if so, can the market actor engaging in an anticompetitive practice offer a “procompetitive” justification for the practice? Third, if the market actor offers a plausible procompetitive justification, are there substantially less restrictive means to preserve the justification?

Antitrust law and litigation are complex and often driven by intricate economic and market analyses by experts in the field. It can take years for an antitrust case to reach a final resolution, and the litigation costs are staggering.

Additionally, many antitrust cases are class-action cases, adding another layer to the complexity of the litigation. Defining a class of claimants and then having classes “certified” for eligibility is a painstaking process.

Moreover, thousands of members that may comprise a “class” have only attenuated representation through a minimal number of individuals (sometimes only two or three) who are “representative” of all class members.

Individual class representatives have very little influence on the conduct of the litigation. Class action litigation is a very sophisticated game dominated by lawyers and judges.

Proponents of class action litigation view it as an essential check on abusive corporate practices. Critics argue that the primary winners in class action suits are the lawyers—for both sides. The truth is probably somewhere in the middle.

However, given the importance of class action antitrust litigation in the broader discussion of athletes’ rights, it is fair to ask whether litigation is an effective policymaking and regulatory tool.

Set forth below in chronological order are the key athlete antitrust suits—most class actions—challenging NCAA compensation or eligibility rules.

Three—White, O’Bannon, and Alston—have been litigated to final judgment or settlement (in whole or part).

The remaining antitrust cases—House, Hubbard, Carter, Ohio, et al., and Tennessee, et al.—are pending.

House, Hubbard, and Carter play off the legacy of White, O’Bannon, and Alston.

The Ohio (challenge to NCAA transfer rules) and Tennessee (challenge to NCAA NIL policies that limit third parties’ ability to discuss NIL opportunities with high school and transfer portal prospects) cases focus on Power 5 institutional interests in recruiting.

The NCAA and Power 5 use the threat of these cases to justify their campaigns for antitrust immunity. The NCAA and Power 5 want to operate entirely outside the ordinary operation of our free competition laws.

There are four ways the NCAA and Power 5 can attempt to achieve some form of antitrust immunity:

(1) Congressional antitrust immunity, which the NCAA and Power 5 have sought from Congress since 2019.

(2) Judicially created antitrust immunity through final rulings and binding legal precedent, which the NCAA and Power 5 partially obtained in O’Bannon but failed to fully obtain in Alston.

(3) Settlement-based antitrust immunity through which the NCAA and Power 5 essentially “purchase” immunity by settling class action antitrust cases in whole or part and receiving in return broad releases from past, current, or future liability for the anti-competitive practice at issue.

(4) Collective bargaining immunity under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), through which the NCAA and Power 5 would receive what’s known as non-statutory collective bargaining antitrust immunity. The NCAA and Power 5 have steadfastly refused to consider this immunity pathway because it would occur in a setting where the NCAA and Power 5 would have to recognize athletes as employees.

This Federal Courts Tab addresses only litigation-based immunity issues. However, as discussed below regarding Alston, House, Hubbard, and Carter, it’s important to keep in mind that the NCAA and Power 5 view their litigation and congressional immunity campaigns as interconnected.

White, O’Bannon, and Alston were crucial inflection points in the role of federal courts in college sports because they marked the beginning of class-action antitrust suits directly challenging NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits and posed a new and potent threat to the amateurism-based business model.

Athletes’ rights advocates and some in the media championed each case as “the” case that would bring the NCAA to its knees and its senses.

The “winner” of these cases is in the eye of the beholder, but no case resulted in a fundamental change to the legal relationship between athletes and institutions.

Athletes have no more structural power after White, O’Bannon, and Alston than before.

These cases represent the high-water marks in athletes’ rights litigation thus far.

Class-action antitrust suits pose unique threats to the NCAA and Power 5 and important limitations for athletes.

The cases discussed below involve claims for both damages and injunctive relief.

Damages are designed to compensate victims of anti-competitive market behavior.

Injunctions are designed to regulate (through prohibitions) the behavior of market actors.

Injunctive relief sometimes includes potential “compensation,” as was the case in O’Bannon (permissive full cost of attendance scholarships through an injunction that prohibited a scholarship limit set below the full cost of attendance) and Alston (permissive education benefits that prohibited a cap on education benefits set below what athletes could receive for athletic performance awards).

Because an award of compensatory damages is automatically tripled (“treble” damages) under federal antitrust laws, the NCAA and Power 5 have enormous incentives to settle the damages component of class action antitrust suits.

Indeed, a pattern has developed so far in athlete-initiated antitrust litigation where the NCAA and Power 5 settle damage claims and litigate injunctive relief claims.

They settled damage claims in O’Bannon ($40 million) and Alston ($208 million) and may try to settle House (NIL-related), Hubbard (“back” Alston education benefits), and Carter (challenge to all compensation limits).

Litigants can also settle injunctive relief claims, essentially negotiating a new regulatory landscape.

Jeffrey Kessler, who represented athletes in Alston and now represents athletes in House, Hubbard, and Carter, has advocated for the NCAA to settle all three cases.

Mr. Kessler suggests that such a settlement (presumably including injunction terms) could resolve most athlete compensation and perhaps some regulatory issues.

In any global settlement, the NCAA and Power 5 would receive sweeping releases from past, current, and future liability for their anti-competitive behaviors.

In essence, the NCAA and Power 5 would purchase comprehensive antitrust immunity without having to acknowledge athletes as employees.

Suppose such a settlement occurs, and there is a perception that athlete compensation issues have been adequately addressed.

In that case, the NCAA will likely have renewed momentum to go to Congress and obtain federal legislation that prohibits athletes from being employees and also preempts state laws that address compensation issues (NIL, revenue sharing).

Mr. Kessler has also suggested that class-action antitrust litigation is more effective as an agent of change for athletes than negotiated collective bargaining through the NLRA.

Mr. Kessler rightly points out that any possibility of meaningful collective bargaining is uncertain and will not occur in the next several years.

However, a global settlement strategy combined with a federal bill prohibiting employee status would make it impossible for athletes to force the NCAA and Power 5 to address noneconomic issues such as health and safety standards, work conditions, and athlete representation in the future.

These are critical issues in the broader athletes’ rights movement.

Federal class-action antitrust litigation has undoubtedly been the most effective weapon in the athletes’ arsenal thus far.

However, it has proven necessary primarily because of the profound dysfunctions in the college sports regulatory environment, the NCAA and Power 5’s manipulation of the political process, and their historic refusal to change on their own.

Antitrust litigation has forced the NCAA and Power 5 to change, and they don’t like it.

Mr. Kessler is a preeminent antitrust and sports law attorney. He has extensive experience in professional sports litigation and is now poised to have a dominant voice in shaping the future of college sports. His opinion matters.

But from a policy and practical standpoint, should antitrust litigation be viewed as a complement to future collective bargaining or a permanent substitute?

In asking these questions, we do not mean to minimize the economic benefits athletes have received as a direct result of litigation. For many athletes—particularly athletes from modest financial circumstances—the full cost of attendance scholarship (approximately $2,000 - $5,000 per year) and the Alston education benefit ($5,980 per year) are critical to their well-being.

However, the benchmark for measuring these permissive benefits is what the athletes didn’t have before rather than their actual market value to the college sports commercial enterprise.

Note: In our Deep Dive materials, we will analyze the benefits and limitations of class-action antitrust litigation, including the aggregate effect of injunctions and settlements so far and what a global settlement scenario may look like for athletes.

As we tour the catalog of antitrust suits below, resolved and pending, it may be helpful to keep in mind several questions: (1) What was/is the goal of the suit? (2) Did the suit attain its original goals? (3) Has the litigation altered the legal relationship between athlete-laborers and institutional beneficiaries? (4) do athletes have more structural power as a result of these suits? (5) Is class-action antitrust litigation an adequate substitute for direct athlete representation through collective bargaining on issues beyond compensation?

1. White v NCAA (2006 - 2008)

In White v NCAA, athletes sued under class-action and antitrust laws to force the NCAA to offer the full cost of attendance scholarship (FCOA). The FCOA is essentially a living expenses stipend (from $2,000 - $5,000 per year) to cover the sundry costs of college life.

From 1956 - 1975, the full athletic scholarship included a similar (monthly) stipend known as “laundry money.” The FCOA served essentially the same purpose.

In 1975, the NCAA eliminated laundry money from the athletic scholarship, ostensibly as a cost-cutting measure.

After 1975, the NCAA opposed the FCOA scholarship not because it was too expensive but because it violated NCAA amateurism rules. The NCAA aggressively defended the White suit.

Former NCAA President Myles Brand said in an October 2006 speech to the National Press Club that the FCOA “stipend” would transform college athletes from amateurs into professionals.

The media portrayed White as a potential blockbuster suit that would advance athletes’ rights.

However, in 2008, White settled with a whimper. The athletes got very little, the NCAA retained its scholarship below the full cost of attending college, and a handful of lawyers made good money.

2. O’Bannon v NCAA (2009 – 2016)

O’Bannon, like White, was initially portrayed as a potentially fatal blow to amateurism.

O’Bannon was a class-action federal antitrust suit challenging the NCAA’s amateurism-based compensation limits on name, image, and likeness (NIL).

The athletes sued the NCAA and Power 5, seeking damages and injunctive relief. Importantly, O’Bannon challenged only NIL limits. The athletes did not ask for broader relief.

O’Bannon brought celebrity power to the fight. Former UCLA basketball star Ed O’Bannon was the face of the case, and basketball legends Oscar Robertson and Bill Russell were class representatives.

The NCAA and Power 5 openly and aggressively sought judicially created antitrust immunity in O’Bannon. They presented that argument as a threshold defense.

The essence of their immunity claim was that as private education nonprofits, they do not engage in commercial activity and are, therefore, outside the scope of the Sherman Antitrust Act.

The NCAA bolstered its immunity claim with the magic dicta from the Board of Regents case in 1984 that mused the virtues of amateurism.

Alternatively, the NCAA and Power 5 argued that amateurism-based compensation limits were “procompetitive” and necessary for the product to exist from a consumer welfare standpoint.

Essentially, the NCAA and Power 5 argued that if athletes were paid for NIL or anything else, consumers would flee because they prefer to watch college athletes who were paid nothing, and the college sports market would collapse.

After five years of contentious litigation and a full bench trial, District Court Judge Claudia Wilken issued an opinion that fell far short of taking down amateurism.

Judge Wilken found that the NCAA and Power 5 were subject to antitrust scrutiny and that NCAA NIL compensation limits violated antitrust laws. However, her legal analysis and the remedies she issued were in many ways deferential to the NCAA’s conceptualization of amateurism.

She crafted two remedies as NIL compensation: (1) the NCAA could not set a scholarship limit below the FCOA, and institutions were permitted but not required to offer the FCOA, and (2) schools were permitted but not required to establish NIL trust funds of up to $5,000 per athlete per year available upon graduation.

Both parties appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

In 2015, in a 2-1 opinion, the Ninth Circuit upheld the permissive FCOA scholarship but struck down the trust fund remedy.

The NCAA renewed its amateurism-based request for absolute antitrust immunity, arguing that the Sherman Act did not apply at all to the NCAA because the NCAA was not engaged in commercial activity.

The majority agreed with the District Court that the NCAA and Power 5 were indeed subject to the full application of antitrust laws.

However, at the same time, the majority’s rejection of the trust fund remedy was based on blind deference to amateurism.

The majority distinguished athlete benefits that were connected to education and those that were not. Education-related benefits may be permissible, but non-education-related benefits would imperil amateurism and may lead to an open and free market for the value of athletes’ services.

Because the FCOA remedy was tied to the athletic “grant-in-aid,” it was deemed education-related. The trust fund remedy, in contrast, was considered unrelated to education and, therefore, a potential threat to amateurism.

The dissenting judge—Sidney Smith—took issue with the majority’s use of amateurism. He argued that amateurism was relevant only in the context of consumer welfare and choice, but the majority used amateurism as a free-standing value that operated independently of antitrust law.

In essence, the majority opinion created a partial amateurism-based antitrust immunity for the NCAA and Power 5 for any payments unrelated to education.

The Ninth Circuit’s ruling protected the NCAA and Power 5 from what they perceived as the greatest threat to their business model and revenue streams: an open and free market for the full value of athletes’ NIL and, perhaps in the future, an open market for the full value of athletes’ services.

Both parties appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to hear the case.

What is the net result of O’Bannon?

First, athletes have the possibility of an FCOA scholarship and a symbolic ruling that the NCAA and Power 5 are subject to antitrust scrutiny.

Second, the NCAA and Power 5 received a de facto antitrust immunity from the greatest threat to their interests—a full and free market for the value of athletes’ services.

O’Bannon’s failure to deliver meaningful change on NIL compensation was a substantial motivating factor in the California legislature’s passage of its 2019 NIL law, SB 206, or the “Fair Pay to Play Act.”

Note: For a detailed discussion of SB 206, see the State Legislatures and Congress Tabs in the Explore menu.

While the NCAA and Power 5 still use the threat of suits like O’Bannon as looming, pervasive, existential threats to college sports, they are privately thrilled with the outcome in O’Bannon.

The benefit of O’Bannon to the NCAA and Power 5 as an amateurism-based immunity shield is certainly not lost on NCAA advocates in Congress or NCAA lawyers.

On February 11th, 2020, the Senate Commerce Subcommittee on Manufacturing, Trade, and Consumer Protection held the first hearing ostensibly on name, image, and likeness “compensation” (“Name, Image, and Likeness: The State of Intercollegiate Athlete Compensation”).

Senator John Thune (R-SD), a reliable NCAA/Power 5 ally, went off-script and acknowledged that the NCAA/Power 5 essentially had immunity from claims seeking benefits/compensation beyond the nominal, permissive FCOA:

Thune: Dr. Emmert, as I understand the NCAA ban on athletes profiting from the use of their names, images, and likenesses violates federal antitrust law, but the federal appellate court in the Ninth Circuit [in O’Bannon] has ruled that the NCAA essentially holds an antitrust exemption so long as it allows its member schools the chance to offer college athletes the full cost of attendance.

How would the name, image, and likeness rules that you're considering likely impact the NCAA’s antitrust exemption? (emphasis added)

While Thune’s characterization of O’Bannon’s impact was perhaps oversimplistic, he captured the essence of the immunity issue.

Yes, the NCAA’s compensation limits on NIL violate antitrust laws, but the NCAA “essentially holds an antitrust exemption” for its amateurism-based compensation limits outside the nominal, permissive FCOA.

True to form, Emmert skirted the question and avoided acknowledging the NCAA’s antitrust immunity from O’Bannon. The O’Bannon immunity was an inconvenient subject in Congress because the NCAA and Power 5 wanted decision-makers to believe the NCAA had no antitrust protection and was always one lawsuit away from extinction.

Emmert’s rambling response to Thune:

Part of the conversation that's going on right now, Senator, and again thank you for that equally important question. Part of the discussions that are going on right now is to try and address precisely the question you're asking.

The Association schools are deeply committed to maintaining the college model and making sure that we can adhere to the values that are consistent with the legal precedents that exist and how college sports has gone on for a great deal of time. So, threading the needle is trying to determine how can we expand opportunities because there is a general agreement that providing greater opportunity for students around their name, image, and likeness is a very good thing.

But doing that in a way that doesn't immediately provoke antitrust litigation around the actions of the Association. How can we make sure that we can do good without immediately being back in court is one of the greatest problems that we have right now.

During oral argument in the Ninth Circuit in Alston on March 9th, 2020, NCAA attorney Seth Waxman built his opening statement around O’Bannon’s deference to the NCAA’s conceptualization of amateurism.

Waxman did not couch O’Bannon’s benefit in terms of an explicit antitrust immunity, but he makes clear that O’Bannon was a victory for the NCAA:

“Amateurism as reflected in the NCAA's rules and recognized in O’Bannon, prohibits athletic-related compensation beyond covering legitimate expenses or modestly recognizing achievement. Yet the district court's injunction would permit colleges, sponsors, and boosters to recruit athletes with promises of internships that pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash [and] new cars to get to class. Colleges can promise to pay thousands of dollars in cash each year that any student-athlete remains academically eligible to play and can also promise other lavish benefits…so long as they are somehow nominally related to education.

O’Bannon should have barred this suit from the outset.” (emphasis added)

It’s revealing to look at the NCAA’s portrayal of the Alston education injunction with the benefit of hindsight. In March 2019, the NCAA predicted hundred-thousand-dollar internships, luxury automobiles, and other “lavish” benefits.

Nothing on the NCAA’s parade of horribles list has come true.

There has not been an education benefits arms race, and less than half of FBS schools offer Alston benefits. Of those that do, many offer less than the maximum ($5.980), and the eligibility criteria vary from school to school.

3. In re Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Litigation (“Alston”) (2014 – 2021)

During the O’Bannon litigation—five months before Judge Wilken issued her final opinion—two other groups of athletes sued the NCAA and Power 5 under federal antitrust laws.

On March 5, 2014, Power 5 football and men’s/women’s basketball athletes filed a class-action suit in the Northern District of California—Alston v NCAA—alleging that the NCAA’s scholarship limit set below the full cost of attending college violated federal antitrust laws.

Alston was similar in theory to the White suit eight years earlier and sought damages and injunctive relief against the NCAA and Power 5. Alston was assigned to Judge Wilken.

Just twelve days later, on March 17, another group of athletes filed a federal antitrust suit in New Jersey—Jenkins v NCAA—challenging all NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits.

Jenkins sought to deliver a knockout punch to amateurism itself. It aimed to open to the free markets the full value of athletes’ services and do for athletes what Board of Regents did for big-time football.

Jenkins did not seek class damages. it sought damages only for the named plaintiffs. Jenkins’ primary goal was an injunction (on behalf of a class) prohibiting the NCAA and Power 5 from enforcing any compensation limits.

Soon after Jenkins was filed, the athletes in Alston asked the United States Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation (USJCMDL) to transfer Jenkins to Judge Wilken in the Northern District of California and consolidate it with Alston.

The USJCMDL coordinates and consolidates similar federal cases nationwide to achieve (in theory) judicial economies.

The Jenkins athletes opposed the transfer and wanted Jenkins to remain in New Jersey. The NCAA (and conference defendants) likewise objected to transfer and wanted the cases litigated in federal court in Indianapolis, the NCAA’s “home court.”

On June 13, 2014, the USJCMDL—noting the common questions of law and fact between the two cases—issued an order to join Jenkins with Alston in California. The USJCMDL renamed the consolidated cases “In Re: National Collegiate Athletic Association Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litigation.”

The consolidated cases came became known in the public arena as “Alston.”

Note: For convenience, we use the name “Alston.”

The USCJMDL’s transfer of Jenkins to California and Judge Wilken had several important consequences belied by what seemed to be a ministerial procedural maneuver to promote judicial efficiency.

First, the consolidation brought together a dream team of antitrust lawyers.

Jeffrey Kessler (Winston and Strawn law firm) represented the athletes in Jenkins. Kessler built his reputation representing professional athletes. He is considered among the best sports law attorneys in the country. Kessler’s foray into college sports litigation was perceived by many as a game-changer for athletes.

Steve Berman (Hagens Berman law firm) represented the initial Alston class. Berman has an eye-popping resume in class-action antitrust litigation, and his practice is not limited to sports issues. In 1998, acting as a special assistant attorney general for thirteen states in cases against the tobacco industry, Berman secured a $206 billion settlement—the largest in history.

In what initially appeared to be a forced partnership, Berman and Kessler have become solid and formidable teammates. They have joined forces in House, Hubbard, and Carter (discussed below), all currently pending in the Northern District of California before Judge Wilken.

Second, the USJCMLD’s consolidation of Jenkins and Alston substantially reduced the likelihood that a federal circuit outside the Ninth Circuit would be able to analyze and rule on athlete-initiated antitrust cases challenging NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits.

For example, suppose athletes in Hubbard or Carter sued in another federal circuit. In that case, the USJCMDL could send those cases to the Northern District of California.

While consolidation may promote judicial economy, it also curtails the development of the law in athletes’ rights cases by reducing (or eliminating) the possibility that a court in another federal circuit would evaluate athlete cases differently than the California courts.

The NCAA and some in the college sports commentariat have criticized Judge Wilken as biased against the NCAA and the athletes’ attorneys as opportunistic for filing suits in the Northern District of California.

These criticisms are misplaced.

As a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court noted in Alston, Judge Wilken faithfully and fairly applied long-standing principles of antitrust law in crafting her final order and injunction.

Moreover, as noted above, the athletes’ attorneys could likely have wound up in the Northern District of California if they filed in another circuit.

Additionally, the Carter case has been assigned to Northern District Chief Judge Richard Seeborg, not Judge Wilken.

a. The Alston District Court Decision and the Impact of the Ninth Circuit’s O’Bannon Ruling

Alston was filed in March 2014 before Judge Wilken’s final opinion in O’Bannon (August 2014) and before the Ninth Circuit issued its opinion in O’Bannon (May 2015).

Thus, the Ninth Circuit’s amateurism-based prohibition on payments unrelated to education became binding law on the Alston litigants early in the litigation and substantially influenced the athletes’ central claims designed to dismantle all NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits.

O’Bannon’s partial antitrust immunity (for payments unrelated to education) posed a formidable barrier to the athletes.

As the Alston litigation unfolded in the district court, Judge Wilken conformed the Alston claims to the O’Bannon education-non-education framework.

As a result, Alston was essentially whittled down to whether NCAA amateurism-based limitations on education benefits violated antitrust laws.

This framing of the case was a victory for the NCAA and Power 5.

On March 8th, 2019, after a full bench trial, Judge Wilken issued a modest injunction. She held that the NCAA’s education limits violated antitrust laws and provided a limited set of permissive education-related benefits as a remedy. The way the injunction was structured, these benefits maxed out at $5,980.

Judge Wilken essentially “benched” the NCAA and put the conferences in charge to determine whether the education benefits would be paid. The conferences could provide some, all, or none of the benefits so long as they did not engage in anticompetitive cooperation.

As illustrated in the Timeline in the Congress Tab of the Explore menu, the Alston litigation unfolded coincidentally along the same timeframe as the NIL debate in Congress and in California with the introduction of SB 206.

Mark Walker (R-NC) introduced the first federal bill on NIL in March 2019, and California enacted the Fair Pay to Play Act in September 2019.

The NCAA’s and Power 5’s litigation and congressional strategies became intimately interwoven from 2019 – 2021.

Both forums provided a chance for antitrust immunity, and the NCAA/Power 5 managed these forums simultaneously, playing one off against the other from a timing standpoint.

Timeline entries in the “Congress” tab from May 2020 – to June 24, 2021, highlight the NCAA’s and Power 5’s clock management in both forums.

b. The Alston Ninth Circuit Decision

After the district court’s ruling, the NCAA and Power 5 appealed to the Ninth Circuit. Relying on O’Bannon, they argued that Judge Wilken’s injunction exceeded O’Bannon’s limitations because schools could use “education benefits” to justify hundred-thousand-dollar “internships” and pricey cars.

The athletes cross-appealed to keep alive for Ninth Circuit review their claim that all NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits violate antitrust laws.

As in the district court, the NCAA and Power 5 argued that the injunction opened the door to outright pay-for-play.

In fact, the injunction order had minimal potential financial impact on universities and was not an existential threat to amateurism—and the NCAA/Power 5 knew it.

The NCAA’s opposition to the injunction order was grossly out of proportion to the risk it posed, which is also ironic since the NCAA and Power 5 conferences operate as education nonprofits.

So why did the NCAA and Power 5 appeal Alston to the Supreme Court?

Because they sought absolute judicially created antitrust immunity from all compensation limits, not just those pertaining to NIL compensation or education benefits.

However, unlike O’Bannon, where the NCAA’s claim for antitrust immunity was a primary threshold defense, the NCAA and Power 5 disguised their immunity argument in Alston.

The NCAA relegated the immunity issues in Alston to a single, short footnote in the NCAA’s and Power 5’s joint opening brief in the Ninth Circuit:

“In O’Bannon, this Court disagreed with the NCAA that its amateurism rules are valid as a matter of law under Board of Regents [cite omitted]. Defendants [NCAA/Power 5] preserve this argument for further review.” (Defendant’s Joint Opening Brief, pg. 25, note 2)

Why did the NCAA and Power 5 bury their intentions on antitrust immunity in a cryptic, thirty-word footnote?

Because they were simultaneously managing two potential bites at the antitrust immunity apple in two different forums—Alston and Congress.

The footnote technically preserved for review (by the Supreme Court) the Power 5’s and NCAA’s claim for judicially created antitrust immunity without drawing attention to it.

Power 5 and NCAA lawyers didn’t want the judges in Alston to focus on their evolving congressional campaign for antitrust immunity.

At the same time, the Power 5 and NCAA did not acknowledge in Congress their quest for judicially created antitrust immunity in Alston.

On May 18th, 2020, the Ninth Circuit issued its opinion upholding Judge Wilken’s injunction order in all respects. The Court also rejected the athletes' claim for a broader attack on all NCAA’s amateurism-based limits because O’Bannon prohibited pay-for-play payments.

Judge Milan Smith issued a concurring opinion that would have implications in House (and potentially Hubbard and Carter).

Judge Smith observed that the Court had no choice but to analyze the case within the framework of O’Bannon because it was a binding precedent. Smith believed that O’Bannon’s practical antitrust immunity for payments unrelated to education was inconsistent with antitrust law.

Smith explained that “[a]lthough the district court correctly applied our precedents, the result of this analysis seems to erode the very protections a Sherman Act plaintiff has the right to enforce. Here, Student-Athletes are quite clearly deprived of the fair value of their services.” (emphasis added)

Smith also believed the O’Bannon court improperly defined the relevant market in assessing the NCAA’s amateurism-based justifications for its NIL compensation limits.

Rather than defining the market as a labor market between athletes and schools, O’Bannon used a consumer market where the interests of consumers were the primary concern.

This “cross-market” analysis elevates the interests of consumers who weren’t participants in the labor market over the interests of athletes. Smith argued that a consumer-facing market analysis denied athletes the basic protections of antitrust law.

Smith said: “we leave Student-Athletes with little recourse under antitrust laws. Student-Athletes are thus denied the freedom to compete and, in turn, ‘of compensation they would receive in the absence of the restraints.’”

Soon after the favorable Ninth Circuit opinion in Alston, the Power 5 and NCAA ramped up their campaign in Congress.

On May 23rd, 2020, just five after the Ninth Circuit’s decision, the Power 5 conference commissioners sent a joint letter to both chambers of Congress asking for preemption, antitrust immunity, and a provision that athletes cannot be employees of their institution.

They pleaded that “time is of the essence.”

During this crucial time in 2020, Power 5 and NCAA lawyers and lobbyists employed a sophisticated clock and forum management strategy in federal court via Alston and in Congress.

c. The NCAA/Power 5 Appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court

As the Congressional campaign intensified, the NCAA and Power 5 delayed the deadline to file an appeal with the US Supreme Court through procedural machinations.

They hoped to get antitrust immunity from Congress, potentially eliminating the need to appeal Alston to the U.S. Supreme Court for a shot at judicially created immunity.

The NCAA sought extensions of time in the Ninth Circuit to consider an appeal to the full Ninth Circuit (an “en banc” appeal where all judges hear the case, not just the three-judge panel).

The NCAA/Power 5 decided against the en banc appeal and instead filed a motion to “stay” or stop the Alston injunction from going into effect pending a potential appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Ninth Circuit and the Supreme Court denied the Power 5/NCAA requests for a stay.

The NCAA and Power 5 then sought and obtained an extension of time from the Supreme Court to file an appeal.

Finally, on October 15th, 2020, after four hearings in a friendly Republican Senate failed to yield meaningful progress in Congress, the NCAA and Power 5 filed their appeal request in the US Supreme Court.

It’s crucial to understand that the NCAA and Power 5 appealed to the Ninth Circuit and the Supreme Court, not the athletes.

The NCAA and Power 5 used the appeals process as a first-strike weapon in their quest for absolute antitrust immunity.

U.S. Supreme Court appeals are discretionary and rarely granted. The initial briefing in the appeal focuses on whether the Court should accept the case for review.

After the briefing is completed on that threshold question, the Justices “conference” and decide whether to accept the case and evaluate it on its merits. Four Justices must say yes.

On December 16th, 2020, the Court announced it had granted the NCAA’s appeal.

The parties then submitted another round of briefs on why they should prevail.

An important consequence of the Supreme Court briefing was a critical strategy call by the athletes and their attorneys.

The athletes chose not to file a cross-appeal—as they did in the Ninth Circuit—to keep alive the original purpose of their lawsuit: a frontal attack on all NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits.

Instead, the athletes sought only the affirmance of Judge Wilken’s injunction permitting modest education-related benefits.

This meant that the Supreme Court appeal did not address one of the most important questions in college sports history—the legitimacy of amateurism itself.

Instead, the case, as framed by the athletes, operated within the partial antitrust immunity granted to the NCAA in O’Bannon. That immunity was carried into Alston as binding precedent.

Only the Supreme Court had the authority to alter or overrule O’Bannon.

At oral argument in the Supreme Court on March 31st, 2021, Justice Sonia Sotomayor erased any doubt about the scope of the athletes’ claims on appeal in this exchange with Jefferey Kessler:

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Counsel, you declined to cross-petition the judgment below, correct?

MR. KESSLER: Yes.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: So, for purposes of this Court's review, you are not asking for any broader relief than that already provided by the district court, correct?

MR. KESSLER: That is correct, Your Honor.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: You're not asking us to address the issues that Justice Alito or others, including Justice Kavanaugh, have raised on whether or not there should be any limits, educational or noneducational? You're happy with the injunction you got?

MR. KESSLER: We are not asking for broader relief than affirming the rulings below.

This may have been the most consequential exchange in the oral argument.

Later, in an exchange with Justice Brett Kavanaugh, Kessler elaborated on his clients’ decision to seek only an affirmance of the injunction:

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: -- sorry to interrupt, but your position, I think, in the district court was that all the compensation limits are contrary to the rule of reason, correct?

MR. KESSLER: Yes, and I lost that, as a matter of fact. And they've now won on that issue twice, as a matter of fact, under the rule of reason. And facts would probably have to change further for a different result to happen. If there are new material facts in the future, then we know under antitrust law, the rule of reason could come out differently at a future date. But I have no reason to think that I can win today on facts that I just lost on yesterday.

This framing of the case gave the NCAA and Power 5 essentially a “free shot” at absolute judicially created antitrust immunity.

At worst, the NCAA and Power 5—if they failed to obtain antitrust immunity—would have had to deal with a modest injunction permitting but not requiring a limited set of education benefits that posed virtually no financial risk to the business model or status quo.

On June 21st, 2021, the Supreme Court issued its unanimous opinion in Alston. The court rejected the NCAA’s and Power 5’s quest for judicial antitrust immunity and upheld the limited injunction permitting certain education benefits.

Importantly, the Court also gave the Board of Regents amateurism dicta a final burial.

The Court made clear that its ruling merely affirmed the injunction order and did not address the ultimate issue of whether all amateurism rules violated antitrust laws.

Just as the NCAA and Power 5 had a free shot at judicially created antitrust immunity, the Supreme Court had a free shot to send a message to the NCAA without ruling on the legitimacy of amateurism itself.

However, in his concurring opinion, Justice Kavanaugh questioned the validity of the NCAA’s remaining amateurism-based rules, suggesting they may be vulnerable.

While Kavanaugh’s titillating concurrence dominated the media’s portrayal of Alston, no other Justice signed onto it.

It is impossible to know whether five justices would have struck down all amateurism-based compensation limits if the issue had been preserved on appeal and presented to the court.

It is likewise impossible to predict whether the Supreme Court will be inclined to hear another college sports/athletes’ rights case in the near future.

d. Alston’s Impact

The ultimate impact of Alston is not clear.

Athletes’ rights advocates and the public view Alston as a transformative milestone. While the decision's unanimity was powerful, it is mostly symbolic because it operated within O’Bannon’s substantial limitations.

As noted above, there has not been an education benefits “arms race” as the NCAA and Power 5 predicted.

As with O’Bannon, the NCAA uses Alston for different strategic purposes, depending on the audience and the needs of the moment.

In Congress and for public relations purposes, the NCAA and Power 5 argue that Alston prevents them from enforcing their own rules due to fear of additional antitrust lawsuits. This interpretation reinforces the perception that the NCAA is in a regulatory crisis over which it has no control and also supports its claims for antitrust immunity from Congress.

However, in litigation, the NCAA and Power 5 characterize Alston as a win. For example, in Johnson v NCAA, currently pending in the Third Circuit (discussed in more detail below), the NCAA and the SEC (through a friend of the court brief) argued that Alston actually endorsed NCAA amateurism-based limits for compensation unrelated to education.

The NCAA’s portrayal of Alston in the Johnson case seems to be rooted in a misguided theory of affirmation by negative implication.

In fact, the Supreme Court was not called upon to decide, nor did it decide, that the NCAA’s no pay-for-play limits are presumptively legitimate under antitrust laws.

But the NCAA’s interpretation of Alston in Johnson case begs a critical question: if Alston affirmatively endorsed the NCAA’s no pay-for-play rules, why has the NCAA refused to enforce those rules in a NIL marketplace they have characterized as chaos and outright pay-for-play?

As always, the NCAA and Power 5 want to have it both ways. To federal courts, they pitch Alston as a major victory; to Congress and the public, they pitch Alston as an existential threat to college sports and a justification for regulatory paralysis.

Perhaps the most important question post-Alston is whether federal judges will continue to blindly defer to amateurism-based principles.

In Johnson, the sole question presented to the Third Circuit is whether athletes, as a matter of law, can be employees under the FLSA.

At oral argument on February 15th, 2023, the Third Circuit panel appeared hostile to the NCAA’s amateurism-based arguments.

If the Third Circuit allows the case to go forward, will that be evidence the federal judiciary is willing to abandon its historical fealty to amateurism?

4. House v NCAA (June 15 2020; pending)

On June 15th, 2020, just weeks after the Ninth Circuit issued its opinion in Alston, another group of athletes filed a class-action antitrust suit—House v NCAA—in the Northern District of California assigned to Judge Wilken.

Athletes in House seeks damages for name, image, and likeness (NIL) compensation the athletes claim would have been paid to them “but for” the NCAA’s NIL compensation prohibitions. They also seek injunctive relief.

The NCAA and all Power 5 conferences are defendants in the suit.

Steve Berman, who represented athletes in O’Bannon and Alston, represents the athletes in House and was the sole attorney of record when the case was filed.

House added two new and significant elements to the class action antitrust cases.

First, the athletes defined the relevant market as a labor-facing market rather than a consumer-facing market. This approach aligned with Ninth Circuit Judge Milan Smith’s concerns in Alston that the consumer “cross-market” analysis undermined athletes’ rights under antitrust laws.

Second, the athletes emphasized a claim for NIL payments from broadcast media deals (“BNIL”), which is essentially group licensing.

House is a significant threat to the NCAA because of the potential damages, particularly for BNIL. Damage estimates across the various damages subclasses exceed $1.5 billion. If the athletes receive an award of damages at trial, it is automatically tripled under federal antitrust laws.

The case has progressed through several important class action litigation milestones—denial of the NCAA’s motion to dismiss, a consolidated amended complaint post-NCAA Interim NIL Policy, the certification of the damages class, and the Ninth Circuit’s denial of the NCAA’s request to reverse the order granting certification of the damages class—and now sits at a crucial juncture for the NCAA in terms of litigation and settlement strategy.

a. NCAA Motion to Dismiss

On September 11, 2020, the NCAA and Power 5 filed a motion to dismiss the entire lawsuit.

The NCAA/P5 argued that the athletes’ claims in House were identical to those in O’Bannon and could not be relitigated under principles of precedent.

They also argued that athletes could not assert claims for BNIL because athletes have no legally protectable publicity rights in broadcasts of football or men’s basketball games.

On June 24, 2021, just three days after the U.S. Supreme Court’s 9-0 ruling in Alston, Judge Wilken issued an order denying the NCAA’s motion to dismiss.

Judge Wilken held that the athletes’ claims were sufficiently different from the O’Bannon claims factually to allow the case to go forward.

Additionally, and importantly, she also relied heavily on the fact that the athletes were pursuing an entirely different legal theory by framing the relevant market as a labor market rather than a consumer market. Judge Wilken quoted liberally from Judge Smith’s concurring opinion in Alston.

The new labor-facing market analysis may allow the athletes in House to operate outside the limitations of the Ninth Circuit’s O’Bannon decision.

However, it’s important to note that in analyzing a motion to dismiss, the court is not making a final decision on the issues raised. It simply says the complaint plausibly alleges a cause of action, and the case can go forward.

b. The July 26, 2021, Consolidated Amended Complaint

The athletes’ amended complaint is significant for three reasons.

First, it was filed after the NCAA adopted the Interim NIL Policy on July 1, 2021, which suspended enforcement of certain NIL-related restrictions for athletes in states not governed by a state NIL law or executive order.

The Interim Policy retained prohibitions on school payments (”pay-for-play) or payments as recruiting inducements.

The Interim Policy is effective until (1) the NCAA changes its rules on NIL or (2) the NCAA obtains protective federal legislation on NIL.

Thus, after July 1, 2021, the NIL market was no longer hypothetical, and some free market principles were allowed to operate in athletes’ favor.

This eliminated the NCAA’s claims that any NIL damages were speculative. It also permits athletes to generate real-world evidence of their NIL market value, at least with respect to third-party NIL payments.

Second, the amended complaint leaned more into the labor-facing market definition than the original complaint.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, Jeff Kessler joined Berman as co-counsel, bringing the two together again in a suit against the NCAA and Power 5.

c. Orders Granting Certification of the Injunctive Relief and Damages Classes

Injunctive Relief Class

On September 22, 2023, the court granted the athletes’ motion for certification of the injunctive relief class. The NCAA and Power 5 did not oppose the motion.

The athletes seek an injunction prohibiting the NCAA and Power 5 from (1) enforcing the challenged NCAA NIL restrictions and (2) declaring the challenged rules/policies void.

The injunctive relief class was defined as “All college athletes who compete on, competed on, or will compete on a Division I athletic team at any time between June 15, 2020, and the date of judgment in this matter.”

The certification of the injunctive relief class was expected and did not expose the NCAA and Power 5 to meaningful financial risk.

Damages Classes

On November 3, 2023, Judge Wilken granted the athletes’ motion to certify the damages class.

The class certification ruling on damages in an antitrust case is a “make-or-break” milestone in the litigation. A grant of class certification for damages places enormous pressure on defendants to settle, and a denial of certification on damages may end the suit.

The athletes asked the court to certify three proposed damages classes:

Football and Men’s Basketball Class - all current and former Power 5 (plus Notre Dame) football and men’s basketball players on a full athletic scholarship at any time between June 15, 2016, and the date the class is certified.

Women’s Basketball Class - all current and former Power 5 (plus Notre Dame) women’s basketball players on a full athletic scholarship at any time between June 15, 2016, and the date of class certification.

Additional Sports Class - excluding the two classes above, all current or former college athletes who competed on a Division I athletic team before July 1, 2021 (the date the NCAA Interim NIL Policy went into effect) and who received compensation for the use of their name, image, or likeness between July 1, 2021, and the date of class certification and who competed in the same Division I sport before July 1, 2021.

For the football, men’s basketball, and women’s basketball classes, the June 15, 2016, date is relevant because the “statute of limitations” (the time limit for filing a suit) for federal antitrust suits is four years. The original complaint was filed on June 20th, 2020, which means the class cannot include athletes who competed more than four years prior or June 2016.

The athletes identified three categories of specific damages:

Broadcast NIL (BNIL) damages “which arise out of student-athletes having been deprived of compensation they would have received from conferences for the use of their NIL in broadcasts of FBS football or Division I basketball games in the absence of [NCAA NIL restrictions]” (emphasis added)

Video game damages “which arise out of student-athletes having been deprived of compensation they would have received from video game publishers for the use of their NIL in college football or basketball video games in the absence of [NCAA NIL restrictions]

Third-party NIL damages “which arise out of student-athletes having been deprived of compensation from third parties for their NIL from 2016 to July 1, 2021, when the NIL policy went into effect.”

BNIL Compensation and Allocation Framework for Power 5 Football and Basketball Classes

In her analysis, Judge Wilken walked through the damage allocation framework for BNIL compensation for each damages class recommended by the athletes’ economics experts.

Judge Wilken found that the proposed formula was “sufficiently reliable and capable of supporting a reasonable jury finding that members of the proposed Football and Men’s Basketball Class and the Women’s Basketball Class would have received BNIL compensation in an amount greater than zero in the absence of the challenged [NCAA] rules.”

The formula is complicated (and a bit confusing) and does not offer specific dollar amounts.

Moreover, the experts’ reports that form the basis for Judge Wilkins's analysis have been placed under seal and are not available to the public.

However, with an admitted risk of oversimplification, we can make a reasonable guesstimate of how damages may be calculated. This framework might be used as the basis for a damages settlement.

1. Classwide Injury and Damages Assumptions

The experts assumed:

(a) A market in which conferences and schools were not prohibited from paying class members for their BNIL, but other NCAA rules remained in place, including prohibitions on conferences and schools from paying athletes for their athletic performance (no “pay-for-play”).

(b) In the absence of BNIL restrictions, Power 5 conferences would have competed with each other to attract football and basketball players by offering them BNIL payments “because that would have enabled the conferences to maximize their broadcast revenues.” (emphasis added)

(c) This competition would have led the Power 5 conferences to enter into group-licensing BNIL deals with class members for the use of their NIL.

(d) Under a group-licensing approach, Power 5 conferences would have offered equal payments to individual class members for using their NIL.

2. Compensation Allocation Calculations

As to the sport-specific contracts, Power 5 scholarship athletes in a given conference for a given sport would receive ten percent of the value of any such contract on an annual basis, divided in equal shares among all conference athletes.

For the multisports contracts, the athletes’ experts recommended taking ten percent of the total value of all such contracts and allocating the money according to the following formula by sport:

(1) 75% to football

(2) 15% to men’s basketball

(3) 5% to women’s basketball

(4) 5% to the “Additional Sports” class (non-revenue sports)

These allocations mirror the approximate value of each sport/class in the overall college sports marketplace.

Importantly, within these percentage allocations, each athlete would receive an equal share. Thus, on a football roster with 85 scholarship players (NCAA maximum), the highest-value player receives the same amount as the lowest-valuable player.

In an affidavit supporting the NCAA and Power 5’s opposition to class certification, SEC commissioner Greg Sankey offered a hypothetical payout scenario for a multisport broadcast media contract.

Sankey assumed:

(1) a fourteen-school Power 5 conference

(2) $500 million in total multisport media contracts for one year

(3) equal-share payments

(4) a full allotment of permissible scholarships per sport

Ten percent of $500 million is $50 million. That amount would be allocated across the four certified classes according to the percentage values of each sport/class.

In Sankey’s hypothetical,1,190 football players (85 scholarships maximum X 14 schools) would receive 75% of $50 million, or $37.5 million. This amount would be split in equal shares for a total of $31,513 per football player for that year.

For men’s basketball, 182 players (13 scholarships maximum X 14) would split 15% of the $50 million, or $7.5 million. The equal share distributions would be $41,209 per men’s basketball player. Because of the small number of men’s basketball players, their individual shares are substantially more than the football players’ share.

For women’s basketball, 210 players (15 scholarships maximum X 14) would split 5% of $50 million, or $2.5 million. The equal share distributions would be $11,905 per women’s basketball player for that year.

Assuming that some subset of Power 5 football players would receive allocations of CFP money, their payout may be substantially higher. The same may be true for a subset of Power 5 basketball players with March Madness money.

Group of 5 football and basketball players are not included in the damages classes and, therefore, would not be eligible for distributions.

NCAA Objections and Implications of the Approved Framework

The NCAA raised a slew of objections to the athletes’ compensation framework. A couple are noteworthy.

First, the NCAA argued that in the hypothetical market environment described by the athletes’ experts, schools, not conferences, would compete to offer BNIL group licensing payments to athletes.

The NCAA observed that conferences have never made direct payments to athletes, and it is unreasonable to assume they would have done so in the hypothetical market the athletes’ experts suppose.

The NCAA makes a related point that the athletes’ original suit envisioned BNIL payments by schools, not conferences, and the shift to a conference-based framework is inconsistent with the athletes’ theory of liability.

The court rejected those arguments.

The NCAA also claimed that the athletes’ BNIL compensation framework violates Title IX because most of the money would go to men. The NCAA argued that an antitrust remedy cannot be a violation of other laws.

In rejecting this argument, Judge Wilken made a crucial threshold observation, saying that the NCAA “presupposes that Title IX would apply to the BNIL payments contemplated [by the athletes’ experts], but [the NCAA and Power 5] have not shown that such is the case. As discussed above, those payments would have been made by conferences, not schools, in [the experts’] BNIL but-for world.” (emphasis added)

Indeed, the Power 5 conferences are unlikely to be subject to Title IX requirements because they do not receive federal education funding, a prerequisite to potential Title IX liability.

In NCAA v Smith (1999), the U.S. Supreme Court held that the NCAA was not subject to Title IX requirements because it did not receive federal funding. Although Judge Wilken did not cite Smith, she appeared to use that line of thinking in suggesting payments from conferences would not implicate Title IX.

NCAA’s Emergency Appeal to the Ninth Circuit

On November 17, 2023, the NCAA and Power 5 petitioned the Ninth Circuit for immediate review and reversal of Judge Wilken’s order granting the athletes’ motion for certification of the damages class.

The NCAA renewed its objections from the district court and dramatically portrayed a multi-billion-dollar damage award as not only the “death knell of this litigation” but also for college sports as we know them.

In making this argument, the NCAA openly acknowledged that its business model is premised on the diversion of wealth from profit athletes in Power 5 football and men’s and women’s basketball to interests (including black grants to Divisions II and III) and products that can’t pay for themselves.

In a brief order dated January 18, 2024, the Ninth Circuit denied the NCAA’s petition.

It should be noted that this type of appeal is exceptional and rarely granted. The NCAA can raise these issues again in an appeal after the disposition of the entire case (if it is not settled).

Next Steps in House

The athletes have “run the table” on the preliminary milestones in class action antitrust litigation and have momentum on their side.

The next crucial litigation milestone will come in early April 2024, when the parties file “dispositive” motions before trial. These will include motions for summary judgment, which include evidence accumulated throughout the litigation.

The briefing on these issues will end on July 26, 2024, and the court will hold a hearing on all motions on September 19, 2024.

In ruling on these motions, the court will decide on the merits of issues in the case.

A trial is set for January 27, 2025.

5. Hubbard v NCAA (April 4, 2023; pending)

On April 4, 2023, a group of athletes filed a class action antitrust suit against the NCAA and Power 5 conferences in the Northern District of California before Judge Wilken.

Jeffrey Kessler and Steve Berman again teamed up to represent the athletes.

The suit seeks “back” Alston education benefits (up to $5,980 per athlete) for athletes who were eligible for those benefits (per school criteria) but did not receive them because their schools did not adopt them as soon as they could have.

The district court’s order in Alston permitting those benefits was issued on March 8, 2019, and was upheld on appeal to the Ninth Circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court.

On August 12, 2020, the NCAA adopted a bylaw that permitted FBS athletes to receive the $5,980 benefit.

As noted above, the Alston benefit is permitted but not required.

Plaintiff Chubba Hubbard was an Oklahoma State football player from 2017 - 2021. Throughout his career, his athletic scholarship did not include the Alston benefit, even though Oklahoma State could have offered it for his last two years.

On March 9, 2022, Oklahoma State announced it would begin awarding all scholarship athletes the full Alston benefit of $5,980.

The complaint alleges that “as a direct result of the NCAA rules prohibiting OSU from offering such payments sooner—rules that have since been determined to violate the antitrust laws—Hubbard was deprived of receiving the $5,980 Academic Achievement Award that he would have earned each year he attended OSU.”

Plaintiff Kiera McCarrell, a track and field athlete at the University of Oregon and Auburn University, likewise missed the Alston benefit her first three years because Oregon and Auburn adopted it in her senior year.

The complaint defines the relevant class as:

“All current and former NCAA athletes who competed on a Division I athletic team at any time between April 1, 2019, and the date of class certification who would have met the requirements for receiving an Academic Achievement Award [$5,980 Alston education benefit] under the criteria established by their schools for qualifying for such an award. The class excludes individuals who released their damages claims as part of the Settlement Agreement in In re NCAA Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litigation, No. 14-md-0241-CW (N.D. Cal. Dec. 6, 2017), ECF No. 746.”

There are a few interesting aspects of the suit.

First, because the Alston benefit is not required, a school that chose not to offer it would not be liable under the plaintiff’s theory of the case.

Second, the proposed class excludes athletes whose claims were released in the Alston settlement component (2017), related to full cost of attendance payments. It’s unclear how that settlement ties into Hubbard.

Third, Hubbard is listed as an “associated case” with the House suit in the court docket. The court’s proposed scheduling order (November 3, 2023) fast-tracks the case to align its timing substantially with House. It appears to envision using evidence from House rather than full-blown discovery, and a trial date has been set for December 2, 2024, nearly two months before House.

6. Bewley v NCAA (November 1, 2023; pending)

On November 1, 2023, twin brothers Matthew and Ryan Bewley sued the NCAA in federal court (N.D. Illinois )under a state statute and federal antitrust laws, claiming they were unlawfully denied NCAA eligibility because they received compensation to attend high school at the Overtime Elite Academy (OTE) in Atlanta, Georgia.

The Bewleys sought temporary and permanent injunctions prohibiting the NCAA from enforcing its ineligibility determination.

District court judge Robert Gettleman denied the athletes’ preliminary injunctive relief claims by order dated January 10, 2024.

Importantly, Judge Kettleman pointed to the viability and legitimacy of the NCAA’s no-pay-for-play rules despite the Supreme Court’s unanimous Alston decision in June 2021.

7. Fontenot v NCAA (November 20, 2023; pending) and Carter v. NCAA (December 7, 2023; pending)

Fontenot and Carter should be viewed as companion cases because they seek the same outcome: the elimination of all NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits. Importantly, as discussed below, the parties have been engaged in complex procedural maneuvers to consolidate the cases in the same court.

These consolidation attempts have crucial implications for the prospects of a global settlement that would include House, Hubbard, Fontenot, and Carter.

a. Fontenot

On November 20, 2023, former University of Colorado football player Alex Fontenot filed a federal class action antitrust suit against the NCAA in Colorado, claiming that all NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits violate federal antitrust laws.

Fontenot is virtually identical in purpose to the original Jenkins/Alston suit filed in 2014.

The suit seeks damages and injunctive relief.

The proposed class includes “All persons who worked as full athletic-scholarship athletes in football, men’s basketball, or women’s basketball at an NCAA Division I school that is a member of one of the Power Five Conferences or at the University of Notre Dame…from the beginning of the statute of limitations period…through judgment in this matter.”

Importantly, the law firm Korein Tillery represents the athletes, not the Kessler or Berman firms, which represent the athlete classes in House, Hubbard, and Carter.

b. Carter

On December 7, 2023, another group of athletes filed a class action antitrust suit—Carter v NCAA—against the NCAA and Power 5 conferences in the Northern District of California.

As noted, Kessler and Berman represent the Carter athletes.

Like Fontenot, Carter replicates the original Jenkins/Alston claims, which sought to strike down all NCAA amateurism-based compensation and eligibility limits and rules, not just a subset of those rules.

The class representatives are DeWayne Carter, a Duke University football player, and Sedona Prince, a TCU women’s basketball player (formerly University of Oregon).

The injunction relief class is comprised of “All student-athletes who compete on, or competed on, a Division I athletic time between December 7, 2023, and the date of judgment in this matter.”

The damages class is comprised of “All current and former student-athletes who compete on or competed on, a P5 Conference or Notre Dame basketball or football team at any time between December 7, 2019, and the date of judgment in this matter. This class excludes any athletes who competed for their school prior to March 21, 2017, and are bound by the class settlement releases in re: NCAA Athlete Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litigation.”

The complaint also makes a preemptive case against many of the NCAA’s justifications for its amateurism-based compensation limits, including the sky is falling narrative that payments to profit athletes in Power 5 football and men’s/women’s basketball will “drain cross-subsidies to non-revenue sports.”

An interesting aspect of Carter is that the case is not assigned to Judge Wilken. Instead, Northern District Judge Richard Seeborg has the case.

There was some initial confusion about the case assignment. A magistrate judge initially assigned it to Judge Seeborg, then reassigned it to Judge Wilken as a case “related” to House and Hubbard, and then assigned it back again to Judge Seeborg

c. Procedural Fight for Control

Right after the filing of Carter, Kessler took a proactive stance, advocating for a global settlement of House, Hubbard, and Carter. In a podcast interview with Tulane law professor Gabe Feldman on December 8, 2023, the day after Carter was filed, Kessler addressed the global settlement:

Kessler: I think the one thing that might help [the NCAA] with Congress in the future is reaching an antitrust settlement with us…because if the antitrust claims are resolved and approved by the court as fair and reasonable to the classes, both the past damages and the going forward, then it's much easier for Congress to think about the rest of it, right?

Feldman: That's why, to me, the Baker proposal, if you consider a multi-step process to get a settlement, which is difficult with all the different lawsuits out there and the employment cases, but if it's, we will provide a better system going forward, that's more fair—and you may disagree with say we need more detail before we'd ever agree to that—but also is damages for the last six years or whatever the number is, and then if you package that together as a global settlement to bring to Congress to say, we now as the plaintiffs are on board with this, then you start to see a path to say, we're not going to be in this sort of limbo where we're going to get sued constantly.

Kessler: I think if they settled with us, that would be a great step…for the athletes and everyone else going forward in all different ways.

In January 2024, the parties in Fontenot and Carter began a series of opposing procedural maneuvers to consolidate the two cases in either Colorado (Fontenot) or California (Carter).

The Carter attorneys and NCAA/Power 5 joined forces to have Fontenot moved from Colorado to California and prevent Carter from being moved to Colorado.

They have employed two different pathways: (1) the U.S. Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation (MDLP) and (2) a more traditional motion to transfer under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Both pathways are designed to coordinate related cases across federal districts, ostensibly to promote judicial efficiency, convenience, and consistent outcomes.

On January 9, 2024, the Carter attorneys filed a request to transfer with the MDLP to move Fontenot to California.

On April 11, 2024, the MDLP denied the Cater athletes’ request, finding that “centralization is not necessary for the convenience of the parties and witnesses or to further the just and efficient conduct of the litigation.”

Around the same time, on February 7, 2024, the Fontenot athletes filed a motion to intervene in the Carter suit to file a motion to transfer Carter to Colorado under traditional transfer rules.

By order dated April 29, 2024, the district court judge in Carter permitted the Fontenot athletes to intervene but denied their motion to transfer, relying on the Northern District of California’s long-standing history with athlete compensation and benefits lawsuits (e.g., O’Bannon, Alston, House).

To add to the confusion, as the Carter court was deliberating on the Fontenot athletes’ motion to transfer Carter to Colorado, the NCAA and Power 5 filed a traditional motion to transfer in Fontenot, asking the district court judge there to move Fontenot to California.

All of this aggressive procedural activity raises the question: why is it so important for the Carter athletes and the NCAA/P5 to have Fontenot moved to California?

Why do they desperately seek to have House, Hubbard, Fontenot, and Carter all in the Northern District of California?

The briefing on the NCAA/P5’s motion to transfer in Fontenot provides some important clues.

In their brief opposing the NCAA/P5’s motion to transfer, the Fontenot attorneys suggest cooperation between the athletes’ attorneys in House and Carter and the NCAA/P5 to sweep Fontenot into a potential global settlement of House, Carter (and Hubbard).

The Fontenot athletes observe that “Media reports indicate that [the NCAA/P5] are discussing a broad potential settlement with counsel for Carter/House. Given the money involved, counsel for Carter/House may be incentivized to settle both cases at once despite the obvious conflicts that would arise when trying to do so. This case should remain separate to ensure Fontenot is not consolidated with Carter, which will in turn ensure adequate and unconflicted representation of Fontenot class members.”

The Fontenot attorneys also note the irony of the NCAA/P5 abandoning their fifteen-year-long criticism of the Northern District of California and District Court Judge Claudia Wilken as biased against the NCAA, saying “[a]ll of this may explain why [the NCAA/P5] seek to transfer this case to California after trying to avoid the state for over a decade.”

If the Carter athletes and the NCAA/P5 succeed in their joint effort to consolidate Fontenot with Carter in California, the district court judge in Carter would then have the discretion to name the Kessler-Breman firms as class counsel for the Fontenot athletes. This would result in the Kessler-Berman team co-opting the Fontenot litigation and rolling it into a pre-bargained settlement completely outside the control of the Fontenot athletes and attorneys.

8. Ohio et al. v NCAA (pending)

On December 7, 2023, the states of Ohio, Colorado, Illinois, New York, North Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia filed a federal antitrust suit against the NCAA, challenging the NCAA’s one-time transfer rule as a violation of antitrust laws.

The suit sought temporary and preliminary injunctions preventing the NCAA from enforcing its one-time transfer rules for athletes who sought a second transfer.

The court granted the states’ request for a temporary restraining order, after which the NCAA agreed to a stipulation that it would not enforce the one-time rule during the 2023-2024 season. A hearing on the states’ preliminary injunction will be held after the spring season.

On the same day, a University of West Virginia men’s basketball transfer, ReaQuan Battle, filed a federal antitrust lawsuit against the NCAA challenging the one-time transfer rule. Battle also brought state-based claims for tortious interference with contract and breach of contract.

On January 18, 2024, the states of Virginia, Minnesota, and the District of Columbia joined the suit as plaintiffs. Importantly, the United States also joined the suit.

The Ohio case is an important inflection point because it marks the first coordinated effort by state attorneys general and the United States to challenge NCAA eligibility rules.

However, the case also provides the NCAA with a pathway to a negotiated settlement on injunctive relief, which will provide the NCAA with legal protection going forward.

9. Tennessee v NCAA (pending)

On January 18, 2024, the states of Tennessee and Virginia filed a federal antitrust case against the NCAA challenging NCAA NIL-related rules, policies, and guidelines prohibiting third parties (boosters and collectives) affiliated with a school from discussing NIL opportunities with high school and transfer portal prospects.

In essence, the Tennessee suit is a NIL recruiting inducement case. It arose from the University of Tennessee’s concerns that the NCAA may bring an enforcement action against Tennessee because of contacts its NIL collective had with football recruits.

The states seek temporary, preliminary, and permanent injunctive relief prohibiting the NCAA from enforcing its NIL recruiting inducement prohibition.

a. Temporary Injunction

On February 6, 2024, the court denied the states’ request for a temporary restraining order, finding they would not suffer “irreparable harm” if the restraining order was not granted.

The court also observed that any harm the states (and athletes) may suffer could be remedied through monetary damages such as those that might result from the House litigation.

Importantly, the states’ rely in part of their state NIL laws, arguing that the NCAA’s enforcement of its recruiting inducement rules and policies would undermine athletes ability to fully pursue NIL opportunities in accordance with the state laws.

However, the Tennessee NIL law explicitly prohibits the use of NIL as a recruiting inducement.

b. Preliminary Injunction

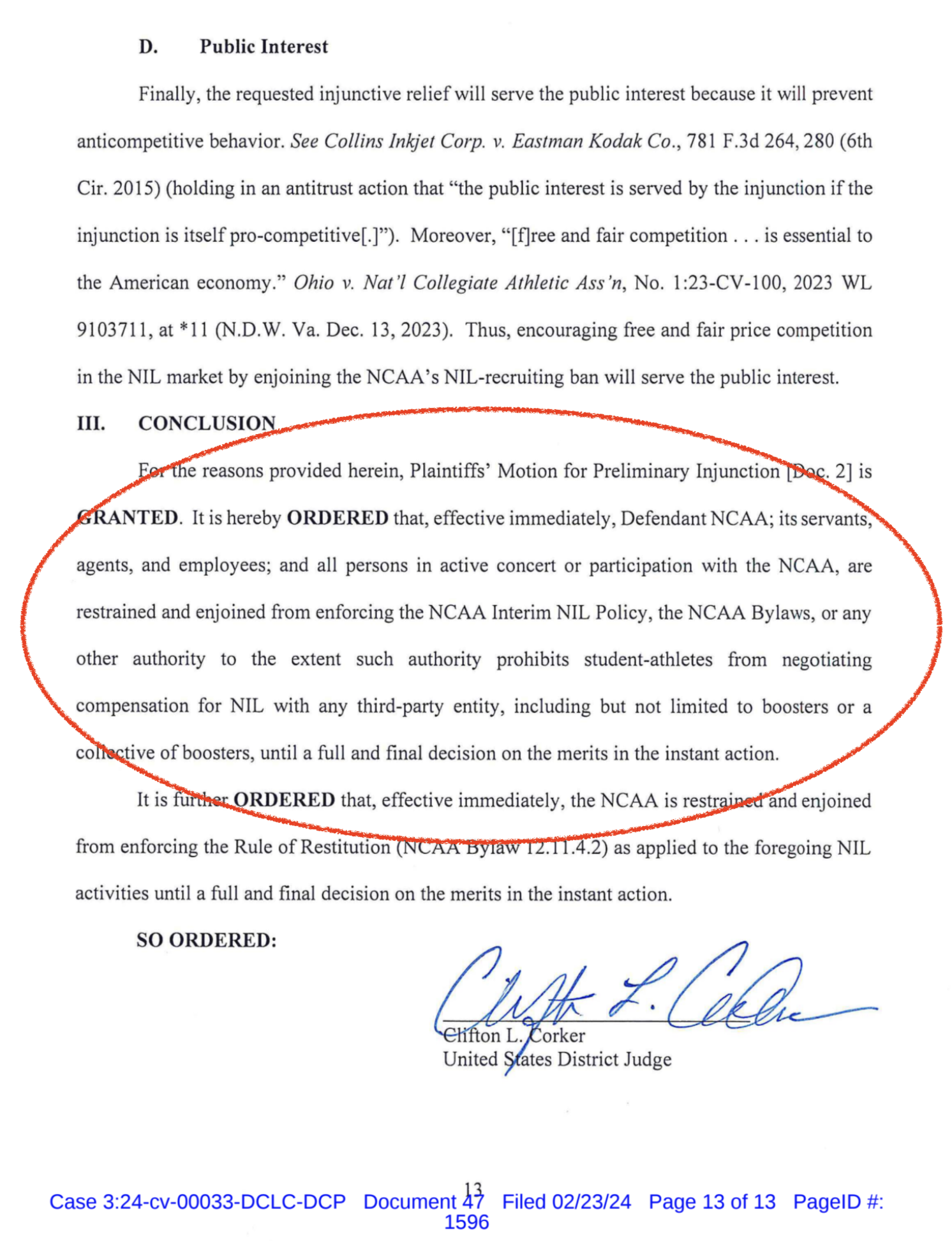

On February 23, 2024, the federal district court judge overseeing the case issued a preliminary injunction against the NCAA, prohibiting it from enforcing the NCAA’s NIL-related no-negotiation rule with respect to third parties such as boosters or collectives.

The ruling has been hailed in the media as a crucial move away from amateurism-based principles and regulation.

However, the ruling was very narrow.

The injunction does not disturb prohibitions on play for play (from any source) or pay by a university to induce an athlete to attend their institution.

The injunction applies only to NIL prohibitions that prevent “student-athletes from negotiating compensation for NIL with any third-party entity, including but not limited to boosters of a collective of boosters…” (emphasis added)

c. Institutional Interests Over Athlete Interests

Importantly, both the Ohio and Tennessee suits were driven in whole or part by competitive advantage/disadvantage concerns in the talent acquisition market. Each suit sought to meet the schools' short-term labor needs.

While states have wrapped their legal arguments around free markets and concerns for athletes’ rights, the relief they seek serves mainly institutional purposes to field successful, profitable football and men’s basketball teams.

In its motion for a preliminary injunction in the NIL suit, Tennessee argued that a threatened NCAA infractions case against the University of Tennessee for alleged violations of NCAA’s NIL policies would harm the state’s “quasi-sovereign interest in the economic well-being of their residents in general.”

Tennessee also claimed the NIL recruiting ban “hinders recruiting and that schools accused of violating the ban lose players, scholarships, and post-season opportunities, which decreases competitiveness and fan interest” and that “no damages could replace players lost, reputations harmed, games not played, or championships not won.”

These are undeniably institutional interests that overshadow athlete interests.

Any benefit to athletes is purely incidental to that purpose and the product of temporary interest convergence.

Observations from the Antitrust Cases