IV. Who Gets to Decide?

In the eyes of college sports’ power brokers, the most critical question facing college sports in 2024 and beyond isn’t only whether or how much athletes are paid or whether certain athletes may become employees of their university but who has the authority to decide.

Who gets to make the rules, interpret the rules, and enforce the rules?

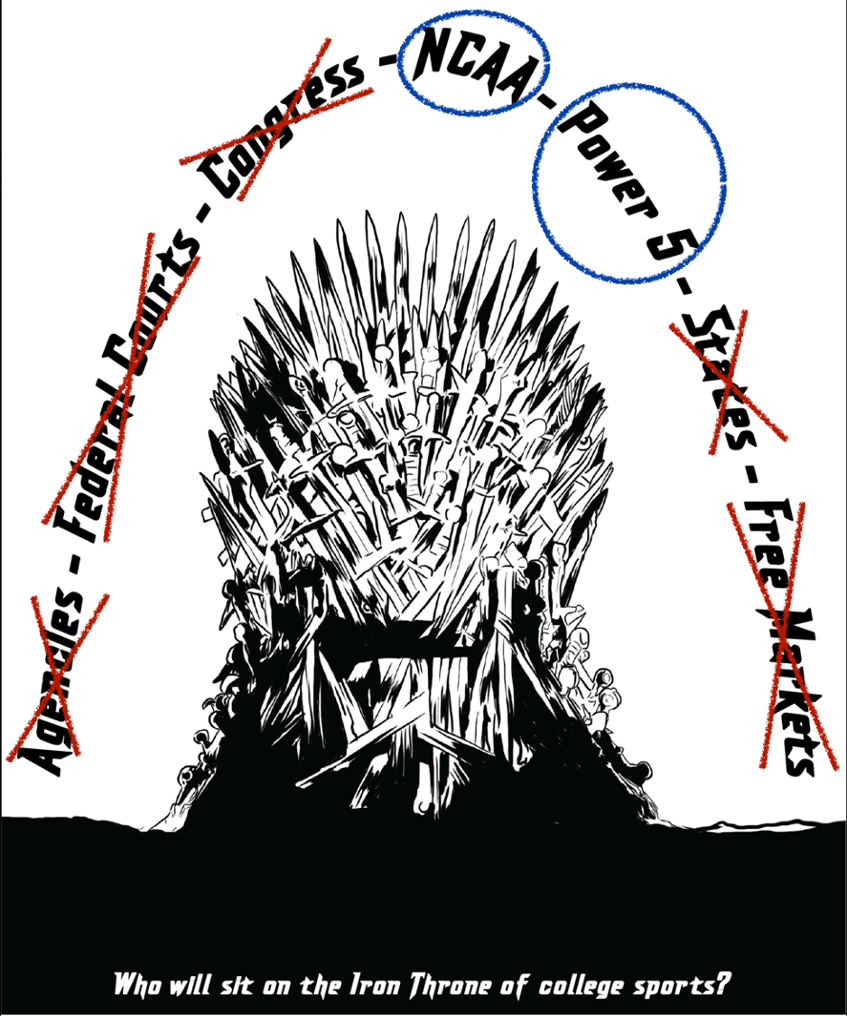

The NCAA and Power 5 believe that they, and they alone, should sit on the Iron Throne of college sports regulation with unchallengeable authority.

The NCAA’s and Power 5’s campaign in Congress is driven by that singular quest—the ruthless elimination of any competitors to their regulatory supremacy.

Historically, the NCAA would deal with occasional threats to their power without a comprehensive strategy.

The NCAA successfully beat back these one-off threats, dealing with each in isolation. In essence, the NCAA used a “whac-a-mole” strategy to eliminate outside (and largely symbolic) interference with its regulatory authority.

However, things began to change in the 21st century when, in the face of NCAA inaction on athlete benefits and protections, athletes turned to multiple external regulators to force the NCAA to change.

I. External Regulatory Pressures Mount

External regulatory pressure has come through four main pathways: (1) federal courts, (2) federal administrative agencies, (3) state legislatures, and now, (4) free markets.

NOTE: A detailed analysis of the roles of federal courts, federal administrative agencies, state legislatures, and free markets can be found in the corresponding Tabs in the Explore menu on our gateway page.

A. Federal Courts

In the 21st century, federal courts have played a pivotal role in college sports.

Class action antitrust suits filed by athletes directly challenging NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits have led to modest changes in athlete benefit packages and forced the NCAA and Power 5 to do things they don’t want to.

However, these cases have also benefitted the NCAA and Power 5 because legal principles from these cases are largely favorable to NCAA and Power 5 interests and shield them from an open labor market—”pay-for-play”— for athletes’ services.

Below is a brief overview of key class action cases that have influenced, or may influence, the relationship between athletes and institutions.

White v NCAA (2006-2008)

In 2006, a group of athletes sued the NCAA under federal antitrust laws challenging the NCAA’s athletic scholarship set below the full cost of attending college. The athletes argued the athletic scholarship should include the full cost of attendance “stipend” (FCOA), a modest additional subsidy (approximately $2,000 - $5,000 per athlete per year) to cover miscellaneous living costs.

From 1956 – 1975, the athletics scholarship included a similar stipend known as “laundry money.”

However, in 1975, the NCAA eliminated laundry money as a claimed cost savings measure.

Many in the media and college sports commentariat portrayed White as an existential threat to the amateurism-based regulatory model.

White was to be the case that would bring down the NCAA’s core principle of amateurism.

In White and public pronouncements, the NCAA aggressively opposed the FCOA stipend not because it cost too much but because it would violate the NCAA’s principles of amateurism and transform college athletes from amateurs into professionals.

In a 2006 talk at the National Press Club, former NCAA President Myles Brand emphatically said that FCOA stipends are pay-for-play and violate the NCAA’s core principles.

In 2008, the NCAA settled White for a pittance.

The NCAA retained its scholarship limit set below the FCOA and continued its opposition.

However, White signaled a new and potent threat to the NCAA’s and Power 5’s hegemony: class-action federal antitrust suits directly challenging NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits.

O’Bannon v NCAA (2009 - 2016)

In 2009, a group of athletes sued the NCAA in California under federal antitrust laws challenging the NCAA’s amateurism-based compensation limits on name, image, and likeness (NIL).

Like White, O’Bannon was characterized by many as the case that would finally crack the dam on the NCAA’s principle of amateurism.

After a full bench trial in 2014, a U.S. District Court judge held that the NCAA’s NIL compensation limits violated federal antitrust laws and ordered nominal NIL trust funds ($5,000 per athlete per year) and the FCOA stipend as permissive remedies.

In 2015, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals struck down the trust funds as inconsistent with amateurism but allowed the FCOA stipend.

Importantly, the 9th Circuit drew an amateurism-based distinction between education-related benefits, which were permissible, and non-education benefits (pay-for-play), which were impermissible.

This crucial limitation meant that O’Bannon was as much a victory for the NCAA as for the athletes.

The 9th Circuit’s deference to amateurism eliminated the possibility that athletes could receive compensation for the full value of their athletics services. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case in 2016.

Despite O’Bannon’s limitations and the 9th Circuit’s deference to amateurism, the case was important for another reason: a federal circuit court rejected the NCAA’s claim for absolute and explicit judicially created antitrust immunity as a matter of law.

After O’Bannon, the NCAA was required to defend its anticompetitive practices under well-settled antitrust legal tests that apply to all other industries and market participants.

Alston v. NCAA (2014 - 2021)

As the district court phase of O’Bannon was winding down in 2014, two other groups of athletes filed class action antitrust suits challenging NCAA compensation limits—Alston v NCAA in California and Jenkins v NCAA in New Jersey. The cases were consolidated (into “In re: NCAA Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litigation”) and became known to the public as “Alston.”

The Alston athletes challenged all NCAA compensation limits.

As with White and O’Bannon, many portrayed Alston as the case that would finally bring the NCAA’s amateurism-based regulatory model to its knees and its senses, resulting in an open and free market for the full value of athletes’ services.

However, because Alston was filed in the same federal circuit as O’Bannon, the O’Bannon decision was a binding precedent.

Ultimately, Alston was whittled down to education benefits to conform to O’Bannon’s amateurism-based education-noneducation framework.

The district court in Alston found that the NCAA’s limitations on education benefits violated antitrust laws and permitted (but did not require) a narrow set of education benefits.

The NCAA appealed to the 9th Circuit (where it lost) and then to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Importantly, on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, the athletes chose not to pursue their original claims that all NCAA compensation limits should be declared a violation of antitrust laws.

Instead, they chose to seek only the affirmance of the district court’s limited injunction and its modest, permissive education benefits.

The limited education benefits posed no financial harm to the NCAA and Power 5.

Why did the NCAA and Power 5 appeal Alston to the U.S. Supreme Court?

Because they sought a judicially created amateurism-based antitrust immunity on the theory that as the guardians of the sacred principle of amateurism, they were literally above America’s free competition laws.

On June 21st, 2021, the Supreme Court issued a 9-0 decision, refusing to grant the NCAA antitrust immunity. The ruling was a powerful but largely symbolic blow to the NCAA’s conceptualization of amateurism.

The Supreme Court merely affirmed the lower courts’ rulings permitting the limited set of education-related benefits.

Because of the way the athletes framed the case, the Court did not have to decide whether all NCAA amateurism-based restrictions violate antitrust laws.

Johnson v NCAA (2019 - present)

In 2019, a group of athletes filed a federal class action suit claiming entitlement to hourly wages under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). To be covered by the FLSA, a worker must establish they are employees within the meaning of the Act.

The employee status question is unresolved.

House v NCAA (2020 - present)

In 2020, while Alston was pending, another group of athletes filed a federal antitrust suit seeking additional NIL benefits.

House is a potent threat to the NCAA because the damages have been estimated to exceed $1 billion. In federal antitrust cases, an award of damages is automatically tripled.

House has passed through the early significant class action milestones, including approval of the athletes’ damages class, and is scheduled for trial in January 2025.

As the case now sits, the NCAA and Power 5 have powerful incentives to settle the damages component.

Hubbard (2023), Carter (2023), Ohio (2023), and Tennessee (2024)

In 2023, athletes filed two other class action federal antitrust suits.

One—Hubbard v NCAA (April 4, 2023)—seeks “back” Alston education benefits.

The other—Carter v NCAA (December 7, 2023)—seeks to dismantle all NCAA compensation limits.

The same attorneys represent the athletes In House, Hubbard, and Carter.

On December 7, 2023, a group of states filed a federal antitrust case against the NCAA—Ohio et al. v NCAA— challenging the NCAA’s one-time transfer limitations.

The United States intervened in the suit on January 18, 2024.

On January 31, 2024, the States of Tennessee and Virginia filed a federal antitrust suit against the NCAA, challenging the NCAA’s NIL rules and policies in the context of recruiting inducements.

B. Federal Administrative Agencies

In 2014, a federal administrative agency action directly challenged the NCAA’s concept of the “student-athlete.” Northwestern University football players filed a petition with the National Labor Relations Board (under the National Labor Relations Act) to form a union.

However, only employees have the protections of the NLRA. Thus, the NLRB first had to determine whether Northwestern players met the definition of employee.

After a full evidentiary hearing, the NLRB Regional Director determined, as a matter of fact, that the players were indeed employees.

On appeal, the National NLRB declined to assert jurisdiction for prudential reasons but did not overturn the factual determination that Northwestern football players were employees.

On September 29, 2021, the NLRA’s General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo issued a policy interpretation saying that classifying scholarship athletes as “student-athletes” rather than employees was an independent violation of the NLRA.

In framing the issues, she leaned into the Regional Director’s decision in Northwestern.

She also opined that the NCAA (and conferences) may be liable as “joint employers” with universities.

On February 8, 2022, an athletes’ rights association filed a “misclassification” and “joint employer” charge on behalf of University of Southern California football and men’s/women’s basketball athletes against the USC, the Pac-12, and the NCAA.

The case is moving through the NLRB process.

On September 13, 2023, the Dartmouth men’s basketball team filed a petition in the NLRB seeking employee status and the right to form a union.

On February 5, 2024, the NLRB Regional Director issued her Decision and Direction of Election ruling in favor of the basketball players, finding they met the common law definition of an employee within the meaning of the NLRA.

Athletes have used other administrative agencies, including the Department of Justice’s Office of Civil Rights and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, to pursue and protect their rights.

C. State Legislatures

In 2019, in response to what many viewed as a disappointing outcome in O’Bannon, the California state legislature began discussing—and ultimately enacted—a state NIL law (SB 206) that would offer athletes in California meaningful NIL rights.

The NCAA initially responded to SB 206 with the same strident opposition to NIL it demonstrated throughout the O’Bannon litigation. Indeed, the NCAA threatened a federal lawsuit against California to nullify SB 206.

SB 206 led to a wave of state NIL laws that would become the NCAA’s and Power 5’s justification to ask Congress for breathtaking federal protections and immunities to protect the NCAA’s regulatory authority and eligibility rules, notably including its amateurism-based compensation limits.

D. Free Markets

In late June 2021, after losing its last-ditch attempt in the Senate for a federal bill that would eliminate state name, image, and likeness laws (through federal preemption; see preemption section below), the NCAA was forced to temporarily fall on its sword on NIL with the announcement of the “Interim Policy.”

The Interim Policy was a stopgap measure until the NCAA obtained protective federal legislation allowing it to regulate the NIL market without legal accountability.

The Interim Policy has permitted some free market dynamics to benefit athletes in the college sports ecosystem.

Perhaps more than any other form of external regulatory pressure, free markets have exposed the NCAA and Power 5’s anti-NIL fearmongering campaign as a sham.

A less-regulated NIL market has not resulted in the fatal collapse of college sports as we know them, the mass extinction of women’s and Olympic sports programs, or reduced consumer demand for the most professionalized products in college sports (Power 5 football and men’s/women’s basketball).

On the contrary, the college sports marketplace is growing at a breathtaking pace. Money is falling from the sky for the Power 5 through historic media rights deals, the expansion of the College Football Playoff, and the introduction of new markets (sports betting products and AI-generated fan engagement platform).

The longer free market forces are in place, the more difficult it will be for the NCAA and Power 5 to argue that athletes should be relegated to second-class citizen status through federal legislation eliminating or substantially limiting their basic economic rights.

II. From Wac-a-Mole to Comprehensive Strategy: The NCAA and Power 5 Go on Offense

On May 14th, 2019, in response to SB 206 (and a federal NIL bill introduced by Rep. Mark Walker [R-NC] in March 2019), the NCAA Board of Governors formed the NCAA Board of Governors Federal and State Legislation Working Group (Working Group).

The Working Group’s initial charge was to decide whether the NCAA should continue opposing NIL “compensation” or explore voluntary NCAA rules changes to permit NIL payments.

With the assistance of the best legal, lobbying, and public relations experts in Washington, D.C., the NCAA crafted a cynical campaign to do both.

The Working Group led athletes and stakeholders to believe the NCAA would voluntarily offer NIL “compensation” by January 21st, 2021. However, simultaneously, it embarked on a campaign in Congress for protective federal legislation that would give it the authority to do nothing on NIL.

In response to external regulatory threats, the NCAA ditched its historical “whack a mole” defensive strategy and went on offense.

Beginning in February 2020, NCAA-friendly Senators began conducting hearings that laid the foundation for bills that would give the NCAA and Power 5 absolute regulatory authority and federalize NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits.

Specifically, the NCAA and Power 5 sought from Congress (1) antitrust immunity to eliminate federal courts from the regulatory field, (2) federal preemption of state laws that conflict with NCAA regulatory authority and compensation limits to eliminate state legislatures, and (3) a provision that athletes cannot be employees of their university making it impossible for athletes to seek the benefit of federal labor laws (e.g., National Labor Relations Act and Fair Labor Standards Act) that require employee status.

Through this process, a number of NCAA/Power 5-friendly bills emerged, many affording the NCAA preemption, antitrust immunity, and non-employment status for athletes.

Importantly, on the question of “who gets to decide,” many of the NCAA/Power 5-friendly bills would create a federal commission, corporation, or office of an existing federal agency to regulate college sports.

The eligibility criteria for governing board seats on these entities would result in NCAA and Power 5 insiders dominating the decision-making process.

In essence, these bills would replicate the NCAA and Power 5 bureaucracies.

These three protections and immunities would eliminate the most potent external regulatory threats to the NCAA and Power 5 in one fell swoop.

A. Antitrust Immunity

The NCAA and Power 5 seek an exemption from America’s federal free competition (“antitrust”) laws that would allow them to impose their amateurism-based compensation limits without legal consequence.

This is an exceptional ask.

There are four ways the NCAA and Power 5 can attempt to achieve some form of antitrust immunity:

(1) Congressional antitrust immunity, which the NCAA and Power 5 have sought since 2019.

(2) Judicially created antitrust immunity through final rulings and binding legal precedent, which the NCAA and Power 5 partially obtained in O’Bannon but failed to fully obtain in Alston.

(3) Settlement-based antitrust immunity through which the NCAA and Power 5 essentially “purchase” immunity by settling class action antitrust cases in whole or part and receiving in return broad releases from past, current, or future liability for the anticompetitive practice at issue.

(4) Collective bargaining immunity under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), through which the NCAA and Power 5 would receive what’s known as non-statutory collective bargaining antitrust immunity. The NCAA and Power 5 have steadfastly refused to consider this immunity pathway because it would occur in a setting where the NCAA and Power 5 would have to recognize athletes as employees.

While the Supreme Court in Alston turned away the NCAA’s quest for judicially created antitrust immunity, the NCAA and Power 5 aggressively sought and continue to seek similar immunity from Congress or potentially through “omnibus” settlements of the pending compensation-related antitrust cases (House, Hubbard, and Carter) that would provide the NCAA and Power 5 with sweeping releases from past, present, and future antitrust liability.

B. Preemption of State Laws

The NCAA and Power 5 seek to eliminate all state laws that (1) permit any form of compensation to athletes, including, but not limited to, NIL, or (2) conflict with other NCAA eligibility rules.

Preemption is an extraordinary constitutional power (Article VI “Supremacy Clause”) that disrupts the carefully calibrated constitutional balance of power between the federal government and states.

Congress has used preemption to ensure that our most vital national interests—national security, civil rights, nuclear safety, environment, air travel safety, drug approval/testing/labeling, toxic waste, toxic product warnings, and disclosures— are protected without conflicting state requirements.

The NCAA and P5 want Congress to invoke this authority to protect the commercial interests of private, nonprofit associations

C. Athletes Can’t Be Employees

The NCAA and Power 5 also seek a declaration from Congress that athletes cannot, as a matter of federal law, be employees of their universities.

This is a breathtaking request that has little to do with NIL.

By its very definition, the NIL market operates only between athletes and third parties. Schools are prohibited from paying athletes directly for NIL deals.

Only direct NIL payments from schools to athletes could trigger employee status.

Why do the NCAA and Power 5 seek a no-employee bill from Congress?

Because an athlete must be an employee to engage in collective bargaining under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) or benefit from other employee protections under other federal and state labor laws.

As the congressional hearings have evolved since February 2020, the NCAA, Power 5, and their lobbyists have increasingly emphasized the no-employee plank of their overall strategy to eliminate external regulatory threats.

During a hearing in the House on January 18, 2024, the no-employee issue dominated the hearing.

Including the no-employee limitation in NCAA-friendly “NIL” bill proposals proves the NCAA’s/P5’s use of “NIL compensation” as a Trojan Horse for sweeping federal protections and immunities.

As illustrated in the Iron Throne graphic below, if the NCAA and Power 5 receive these three federal protections and immunities, they would—quite literally—be placed above the law.

They could impose their athlete compensation limits and eligibility rules without any legal consequences, accountability, or interference by external regulators.

These protections and immunities would end the athletes’ rights movement and permanently return the NCAA/Power 5 regulatory authority to the Red Ball position in the Pendulum metaphor as a matter of federal law.

Athletes, particularly Power 5 football and men’s basketball athletes —whose labor fuels the entire college sports industrial complex—would become second-class citizens.

III. The NCAA’s and Power 5’s Cynical Strategies in Congress and Public Relations

The NCAA and Power 5 have constructed a web of self-serving and often divisive narratives to maintain control of college sports regulation's Iron Throne.

The NCAA’s and Power 5’s tactics align with the playbooks of other behemoth “Bigs,” such as Big Pharma, Big Tobacco, Big Data, and Big Gambling.

The NCAA employs the #1 ranked lobbying firm in Washington DC, Brownstein Hyatt. So, too, does Purdue Pharma, the public face of America’s opioid crisis.

Individual lobbyists representing Purdue also represent the NCAA.

The nature of this lobbying activity suggests a “crisis” philosophy. Several of the NCAA’s lobbyists are experts in “crisis management.”

We know what Purdue’s crisis is—misleading the medical community, patients, and the public on the addictive nature of opioid products.

What is the NCAA’s “crisis”?

Having to comply with America’s foundational free competition and labor laws.

We are not criticizing the lobbying firms or the individual lobbyists. They are doing their jobs and are very good at them.

But isn’t it fair to ask why the NCAA sees its interests and tactics in Congress through the same lens as Big Pharma?

Operating in crisis mode, no tactic or narrative is off-limits for the NCAA.

A. NCAA Chaos Theory: The Summer of 2021 (Alston, NIL, and Transfer)

Athlete victories in the summer of 2021 resulted in some changes to the status quo business model.

However, the NCAA and Power 5 have portrayed these new market features as “Wild West” chaos that is spiraling college sports towards extinction.

Hyperbolic (often inaccurate) coverage of the Alston decision led many to believe the Supreme Court “struck down” amateurism.

However, as noted above, after seven years of contentious and costly litigation ($300 million in legal fees and settlements), the athletes’ “victory” amounted to two things: (1) a definitive legal statement that the NCAA and Power 5 must comply with America’s free competition laws; and (2) the possibility of limited education benefits up to $5,980.

The new NIL and transfer markets are a welcome change in college sports, but it is difficult to assess their true impact because little verifiable data has been collected and analyzed.

Moon landing headlines shape our perception of the NIL marketplace—based largely on rumor and speculation—on outlier deals allegedly worth millions of dollars.

NIL valuations are based on social media followings that may not translate into real dollars.

Institutions refuse to release data on athlete NIL deals in their quest for a competitive advantage in recruiting.

On October 17th, 2023, NCAA President Charlie Baker testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

In one of the most telling comments through four years of congressional hearings on college sports, Baker admitted that “nobody knows what’s going on” in the NIL marketplace because we don’t have any reliable data.

Baker testified that “everything is sort of a guess and a rumor.”

While Baker made his comments in the context of gender equity, Title IX, and the NCAA’s desire—in the name of “transparency”—to collect data on NIL activity to determine “fair market value” for NIL deals, he nevertheless sat behind a microphone in Congress asking for sweeping federal protections and immunities before any fact-finding occurs.

Baker’s testimony exposes fundamental and alarming flaws in the NCAA’s quest for federal protections and immunities.

Baker openly admits that neither the NCAA nor Congress have done any fact-finding on one of the central issues the NCAA and Power 5 have used to thwart progress for all athletes: the unproven assertion that female athletes are being harmed in the current NIL market.

Mr. Baker is content to operate in a fact-free zone on this issue while indulging the NCAA’s presumption of harm to female athletes. Mr. Baker becomes interested in the facts when that presumption is challenged.

Baker has not had the same concerns about the absence of fact-finding on issues such as athletes as employees, athlete health and safety, the NCAA’s refusal to comply with free competition laws, the civil rights implications of the current business model, and, importantly, the NCAA’s historic indifference to true gender equity and Title IX.

In lieu of fact-finding on those issues, the NCAA and Power 5 rely on college sports’ traditions and mythologies, such as amateurism, the student-athlete, and the collegiate model, to obscure the truth of the business mode and prevent substantive discussion.

Similarly, reliable data on the new transfer market needs to be collected. While estimating the total number of transfers is possible, there needs to be more discussion and data on why athletes transfer.

The NCAA and Power 5 want people to believe the transfer market is open free agency, and combined with NIL inducements, leads to athlete disloyalty and foul play by competitors.

Lost in that fearmongering is the reality that free agency in the coaching and conference consolidation markets—and open poaching in both—may be the main culprits in athletes’ decisions to transfer.

The NCAA’s and Power 5’s ongoing criticism of the NIL and transfer markets creates the perception of a “crisis” that only Congress can solve.

B. Reverse Progress Before It Has a Chance

While some institutional stakeholders publicly applaud changes in athlete benefits resulting from antitrust litigation and the new NIL and transfer markets, the NCAA and Power 5 continue their march on Congress, working tirelessly behind the scenes through their lawyers and lobbyists to reverse these gains and restore the status quo that existed before the summer of 2021.

Since 2019, when the NCAA and Power 5 engaged Congress under the guise of NIL compensation to eliminate athletes’ fundamental rights as Americans, over twenty bill proposals that impact athlete interests have been put forth.

Most of them—even those portrayed as athlete-friendly—align to one degree or another with the NCAA’s and Power 5’s amateurism-based values.

In discussions over “reform” in college sports, potential external regulators and decision-makers are magnetically drawn back to the NCAA’s core values.

In the wake of the NCAA’s Interim Policy on NIL that went into effect on July 1st, 2021, six NCAA and Power 5-friendly bills or discussion drafts have been introduced in Congress that would substantially limit the new NIL and transfer markets.

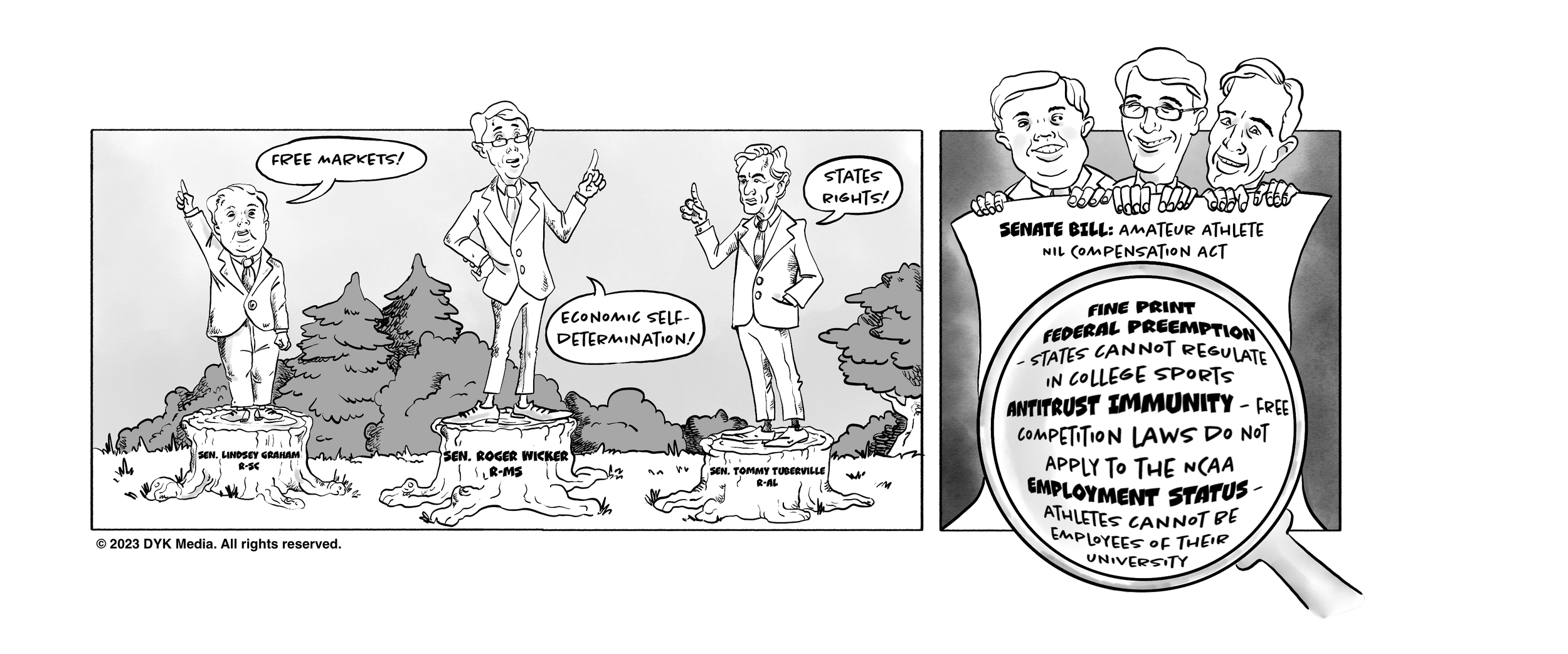

Sponsors of these regressive bills include Sens. Lindsey Graham (R-SC), Tommy Tuberville (R-AL), Roger Wicker (R-MS), Joe Manchin (D-WV), Ted Cruz (R-TX), and Representatives Gus Bilirakis (R-FL), Mike Carey (R-OH), and Greg Landsman (R-OH).

A number of these bills would create a federal entity to act as the policymaking and enforcement arm. Those federal entities would be governed by boards with a majority of NCAA/Power 5 insiders.

These bills would replicate the NCAA/Power 5 regulatory and governance models with the authorities of federal government agencies.

Many of the legislators allied with the NCAA and Power 5 built their political careers on states’ rights and free markets, yet they have led the charge for protective big government federal legislation.

C. Divide and Conquer

The NCAA and Power 5 have employed divide-and-conquer strategies that pit athletes against one another.

With the able assistance of their world-class lawyers, lobbyists, and spin doctors, the NCAA and Power 5 have portrayed “Olympic” and women’s sports/athletes as victims of any reform that recognizes the true value of Power 5 football and men’s basketball players.

Status quo stakeholders even invented a new theory in 2020 during the early phases of the NIL debate called “displacement,” designed to drive a wedge between profit athletes in Power 5 football/men’s basketball and nonrevenue/female athletes.

The displacement theory assumes zero-sum financial and equity worlds in college sports.

In the zero-sum financial world, every dollar of revenue that might go to profit athletes in Power 5 football and men’s basketball is a dollar stolen from nonrevenue athletes, female athletes, or athletic department budgets.

In the zero-sum equity world, any reform that addresses the equity interests of profit athletes necessarily steals equity from nonrevenue and female athletes.

This way of thinking suggests the richest athletics departments in college sports don’t have enough money to address the financial and equity interests of all athletes.

Thus, there must be winners and losers in a battle for money and equity.

The NCAA’s and Power 5’s zero-sum thinking is a barrier to athlete harmony because it undermines potential athlete organization efforts and distracts decision-makers from the NCAA’s and Power 5’s true motives.

Hearings on college sports in Congress and state legislatures are littered with doomsday predictions that meaningful reform to the status quo regulatory or business model will have devastating consequences for Title IX and gender equity, including eliminating women’s sports.

Proponents of these narratives have yet to produce evidence of actual harm, and lawmakers have not demanded it.

The presumption of harm seems to be adequate to influence lawmakers.

Indeed, little legal expertise on Title IX and gender equity has made its way into the congressional debate. Through twelve hearings over four years and sixty-two available witness slots, legislators appear to be satisfied with NCAA and Power 5 fearmongering on those issues.

Additionally, despite repeated and legitimate concerns over Title IX enforcement, Congress has yet to require testimony from a representative from the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR), which is responsible for Title IX compliance.

OCR’s dismal track record on Title IX compliance and unresponsiveness to female athlete’s concerns has left female athletes with the choice between (1) acquiescing to Title IX violations by their institutions (and indifference from the NCAA and conferences) or (2) filing federal lawsuits that are costly, lengthy, and whose outcomes are uncertain.

Moreover, the NCAA and Power 5’s use of Title IX and gender equity to divide athletes and prevent sensible, equitable reform for all athletes is ironic given the NCAA’s and Power 5’s fifty-year-long neglect of Title IX, gender equity, and the welfare of female athletes.

(see the DYK podcast clip below from our interview with Ithaca College professor Dr. Ellen Staurowsky; the full podcast episode is available through the podcast link at the bottom of the homepage)

The NCAA’s indifference to Title IX was aided by a 1999 Supreme Court decision—NCAA v Smith—in which the Court held that Title IX didn’t apply to the NCAA because it does not receive federal education funding.

On December 20, 2022, House members Alma Adams (D-NC), Suzanne Bonamici (D-OR), and Lori Trahan (D-MA) introduced the Fair Play for Women Act that would hold the NCAA accountable under Title IX and provide athletes a private right of action under the bill.

Senator Chris Murphy (D-CT) introduced a companion bill in the Senate.

On February 7, 2024, companion bills were reintroduced in both chambers.

The bill has not made it out of committee.

To bolster their divisive equity themes, the NCAA and Power 5 also make utilitarian arguments to justify protective legislation. They emphasize the interests of the “many” (nonrevenue and female athletes) over the “few” (profit athletes in Power 5 football and men’s basketball) with no acknowledgment of the vastly different roles the many and few play in the overall business model.

In their January 12th, 2023 “State of the Association” speeches at the NCAA convention, NCAA Board of Governors Chair Linda Livingstone (Baylor University President) and new NCAA President Charlie Baker used utilitarian arguments in an open appeal to stakeholders for protective federal legislation.

Similarly, in response to a California revenue sharing bill introduced in February 2023, new NCAA spokesman Tim Buckley invoked utilitarian arguments to oppose the legislation.

Power 5 schools in California likewise opposed the bill on gender equity grounds.

The divide-and-conquer strategy has uncomfortable racial implications.

Profit athletes in Power 5 football and men’s basketball are disproportionately African American. The talents and labor of these athletes underwrite the $20 billion-a-year college sports industry, including scholarship money and administrative overhead for nonrevenue and female athletes and sports.

In contrast, nonrevenue and female sports athletes are disproportionately white.

This is an inconvenient truth for institutional stakeholders and decision-makers.

D. Lean into Patriotic Themes: “Olympic Sports” and the “Olympic Development Pipeline”

The NCAA, Power 5, and allied lawmakers repeatedly assert that if profit athletes in Power 5 football and men’s basketball keep a fair share of the wealth they create, then Olympic sports will be eliminated.

This, in turn, will decrease our Olympic development pipeline and result in a less competitive Olympic program.

This fearmongering is usually tied to the prospect of meaningful revenue sharing or employee status for athletes.

Framing the issue this way is an acknowledgment that Power 5 football and men’s basketball subsidize our national Olympic development program. (for a discussion of the inequities in this model, see Dr. Victoria Jackson’s July 2021 article in The Athletic, “We’re all complicit to an extent: How Team USA uses college football and basketball as funding sources”)

This model is uniquely American; in almost every other country in the world, governments fund Olympic development.

The NCAA claims primary credit for our Olympic success and propagandizes its role as America’s Olympic development pipeline.

The NCAA also claims credit for developing Paralympians even though it does not officially sponsor Paralympic sports.

Putting aside the question of why college football and men’s basketball athletes, rather than our government, should underwrite Olympic development, the NCAA’s use of Olympic sports has two benefits to the NCAA/Power 5 business model.

One, it justifies and normalizes the massive, regressive diversion of wealth from profit athletes in football and men’s basketball to sports and athletes who cannot pay for themselves.

This justification aligns with former NCAA President Myles Brand’s conceptualization and articulation of the “collegiate model” in 2006 as a financial framework in the business of college sports.

Brand’s model—disingenuously tied to education—mandates the maximization of revenue from football and men’s basketball and then massive redistributions of that revenue to sports and athletes who lose money. (see DYK podcast interview clip from Dr. Richard Southall below; the full episode can be found in our Podcast link on the homepage)

While Brand identified increased participation opportunities for nonrevenue and female athletes as a rationalization for his model, in fact, what Brand was saying is that the athletes who generated this wealth have no legitimate claim to it, and the NCAA, conferences, and schools can do whatever they want with it.

This is a bedrock principle of the big-time college sports juggernaut and extends far beyond Olympic development and captures non-Olympic, nonrevenue sports and athletes and Olympic sport athletes that have no realistic chance of participating in the Olympics.

It is not coincidental that after Myles Brand conceptualized the collegiate model, the NCAA, conferences, and institutions stopped referring to money-losing sports and athletes as “nonrevenue” and began referring to them as “Olympic” sports and athletes.

Two, it allows the NCAA and Power 5 to employ patriotic themes to appeal to decision-makers’ sense of duty to the country.

The NCAA uses broad patriotic themes in much of its public relations messaging and develops relationships with well-respected American public leaders (e.g., former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, former CIA Director Robert Gates, Surgeon General of the Army Dr. Nadja West).

This is a powerful tactic that blunts scrutiny and criticism of the business model.

The NCAA’s portrayal of Olympic sports and the developmental pipeline has several head-spinning ironies.

First, a substantial number of NCAA Olympic sports athletes are not American citizens. For example, college rosters in sports such as tennis, soccer, and golf have many international athletes.

In reality, the NCAA is not only providing an Olympic pipeline for American athletes but also for athletes from other countries.

Should American football and men’s basketball players be required to subsidize Olympic development pipelines for the entire world?

Second, these very athletes whose labors fund the Olympic pipeline(s) cannot participate in the Olympics.

American football is not an Olympic sport, and since 1992, when the US permitted professional basketball players to play on our Olympic team, no college player has been selected to an Olympic basketball roster.

Third, the NCAA’s claims of superior Olympic training at universities and colleges don’t account for the number of athletes who defer or interrupt their college careers to train elsewhere. Simone Biles and other medal-winning female Olympic gymnasts are notable examples.

Finally, the NCAA wraps itself in the American flag through its Olympic sports propaganda in Congress to justify and federalize illegal and unAmerican compensation limits that disproportionately impact African American athletes.

E. Make the Extraordinary Seem Common

The NCAA and Power 5 have brilliantly normalized as reasonable and commonplace breathtaking federal protections and immunities unprecedented in college sports (preemption, antitrust immunity, and non-employee status of athletes).

With respect to their campaign for a bill that would make it impossible for athletes to be employees of their university, NCAA and Power 5 witnesses speak in terms of recognizing the “special status” of athletes (as non-employees). They seek merely to “affirm,” “clarify,” and “codify” that athletes are students, not employees.

In their quest for antitrust immunity, the NCAA and Power 5 simply want a “safe harbor” from endless, spurious litigation that would allow the NCAA to pass “sensible legislation for the benefit of all athletes.”

On federal preemption of state laws that conflict with NCAA compensation limits or eligibility rules, the NCAA and Power 5 seek one “uniform standard” to avoid an unworkable “patchwork” of conflicting state NIL laws.

Yet no one has posed the most critical threshold question relevant to these extraordinary asks: Why would the federal government use Constitutional and statutory powers to protect the business interests of a small group of private education nonprofits like the NCAA and Power 5 conferences?

Why did Congress even grant them an audience for these audacious exemptions from American laws and values?

F. Co-Opt The “Athlete Voice” to Create the Perception of Athlete “Consensus” on NCAA Values and Congressional Goals

As the battle for who gets to decide rages on, a related question is equally important: Will athletes—particularly those in Power 5 football and men’s basketball—have a meaningful seat at decision-making tables?

Despite the NCAA and Power 5’s frequent invocation of the “athlete voice,” the fact remains that they have uniformly prevented athletes from having a meaningful voice.

Athletes are not members of the NCAA.

Few stakeholders are aware of this fundamental flaw in the NCAA regulatory model.

The membership of the NCAA comprises 1,100 colleges and universities that pay annual membership dues. As non-members, athletes have no standing within the NCAA to demand a seat at the table in discussions regarding their interests and welfare.

Athlete interests are presumed to be protected by institutional representatives serving on NCAA boards and committees or holding some NCAA-sanctioned status at the institutional level.

The only athlete-led representation body recognized by the NCAA is the Student Athlete Advisory Committee (SAAC). SAAC is an NCAA-sanctioned body and exists at the pleasure of the NCAA, conferences, and member institutions.

While other athlete advocacy groups have sprung up organically, often in response to flashpoint events (e.g., George Floyd murder, fall football during COVID), they have yet to be granted a seat at NCAA decision-making tables, and few have been granted even an audience with NCAA leaders.

SAAC groups exist at the institutional, conference, and NCAA levels (by Division).

The SAAC group with the most meaningful contact with NCAA decision-makers is the Division I national SAAC, which has thirty members. National SAAC members are “nominated” for national service and have historically been disproportionately white, non-revenue athletes.

Even former NCAA President Mark Emmert concedes weaknesses in the composition of SAAC.

In a September 2022 interview, Emmert said:

“How are you going to make this all work where you've got a strong voice for students? You've got the Student Athlete Advisory Committees. That's great. And I love our SAAC committees, but you need more football representation, you need more basketball representation, you need more minority student representation. It's not as representative as it should be. And getting that done has been a real thorny problem.”

The NCAA and Power 5 have employed SAAC representatives to send letters to select Congressional decision-makers that suggest “consensus” among all athlete stakeholder groups on the need for protective federal legislation that aligns with NCAA and Power 5 business interests.

To be clear, we are not criticizing the athletes who serve on the various SAAC committees. We criticize the NCAA’s use of those structures to control, manipulate, and limit the athlete voice.

Importantly, through the Congressional debate and twelve hearings, only one current or recently graduated Power 5 football or men’s/women’s basketball player testified (see witness list image below).

That lone witness, UCLA quarterback Chase Griffin, testified at the January 18, 2024, hearing in the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Innovation, Data, and Commerce.

The hearing was built around proposed legislation from Subcommittee Chair Gus Bilirakis (R-FL), which would substantially limit athletes’ economic freedoms, provide the NCAA preemption, antitrust immunity, and non-employee status for athletes, and place the regulation of college sports in the hands of a federal commission dominated by NCAA/Power 5 insiders.

Mr. Griffin offered a compelling, thoughtful case in favor of free markets and against intrusive government regulation.

In the video clip below, Mr. Griffin responds to questions from Robin Kelly (D-IL) on the impact of federal legislation proposed by Mr. Bilirakis.

When Charlie Baker accepted the job as NCAA President, he vowed to go on a listening tour to understand how institutional stakeholders viewed the issues facing college sports.

He claims to have spoken to over 1,000 athletes and met with representatives from every conference.

From his listening tour, Baker has concluded that there is an absolute consensus among athletes that they should not be employees of their university.

Baker carried that message to Congress to lobby for a federal bill that would make it impossible for athletes to be employees.

Baker invoked feedback from Division I SAAC and a forum he attended with Senator John Thune (R-SD) at Augustana University, a D-II school in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

Baker testified to Congress that he has not talked to a single athlete who “wants” to be an employee.

Apparently, Mr. Baker has not talked to Dartmouth men’s basketball players who achieved employee status and voted to form a union under the National Labor Relations Act.

Moreover, if Baker sees value in attending forums at Division II schools, why wouldn’t he also see value in forums featuring football and basketball athletes at Michigan, Florida State, Georgia, or Washington?

The NCAA’s capacity to “listen” to college athletes seems to exclude the very athletes whose labors drive the value in the college sports entertainment-industrial complex.

If there was ever a time for athlete representation independent of NCAA control and manipulation, it is now.

On the crucial question of who gets to decide, athletes should be at the top of the list, not the bottom.