V. Business Regulation/Consumer Protection

The Federal Trade Commission Bureau of Consumer Protection (FTC) has jurisdiction over a broad range of business practices. It gets congressional authority from the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTCA).

The FTC’s mandate “is to protect consumers against unfair, deceptive, or fraudulent practices. The Bureau enforces a variety of consumer protection laws enacted by Congress, as well as trade regulations and rules issued by the Commission [FTC].

Its actions include individual company and industry-wide investigations, administrative and federal court litigation, rulemaking proceedings, and consumer and business education. In addition, the Bureau contributes to the Commission’s “on-going efforts to inform Congress and other governmental entities of the impact that proposed actions could have on consumers.” (emphasis added).

While the FTC has a consumer-oriented mission, the NCAA and Power 5 seek to use its powers to protect and promote NCAA/Power 5 regulatory and economic interests.

The NCAA has successfully persuaded Congress to use the FTC’s authority to regulate athlete agents (discussed below).

In their current congressional campaign, the NCAA and Power 5 seek to invoke the FTC’s regulatory authority.

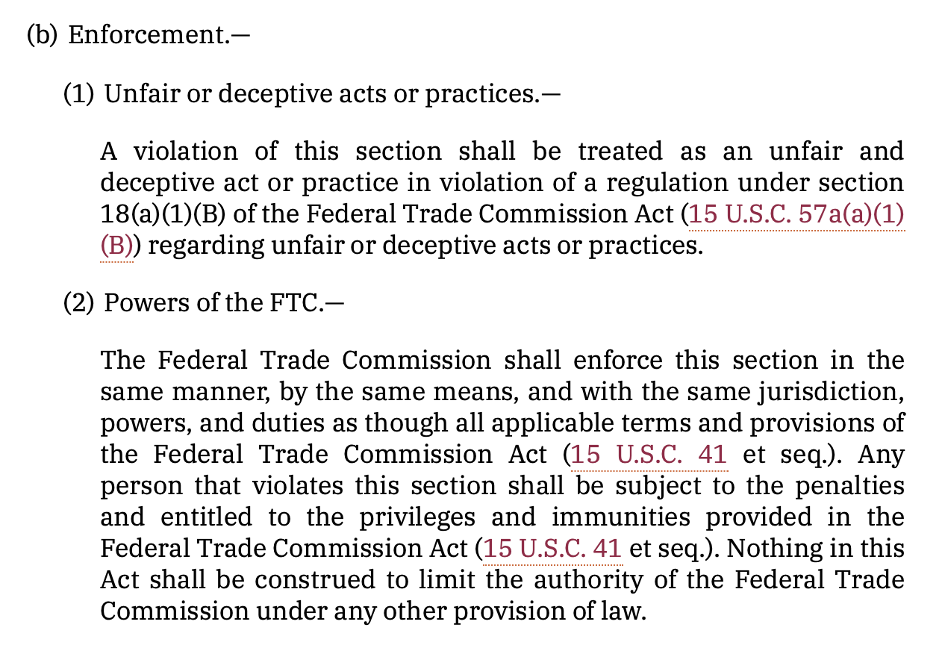

Several NCAA/Power 5-friendly bill proposals would likewise invoke use the FTC’s and FTCA’s existing regulatory authority or create a new FTC office to oversee a federalized college sports model (see, e.g., images below from Roger Wicker’s [R-MS] 2020 “Collegiate Athlete Compensation Rights Act” and Anthony Gonzalez and Emanuel Cleaver’s [R-OH/D-MO] 2020 “Student Athlete Level Playing Field Act”).

By invoking the FTCA authorities, the NCAA and Power 5 stealthily invoke the potent law enforcement and investigatory powers of the Act, including subpoena power.

Subpoena power in a federalized college sports regulatory structure would permit the NCAA—through surrogate government action—to force witnesses to provide documents and testimony.

The most likely subpoena targets will be “bad actors” in the eyes of the NCAA and Power 5, including (1) athletes, their family members, and associates, (2) athlete agents, (3) boosters, and (4) NIL collectives.

NCAA President Charlie Baker has emphasized a “consumer protection” approach in the NIL market, arguing that there should be a standardized contract for NIL deals and mandatory reporting requirements.

Baker’s consumer protection arguments are built around NCAA/Power 5 “bad actor” narratives.

Baker has not explained, nor has he been asked to explain, why the NCAA can’t accomplish that goal through voluntary rulemaking without federal legislation.

No FTC representative has testified in any of the eleven congressional hearings held since 2020.

Given the NCAA and Power 5’s reliance on the FTC as a federal regulator and the FTC’s stated mission to “inform Congress and other governmental entities of the impact that proposed actions may have on consumers,” the FTC’s exclusion from the hearings highlights the power of the NCAA/Power 5 lobbying campaign and the inadequacy of congressional “debate” on college sports regulation.

A. The SPARTA Precedent

To understand how the NCAA and Power 5 view the role of the FTC, it's instructive to rewind to 2004 and the passage of the Sports Agent Responsibility and Trust Act (SPARTA).

SPARTA followed a wave of state athlete-agent laws in the 1980s and 1990s designed to tightly regulate agents and discourage them from forming relationships with college athletes. State agent laws explicitly relied on NCAA amateurism-based values to justify regulation.

Note: For a detailed discussion of the purpose and evolution of athlete-agent laws, see the State Legislatures Tab in the Explore menu on the Homepage.

As more states passed legislation to regulate athlete agents, some stakeholders believed there should be uniform state laws. In the late 1990s, the Uniform Law Commission (ULC) considered a uniform athlete agent law that states could adopt. In 2000, the ULC approved the Uniform Athlete Agent Act (UAAA).

The UAAA provided for (1) uniform registration and certification of agents, including disclosure and reporting requirements, (2) uniform agency contract terms for NCAA-permissible agent relationships, (3) certain prohibited conduct such as providing false information, promises, or representations to induce an athlete to enter into an agency contract, initiating contact with an athlete without being registered in the state, providing anything of value to a “student-athlete” as an inducement to enter into an agency contract, (4) a “cooling off” or mandatory waiting period before any agency contract becomes effective, (5) education requirements for agents, and (6) civil and criminal penalties and (7) rights of action for institutions and athletes against agents who violate the Act (rights of action for athletes were not available under the UAAA until in 2015).

The UAAA was tightly aligned with NCAA amateurism values and athlete agent rules. The NCAA fully supported the UAAA and encouraged NCAA members to lobby their state legislatures to adopt it.

As state athlete-agent laws evolved into the 21st century, some stakeholders—notably the NCAA—believed a federal law was preferable to state-based regulation.

In 2004, Congress passed SPARTA, an athlete agent law that deferred to NCAA amateurism-based values. (for a discussion of SPARTA’s legislative history, see Edmonds, Manz, and Kettleman “Congress & Sports Agents: A Legislative History of the Sports Agent Responsibility and Trust Act” [2008])

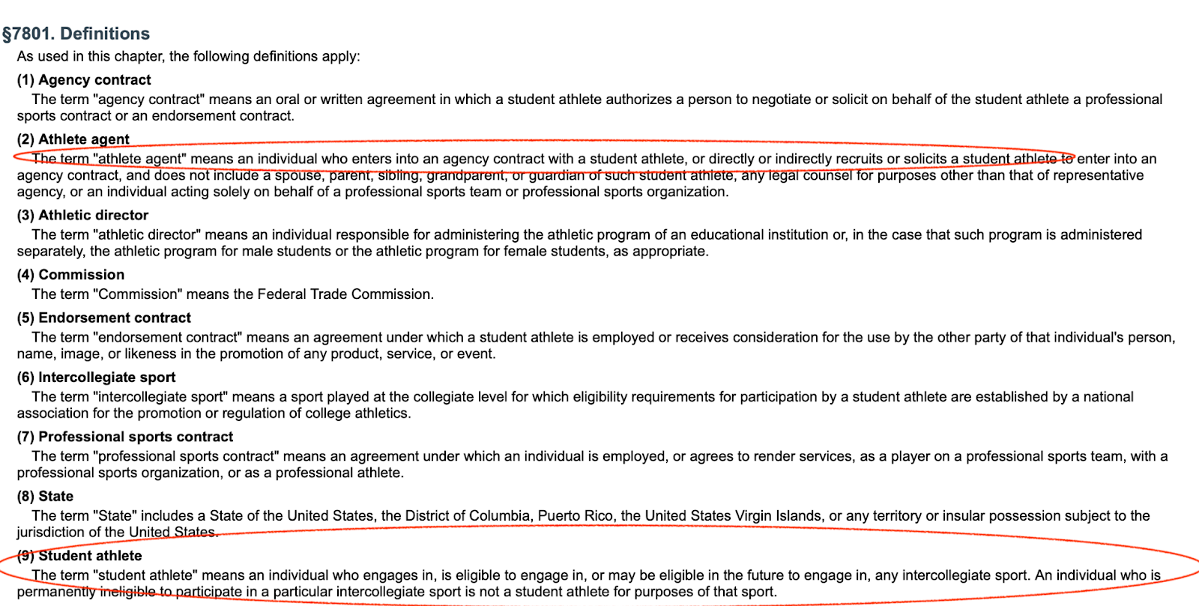

SPARTA is modeled after the UAAA and directed to college sports and agents rather than professional ones. The Act defines “Athlete Agent” as “an individual who enters into an agency contract with a student-athlete, or directly or indirectly recruits or solicits a student-athlete to enter into an agency contract…” (emphasis added)

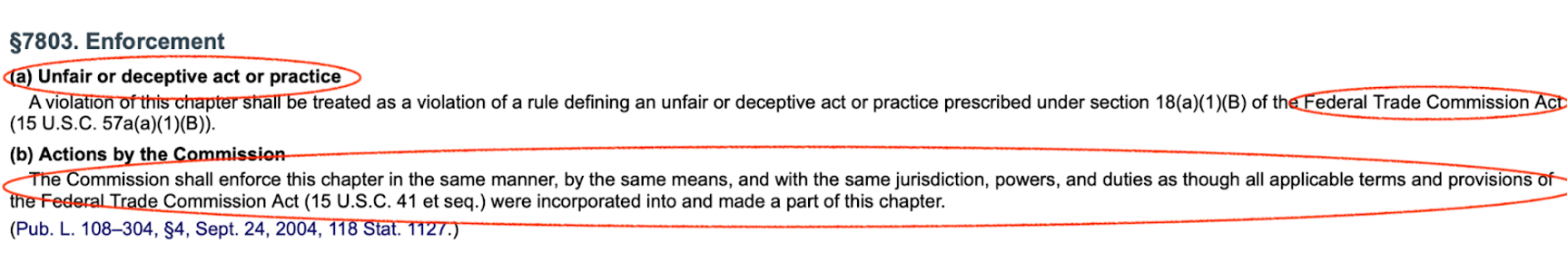

SPARTA uses a dual federal-state regulatory model that does not preempt state laws. At the federal level, a violation of the Act is treated as an unfair and deceptive trade act under the FTCA.

The enforcement section of SPARTA states that the FTC “…shall enforce this chapter in the same manner, by the same means, and with the same jurisdiction, powers, and duties as though all applicable terms and provisions of the [FTCA] were incorporated into and made part of this chapter.”

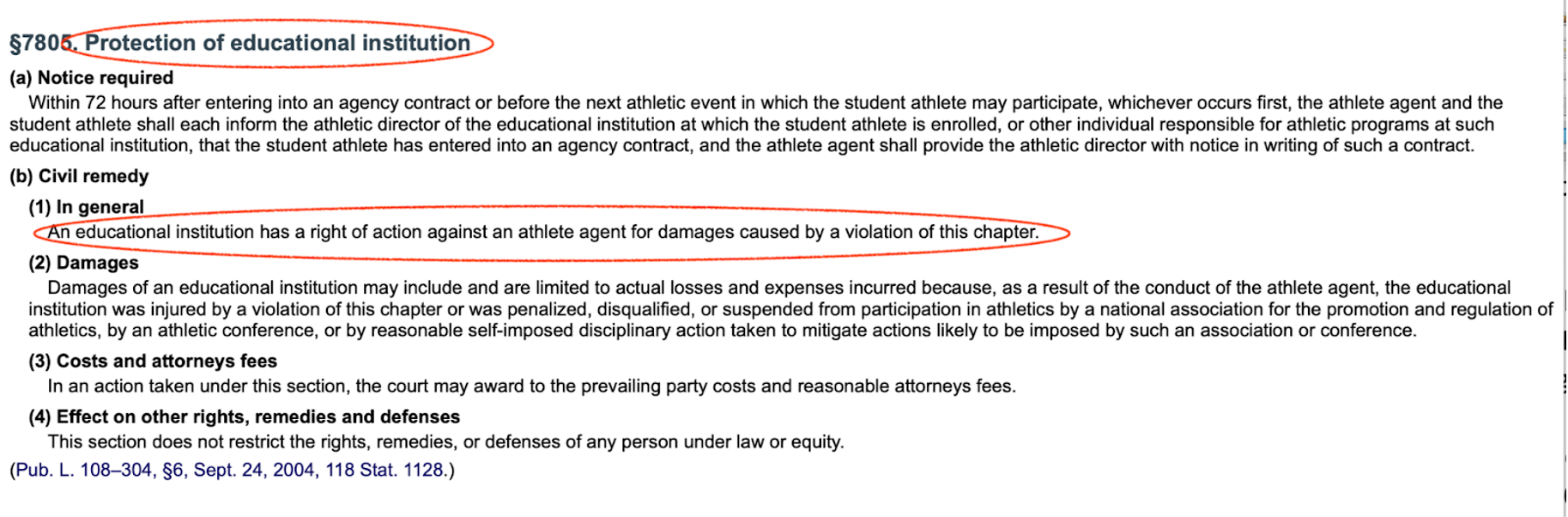

SPARTA permits rights of actions by states and educational institutions (“Protection of Educational Institution”) against agents for violating the Act. Importantly, as discussed in more detail below, SPARTA does not provide a right of action for athletes who have been harmed by the actions of an agent.

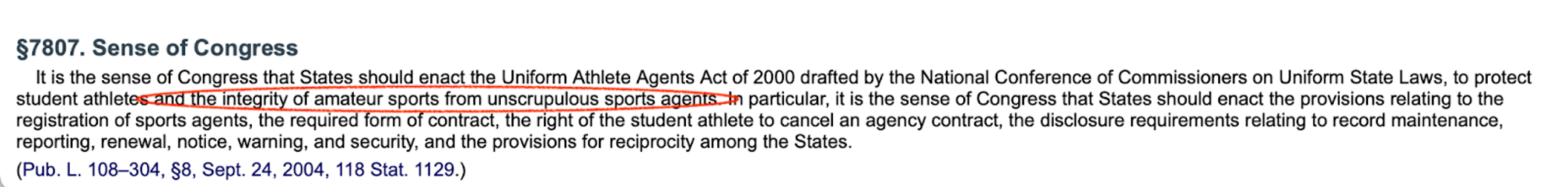

Congress’ deference to NCAA amateurism-based values is highlighted in SPARTA’s “Sense of Congress” provision:

“It is the sense of Congress that States should enact the Uniform Athlete Agents Act of 2000 drafted by the [ULC] to protect student-athletes and the integrity of amateur sports from unscrupulous sports agents. In particular, it is the sense of Congress that States should enact the provisions relating to the registration of sports agents, the required form of contract, the right of the student-athlete to cancel the agency contract, the disclosure requirements relating to record maintenance, reporting, renewal, notice, warning, and security, and the provisions for reciprocity among the States.” (emphasis added)

Proponents of SPARTA justified it as a necessary safeguard to protect vulnerable college athletes from predatory agents. Yet, as noted above, the bill did not provide any way for athletes to protect their interests.

Congressman Mel Watt (D-NC) tried to amend initial drafts of SPARTA to include a right of action for athletes.

The best he could do was to include a “Limitation” provision that said, “[n]othing in this chapter shall be construed to prohibit an individual from seeking any remedies available under existing Federal or State law or equity.”

In a fitting irony, the “Limitation” provision immediately follows the “Protection of Educational Institution” section that explicitly grants an educational institution a right of action against an agent for any damages caused by a violation of SPARTA.

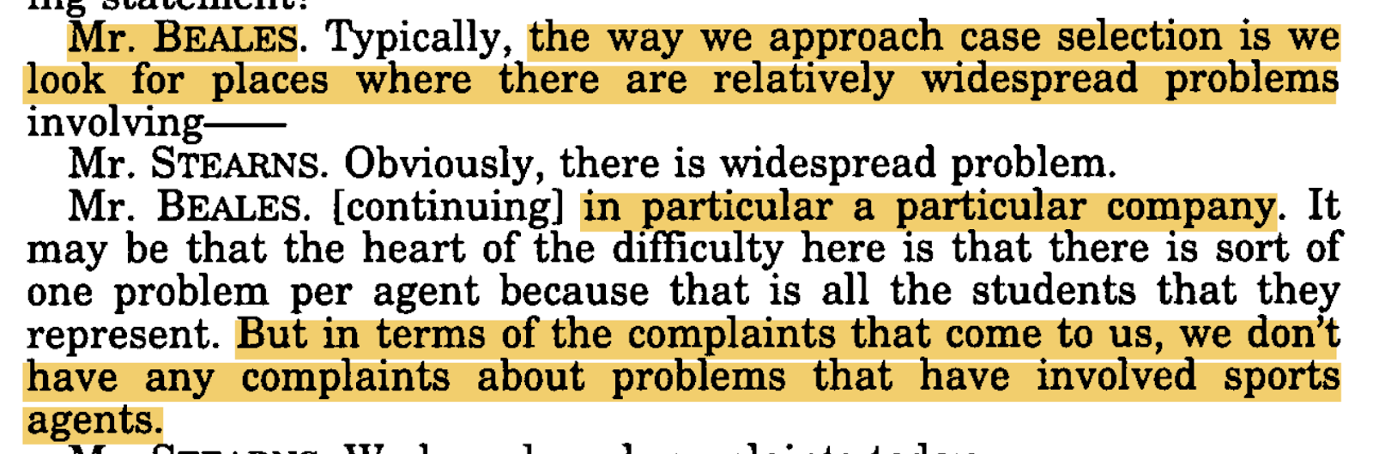

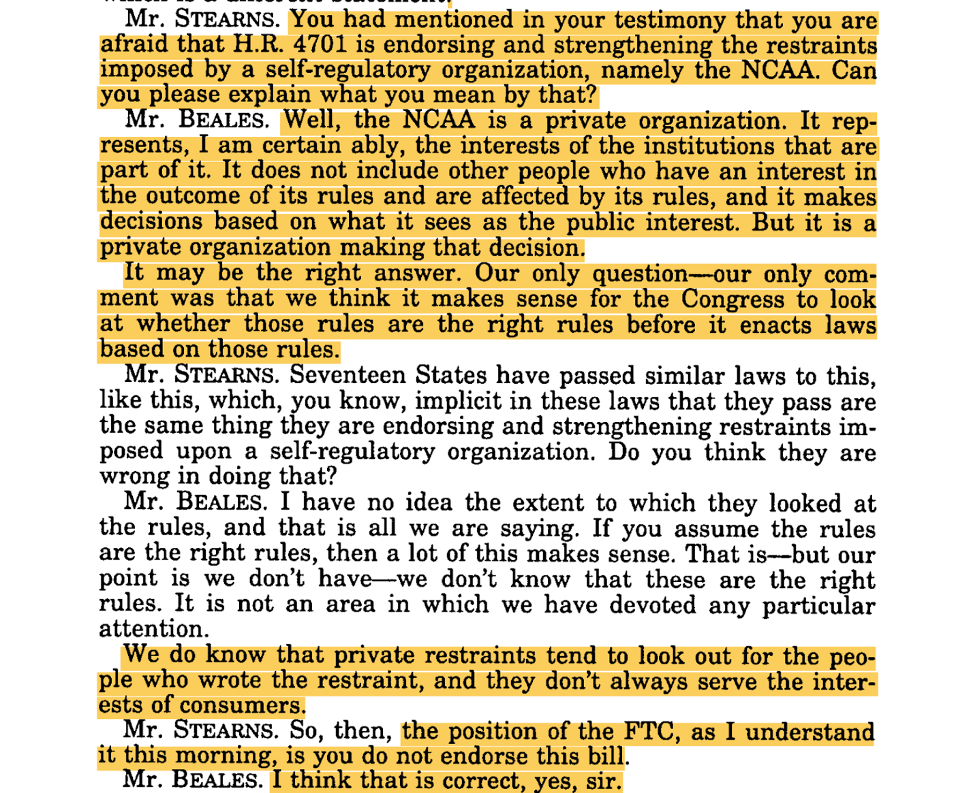

Howard Beales, then the Director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, testified in Congress when SPARTA was being considered in 2002. Beales offered a broad-ranging critique of SPARTA’s premises and its use as a consumer protection tool.

Beales raised several critical points to question SPARTA’s purpose and effectiveness:

(1) Beales suggested that using the FTC to regulate athlete-agent issues wasn’t on a scale that would justify FTC involvement from a policy standpoint.

(2) The FTCA already covers deceptive trade practices, which renders SPARTA redundant and unnecessary.

(3) The adoption of NCAA rules and values as federal standards may function to protect the college sports industry rather than consumers. Beales said Congress should “examine the need for, and appropriateness and carefully examine the underlying private restraint [NCAA rules] before enacting [them] into law.”

(4) If Congress’s primary concern is protecting athletes, it should enact a law outside FTC jurisdiction giving athletes a private right of action. Beales emphasized this approach would be far more efficient in safeguarding athlete interests than using the FTC as a national athlete agent police force.

(See Edmonds, Manz, and Kettleman)

Beales’ warnings should serve as a cautionary tale in current discussions of the federal government’s role in regulating college sports.

His criticisms of SPARTA are relevant and crucial because they raise the ultimate premise issue: whether it would ever be appropriate for the federal government to adopt and protect private industry business interests and rules as federal law and use its law enforcement powers to promote and protect those interests.

As mentioned above, many of the bills proposed by NCAA/P5-friendly Congressmembers invoke the FTC’s regulatory authority and enforcement capabilities. Some bills cut and paste from SPARTA’s use of the FTC. Similarly, some NCAA/Power 5 proposals would amend SPARTA to expand the “bad actors” list to include boosters, NIL companies, and NIL collectives.

However, there hasn’t been any discussion in Congress or among in-system stakeholders about the appropriateness of federalizing the college sports regulatory and business models to protect a very small collection of private, nonprofit interests.

No FTC member has been called to testify at the eleven congressional hearings on “NIL compensation.” Given the extraordinary power the FTC would theoretically wield under some NCAA-friendly bill proposals, shouldn’t the FTC weigh in today as Mr. Beales did in 2002 regarding SPARTA?

Finally, since SPARTA was passed, the FTC has not pursued a single athlete agent case under SPARTA.