VI. A Modest Proposal

I. Introduction

The NCAA, Power 5, and member institutions have proven incapable of intelligent, competent self-regulation.

That is precisely why they have been kneeling before Congress since 2020 for a federal bailout.

These same in-system leaders have proven unwilling to share information and documents with athletes or the public that might illuminate the truth of the big-time college sports business model and inform the debate on college sports reform.

They prefer to conduct their business in star chamber settings where they have complete control over the process and the people who have input into it.

Yet they continue to contend their primary objective is to further athlete interests.

Athletes and external decision-makers should be asking whether institutional stakeholders have forfeited the right to call the shots.

In that regard, we offer some suggestions for what athletes can do right now to claim their power and control their destiny.

These suggestions focus mainly on transparency, accountability, and access to the same information and documents the NCAA and Power 5 have used to manipulate Congress and public opinion.

They shouldn’t be controversial, but the NCAA, Power 5, and their loyal supporters will likely view them that way.

Underlying these suggestions is the assumption that athletes (1) will be committed and motivated to acquire the knowledge necessary to effectively structure their goals, whatever they may be, and (2) organize on their own to advocate for intelligent athlete-centered reform.

The purpose of the DYK project is to provide education and advocacy tools for athletes (and other stakeholders) to do just that.

In Congress, federal courts, administrative agencies, and state legislatures, the NCAA, Power 5, and their allies have pursued their interests with intense motivation.

They are not going away, and their motivation won’t waver.

If athletes don’t match and exceed institutional interests' motivations, they could lose the battle for athletes’ rights and the future of college sports.

In the short run, athletes don’t need a formal association to lead their cause.

Similarly, athletes don’t need to petition the National Labor Relations Board for employee status and formal collective bargaining to get their issues on the table now.

Athletes have it within their power to organize quickly and organically through the magic of technology and social media.

The last thing the NCAA and Power 5 want to see is an alliance of well-informed, motivated athletes demanding transparency and a seat at decision-making tables before the NCAA and Power 5 impose their will and permanently limit athletes’ basic rights as Americans.

A. The Current NCAA and Power 5 Chessboard

In analyzing the NCAA/Power 5 chessboard, it’s crucial to understand that their ultimate objective is absolute control over the regulatory and business models of college sports.

That goal has never changed, nor will it.

They don’t want anyone, including Congress, state legislatures, federal agencies, or the US Supreme Court, telling them what to do or how to do it.

The NCAA and Power 5’s collective arrogance brought them to where they are today, yet they are still blinded by it.

However, a whirlwind of events over the last year has materially altered the NCAA and Power 5’s pathway to regulatory supremacy.

In response to these events, the NCAA and now the Power 2—the Big Ten and SEC—have gone underground to reassess and manage their chessboards.

The number of power players and decision-makers has shrunk to a very small number, operating in secretive environments with no accountability to athletes or other stakeholders.

Activity in conference realignment, Congress, federal litigation, administrative agencies, and state legislatures point toward momentum for the NCAA and Power 2’s next move.

It is critical that athletes view the current legal and regulatory chessboard the way NCAA lawyers, lobbyists, and spin doctors do. They are calling the shots right now more so than college presidents, conference commissioners, and NCAA bureaucrats.

A timeline of events over the last year provides clues to how key stakeholders and decision-makers see their options and how athletes may choose to respond.

B. Timeline of Events of the Last Year (March 2023 - March 2024)

2023 (March 29th) – the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Innovation, Data, and Commerce Subcommittee chaired by Rep. Gus Bilirakis (R-FL) holds a hearing titled “Taking the Buzzer Beater to the Bank: Protecting College Athletes’ Dealmaking Rights”; hearing’s timing capitalizes on March Madness themes; six witnesses testify; five are pro-Power 5/NCAA, only one athlete advocate; the hearing leans into equity-based themes and the negative impact revenue sharing or employee status would have on Olympic and women’s sports

2023 (April 4th) - Hubbard v NCAA federal class-action antitrust lawsuit filed against NCAA and Power 5 for “back” Alston education benefits; athletes seek damages and injunctive relief; suit filed in Northern District of California before Judge Claudia Wilken, who heard O’Bannon and Alston suits; athletes jointly represented by Steve Berman and Jeffrey Kessler who teamed up in Alston and House

2023 (May 24th) - Representative Gus Bilirakis (R-FL) circulates a “Discussion Draft” of a bill titled “Fairness, Accountability, and Integrity in Representation of College Sports Act,” FAIR would regulate the NIL marketplace through a federal, nonprofit corporation; the Department of Commerce’s Office of the Inspector General would have oversight authority over the federal corporation; bill includes preemption provision that goes far beyond state NIL laws

2023 (May 24th) - Representatives Mike Carey (R-OH) and Greg Landsman (D-OH) introduce a bill titled the “Student Athlete Level Playing Field Act”; the bill federalizes the NIL market

2023 (June 8th, 9th) - Power 5 and NCAA leaders descend on Congress; key leaders meet with Congress members to lobby for protective federal legislation; the University of Arizona hosts “panel discussions” in D.C. on June 8th designed to complement lobbying campaign; panels are comprised mostly of Power 5/NCAA insiders including SEC commissioner Greg Sankey, ACC commissioner Jim Phillips, NCAA President Charlie Baker, Power 5 presidents and chancellors, Power 5 athletics directors, and a Power 5 head football coach

2023 (June 12th) - NCAA announces its first-ever “College Athlete Day”; in partnership with the White House; 52 national championship teams from all three Divisions make a trip to the White House to celebrate college sports; all teams are from nonrevenue-producing sports; Vice President Kamala Harris presides; NCAA President Charlie Baker attends; NCAA also honors former Presidents who were college athletes

2023 (June 16th) - Senators Tommy Tuberville (R-AL) and Joe Manchin (D-WV) issue draft bill titled “Protecting Athletes, Schools, and Sports Act of 2023”; NCAA has first-line responsibility for regulatory oversight, investigations, reporting to Congress, and imposition of penalties; bill substantially curtails the transfer market

2023 (July 20th) – Sens. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), Cory Booker (D-NJ), and Jerry Moran (R-KS) release discussion draft bill “College Athletes Protection and Compensation Act of 2023”; bill is hailed as bipartisan compromise but moves substantially toward NCAA/Power 5 goals; bill contains preemption and provision that its terms cannot create federal or state liability for institutions prior to bill’s enactment; does not address athlete employee status

2023 (July 21st) – Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) releases discussion draft bill that is naked power grab; proposal includes sweeping preemption, antitrust immunity, and non-employee status provision; bill is similar in structure to Sen. Marco Rubio’s bill released June 18th, 2020; NCAA would be the sole regulator in college sports; preemption provision in Cruz bill would nullify the Texas anti-NCAA enforcement NIL bill signed by Texas Governor Greg Abbott (R) just six weeks earlier

2023 (July 25th) – Sens. Tommy Tuberville (R-AL) and Joe Manchin (D-WV) release official version of “Protecting, Athletes, Schools, and Sports Act of 2023”; bill substantially curtails transfer market and includes broad preemption that would nullify/prevent all state laws that relate in any way to athlete compensation/eligibility including revenue sharing laws; bill turns the clock back on athletes’ rights to pre-Alston/transfer/NIL status quo; bill wholesale incorporates NCAA infractions/enforcement apparatus as rulemaking and enforcement authority; NCAA President Charlie Baker applauds the bill

2023 (July 26th) - Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) and Rep. Lori Trahan (D-MA) rerelease “College Athlete Economic Freedom Act”; bill focuses on NIL; facilitates “collective representation” (players’ associations) for athletes but does not confer employee status; requires disclosure of group licensing deals and permission from athletes, but does not explicitly require group license holders to compensate athletes; provides NIL rights and visa status protections for international athletes; includes preemption of state laws (limited to NIL)

2023 (July 27th) - the University of Colorado Board of Regents votes unanimously to approve Colorado’s departure from the Pac-12 Conference to join the Big 12 as of the summer of 2024

2023 (August 4th) - the universities of Oregon and Washington announce they are leaving the Pac-12 to join the Big Ten; the universities of Arizona, Arizona State, and Utah announce they are leaving the Pac-12 for the Big 12; decisions mark the death knell for the Pac-12

2023 (September 13th) - Dartmouth College men’s basketball players file a petition with the National Labor Relations Board seeking to form a union; as with the Northwestern University football team’s unionization attempt in 2014, Dartmouth athletes must first establish they are employees

2023 (September 18th, 19th) – Power 5 leaders return to Washington to persuade congress members to pass protective federal legislation

2023 (September 20th) – House Small Business Committee holds hearing titled “Athletes and Innovators: Analyzing NIL’s Impact on Entrepreneurial Collegiate Athletes”; Committee Chair is Roger Williams (R-TX); Committee members and NCAA/Power 5 witnesses emphasize “predatory agents and bad actors,” the “patchwork” of conflicting state NIL laws, the “Wild West” of NIL activity, “national standard,” “uniformity,”; several Committee members suggest hearing demonstrates a “bipartisan” approach to legislation

2023 (October 23rd) - Georgia Senator Raphael Warnock hosts SEC Commissioner Greg Sankey and Big Ten Commissioner Tony Petitti to discuss how “Congress can best support student athletes”

2023 (October 17th) - Senate Judiciary Committee holds a hearing titled “Name, Image, and Likeness and the Future of College Sports”; Judiciary has jurisdiction over antitrust issues and would bless any antitrust immunity for the NCAA and Power 5; hearing marks congressional debut of NCAA President Charlie Baker; seven witness testify with six advocating NCAA/Power 5 goals and one advocating for athlete interests; NCAA/Power 5 witnesses urge no-employee status for athletes; imbalanced panel suggests “consensus” on the issue

2023 (November 3rd) - in the House v NCAA NIL case, Judge Wilken issues an order granting the athletes’ motion to certify the damages class; this is a crucial ruling that permits the case to go forward on damages; order provides a framework for “Broadcast NIL” (through a group licensing approach), “video NIL,” and “third-party” NIL compensation to several “subclasses” of athletes: (1) Power 5 football and men’s basketball scholarship athletes (2) Power 5 women’s basketball athletes, and (3) “Additional Sports Class” (Division I nonrevenue athletes); payments would be made by conferences, not individual schools which minimize Title IX implications because the Power 5 do not receive federal education funds and likely would not be responsible under Title IX; total damage estimates exceed $1.5 billion; under federal antitrust laws, an award of damages is automatically tripled; ruling puts enormous pressure on NCAA and Power 5 to settle

2023 (November 20th) - former University of Colorado football player Alex Fontenot files a federal class action antitrust suit against the NCAA and Power 5 in Colorado, challenging all NCAA compensation limits; the suit is identical to the original purpose of the Alston suit; athletes seek damages and injunctive relief; another set of athletes represented by Steve Berman and Jeffrey Kessler file an identical case in the Northern District of California on December 7, 2023 (see entry below re Carter v NCAA)

2023 (December 1st) - Female athletes at the University of Oregon file a class-action Title IX lawsuit—Schroeder v NCAA—against the University, claiming multiple violations of Title IX; the suit targets Oregon’s NIL collective, its connection to the University, and unequal NIL payments; athletes co-represented by law firm Bailey & Glasser, the same law firm that represents the NCAA in a transfer-related antitrust suit filed on December 7th, 2023 by seven states (see December 7th, 2023 entry)

2023 (December 3rd) - “Power 4” conference commissioners Greg Sankey (SEC), Tony Petitti (Big Ten), Brett Yormark (Big 12), and Jim Phillips (ACC) go to Washington to lobby congressional leaders for protective federal legislation; commissioners meet with Senator Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and House member Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY) among others

2023 (December 5th) - NCAA President Charlie Baker releases a letter to Division I committee members suggesting the creation of a new Division for top-tier, “highest resource” schools; these schools could invest at least $30,000 per year (for at least half of the school’s eligible athletes) into an “enhanced educational trust fund” for equal distribution to athletes consistent with Title IX; the letter also suggests that schools may be able to pay athletes directly for their NIL through group licensing deals (similar in theory to the remedy athletes seek in the House lawsuit); the letter is viewed as a ground-breaking shift in NCAA philosophy and policy on amateurism-based compensation limits; notably, Baker’s letter says the new benefits “provides an operating model the NCAA and its member institutions can incorporate into ongoing discussions with Congress about the future of college sports”

2023 (December 5th/6th) - the Sports Business Journal holds its annual college sports forum in Las Vegas; speakers include NCAA President Charlie Baker, NCAA Board of Governors Chair and Baylor University president Linda Livingstone, NCAA D-I Board Chair and University of Georgia President Jere Morehead, SEC Commissioner Greg Sankey, Big 12 Commissioner Brett Yormark, and ACC Commissioner Jim Phillips; Morehead says Baker's December 5th letter is merely designed to “start a conversation” to consider a path forward; Morehead also says Congress has to be part of the discussion and, importantly, that the SEC and Big Ten conference commissioners have to be “on the same page”; Morehead’s comment on SEC-Big Ten cooperation foreshadows the February 2, 2024 announcement of the Big Ten-SEC “Advisory Group” (see entry for February 2, 2024)

2023 (December 6th) – Senators Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Chris Murphy (D-CT) reintroduce the “College Athletes Right to Organize Act”; the bill would make scholarship athletes employees with rights under the National Labor Relations Act and entitle them to collective bargaining

2023 (December 7th) - SEC commissioner Greg Sankey suggests he was unaware of the “specifics of the [Baker] proposal before its release,” creating the impression that Baker was acting independently of the NCAA Board of Governors and the Division-I Board of Directors

2023 (December 7th) - states of Ohio, Colorado, Illinois, New York, North Carolina, Tennessee, and West Virginia file federal class-action antitrust lawsuit in West Virginia against the NCAA seeking to strike down the NCAA’s transfer restrictions (one-time per rules revised in April 2021) and the NCAA’s “Restitution Rule” (that effectively prevents athletes from seeking temporary legal relief from courts regarding NCAA eligibility decisions); States and NCAA reach a stipulation on athlete eligibility; NCAA agrees not to declare athletes ineligible who were denied a second transfer via NCAA waiver; NCAA’s co-counsel is Baily and Glasser, the same firm that represents female athletes in Schroeder case (see entry for December 1st, 2023)

2023 (December 7th) - Carter v NCAA federal class-action antitrust lawsuit filed against NCAA and Power 5 challenging all NCAA amateurism-based compensation limits; suit is similar in purpose to Jenkins v NCAA (2014 - 2021; consolidated into Alston); athletes seek damages and injunctive relief; suit filed in Northern District of California and assigned to Chief Judge Richard Seeborg rather than Claudia Wilken; athletes jointly represented by Steve Berman and Jeffrey Kessler who teamed up in Alston, House, and Hubbard; complaint identifies Charlie Baker’s December 5th letter as evidence that the NCAA has abandoned its commitment to amateurism-based compensation limits; suit preemptively addresses NCAA claim that compensating profit athletes will divert funds from women’s and other “Olympic” sports

2023 (December 8th) - in a podcast interview with Tulane law professor Gabe Feldman, published the day after Carter was filed, Jeffrey Kessler, while noting that Congress is unlikely to act on college sports legislation in this Congress and that Charlie Baker’s proposal is “moving in the right direction” but not yet sufficient to form the basis for settlement, addressed the impact a global settlement of House, Hubbard, and Carter may have on the NCAA and Power 5’s overall congressional campaign going forward:

Kessler: I think the one thing that might help [the NCAA] with Congress in the future is reaching an antitrust settlement with us…because if the antitrust claims are resolved and approved by the court as fair and reasonable to the classes, both the past damages and the going forward, then it's much easier for Congress to think about the rest of it, right?

Feldman: That's why, to me, the Baker proposal, if you consider a multi-step process to get a settlement, which is difficult with all the different lawsuits out there and the employment cases, but if it's, we will provide a better system going forward, that's more fair—and you may disagree with say we need more detail before we'd ever agree to that—but also is damages for the last six years or whatever the number is, and then if you package that together as a global settlement to bring to Congress to say, we now as the plaintiffs are on board with this, then you start to see a path to say, we're not going to be in this sort of limbo where we're going to get sued constantly.

Kessler: I think if they settled with us, that would be a great step…for the athletes and everyone else going forward in all different ways.

2023 - December 21st - Atlantic Coast Conference files preemptive lawsuit in North Carolina state court against the Board of Trustees of Florida State University seeking a declaration affirming the enforceability of the ACC’s grant of rights provision that severely penalizes schools who leave the ACC for another conference; ACC also makes breach of contract claims

2023 (December 22nd) - Florida State University Board of Trustees files lawsuit in Florida state court against the ACC seeking a declaration that the ACC’s grant of rights provision is unenforceable; FSU makes breach of contract and state antitrust claims

2024 (January 8th) - Florida House member Gus Bilirakis (R-FL) rereleases a discussion draft of the “Fairness, Accountability, and Integrity in Representation of College Sports Act” (FAIR Act); bill contains broad preemption, antitrust immunity, and no employee provisions that would end the athletes’ rights movement; federal powers would reside in a private nonprofit entity governed by a board comprised largely of NCAA, Power 5 and other institutional stakeholders; NCAA President would be a permanent nonvoting member of the board

2023 (January 11th) - Bilirakis issues a press release in which Subcommittee member Debbie Dingell (D-MI) and Senator Ben Ray Lujan (D-NM) show support for the bill; Bilirakis pitches bill as bipartisan; in the third quarter of 2023, Brownstein Hyatt’s (NCAA lobbying firm) lobbying disclosures show that it added lobbyist Gregory Sunstrum to its NCAA lobbying team; Sunstrom served as Dingell’s former chief of staff, deputy chief of staff, and legislative aid

2024 (January 18th) - the United States, the District of Columbia, and the states of Minnesota, Mississippi, and Virginia intervene in the Ohio et al. v NCAA federal antitrust suit in West Virginia challenging the NCAA’s transfer rules; intervention by the United States is significant and places additional pressure on NCAA

2024 (January 18th) - in House v NCAA, the Ninth Circuit denies the NCAA’s Petition for an interlocutory appeal of Judge Wilken’s Order certifying the damages class; the case will go forward on damages; the ruling places pressure on NCAA and Power 5 to decide whether to attempt to settle the case, in whole or part

2024 (January 18th) - House Subcommittee on Data, Innovation, and Commerce, chaired by Rep. Gus Bilirakis (R-FL), holds a hearing titled “NIL Playbook: Proposal to Protect Student Athletes’ Dealmaking Rights”; six witnesses testify; four are pro-Power 5/NCAA; NCAA/Power 5 witnesses and committee members flood the hearing with dire predictions of harm if athletes are deemed employees of their university; critics of an employment model invoke Title IX, Olympic development, and nonrevenue sport interests; for the first time in four years through twelve hearings and sixty-two witness slots, a current Power 5 football athlete—Chase Griffin of UCLA—testifies; Griffin offers a persuasive, comprehensive free market-based rebuttal to the limitations in Bilirakis’s bill and the broader question of the necessity for government regulation in college sports

2024 (January 29th) - the parties in Fontenot and Carter begin a series of opposing procedural maneuvers to consolidate the two cases in either Colorado (Fontenot) or California (Carter); in the NCAA/Power 5 briefing on their motion to transfer Fontenot to California, they abandon their fifteen year-long criticism of the Northern District of California and District Court Judge Claudia Wilken as biased against the NCAA and now contend the N.D. CA is the preferable forum; consolidation of the cases in California would facilitate a global settlement of House, Hubbard, Carter, and Fontenot

2024 (January 31st) - the states of Tennessee and Virginia file a federal antitrust suit against the NCAA challenging the NCAA’s NIL rules, the Interim Policy, and subsequent guidance memos; the suit arises from an unconfirmed NCAA infractions and enforcement probe against the University of Tennessee involving its NIL collective Sprye Sports; at issue is whether a NIL collective associated with a school can engage in discussions with high school or transfer portal athletes about potential NIL deals (before executing them); the suit seeks (1) an order declaring the NCAA’s NIL-recruitment ban violates section 1 of the Sherman Act and (2) a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunctive relief “barring the NCAA from enforcing its NIL-recruiting ban or taking any other action to prevent prospective college athletes and transfer candidates from engaging in meaningful NIL discussions prior to enrollment, including under the NCAA’s Rule of Restitution”

2024 (February 2nd) - SEC and Big Ten announce a partnership to collaborate on big-picture issues in college sports, including pending litigation (particularly House) and the possibility of settling cases, governance proposals, and state laws; partnership comes to be known as the “SEC-Big Ten Advisory Group”; Big 12 and ACC not consulted before Advisory Group was created; move generates speculation that the SEC and Big Ten are planning a departure from the NCAA; SEC commissioner Greg Sankey and Big Ten commissioner Tony Petitti say that is not their intention; in response to why stakeholders outside the SEC and Big Ten are excluded, Sankey says, “Big problems are not solved in big rooms filled with people. You have to narrow the focus a bit. There may be raised eyebrows. We certainly called in advance to communicate what was going to be announced rather than do it in the shadows and have someone report on it. You might as well put things out there.”

2024 (February 5th) - in the Dartmouth NLRB unionization case, the NLRB Regional Director rules in favor of the men’s basketball players and issues her Decision and Direction of Election; applying the common law test for employee status, the Regional Director finds the athletes are employees within the meaning of the NLRA.

2024 (February 7th) - House members Alma Adams (D-NC), Suzanne Bonamici (D-OR), and Lori Trahan (D-MA) re-introduce the Fair Play for Women Act that would hold the NCAA accountable under Title IX and provide athletes a private right of action; Senators Chris Murphy (D-CT) and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) introduce a companion bill in the Senate

2024 (February 23rd) - in the Tennessee NIL suit, U.S. District Court Judge Clifton Corker (E.D. TN) issues a preliminary injunction against the NCAA; under the order, the NCAA is “ restrained and enjoined from enforcing the NCAA Interim NIL Policy, the NCAA Bylaws, or any other authority to the extent such authority prohibits student-athletes from negotiating compensation for NIL with any third-party entity, including but not limited to boosters or a collective of boosters, until a full and final decision on the merits in the instant action.”; the order also prevents the NCAA from enforcing its “Restitution Rule” (NCAA Bylaw 12.11.4.2) that allows it to punish athletes and schools if they seek judicial relief and the case is ultimately resolved in the NCAA’s favor; the ruling permits collectives associated with a particular school to discuss potential NIL deals with high school and transfer portal prospects

2024 (March 1st) - in response to Judge Corker’s order granting Tennessee and Virginia’s motion for a preliminary injunction, Charlie Baker sends a letter to the membership informing them that the Division I Board of Directors directed enforcement staff “to pause and not begin investigations involving third-party participation in NIL-related activities.”

2024 (March 5th) - Dartmouth men’s basketball team votes 13 - 2 to form a union; Dartmouth immediately appeals to the NLRB’s top board; NCAA issues statement restating NCAA opposition to employee status for athletes and the need for federal legislation:

“The NCAA is making changes to deliver more benefits to student-athletes, including guaranteed health care and guaranteed scholarships, but the NCAA and student-athlete leadership from all three divisions agree college athletes should not be forced into an employment model. The Association believes change in college sports is long overdue and is pursuing significant reforms. However, there are some issues the NCAA cannot address alone, and the Association looks forward to working with Congress to make needed changes in the best interest of all student-athletes.”

2024 (March 5th) - immediately after the Dartmouth vote, the House Committee on Education & the Workforce’s Subcommittees on Health, Employment, Labor, and Pensions and Higher Education and Workforce Development announce a March 12th hearing is ironically titled "Safeguarding Student-Athletes From NLRB Misclassification"; the hearing is identical in context and purpose to a reactionary hearing in the same committee on May 8, 2014 after the regional director issued his decision in the Northwestern unionization case finding that Northwestern football players were employees and entitled to vote on whether to form a union; the 2014 hearing was likewise ironically titled “Student-Athlete Unions”

2024 (March 12th) - House Committee on Education & the Workforce’s Subcommittees on Health, Employment, Labor, and Pensions and Higher Education and Workforce Development hold a hearing ironically titled "Safeguarding Student-Athletes From NLRB Misclassification"; hearing is a frontal attack on athletes as employees, the NLRB’s policy on athletes as employees, and the NLRB’s Dartmouth decision; four witnesses testified, three against employee status and unionization and one in favor; Mark Gaston Pearce, the lone witness testifying in support of athlete labor rights is a former member of the National Labor Relations Board’s national panel; Mr. Pearce made a compelling affirmative case for athlete labor rights and dismantled NCAA/Power 5 talking points and fearmongering on the harm that employee status would cause

2024 (April 18th) - the state of Virginia passes a law that permits schools in Virginia to pay athletes directly for their NIL; the law conflicts with NCAA prohibitions on direct payments; the universities of Virginia and Virginia Tech were instrumental in getting the law passed; UVA athletics director Carla Williams said, "If this law gets us closer to a federal or a national solution for college athletics then it will be more than worthwhile. Until then, we have an obligation to ensure we maintain an elite athletics program at UVA."

2024 (April 29th) - rumors fueled by selective media leaks surface that the NCAA and Power 5 are in “deep discussions” on a settlement House, Hubbard, and Carter; few details are offered, but the basic structure would have the NCAA (not the Power 5 ) pay nearly 3 billion in damages, and the Power 5 would agree to future revenue sharing with athletes at a potential cost of $15-20 million per year; the scope of releases from liability—including future liability—are not disclosed; NCAA and Power 5 couple settlement talks with potential Congressional action that would further immunize the NCAA and Power 5 and prevent athletes from being employees of their university

2024 (May 8th) - House members Barry Moore (R-AL) and Russell Fry (R-SC) introduce a bill titled “The Protect the Ball Act” that contains sweeping antitrust immunity for the NCAA and Power 5; the bill is viewed as a complement to a potential global settlement of House, Hubbard, and Carter

C. New Dynamics from the Timeline

Below is a discussion of the new dynamics that have emerged over the last year that will likely influence the future of college sports.

1. Conference Realignment 2.0 and Big Ten-SEC Dominance

After Oklahoma and Texas left the Big 12 for the SEC in 2021, and UCLA and USC left the Pac-12 for the Big Ten in 2022, there was a lull in the second wave of football-driven conference realignment.

However, in August 2023, with the Big Ten’s acquisition of Oregon and Washington and the death of the Pac-12, college sports now have the Big Ten and SEC, then everyone else.

There will likely be another shakeout resulting in two super conferences that will operate like the NFL.

The Big Ten and SEC’s separation from the rest of college sports—including the Big 12 and ACC—is now official through the Big Ten-SEC “Advisory Group.”

The Big Ten and SEC have dispensed with the pretense of working through existing NCAA governance structures.

They are forging their own way on their own terms with little regard for the interests of other NCAA stakeholder groups.

While the Advisory Group’s agenda is purposefully vague, it seeks to address the possible settlement of pending antitrust cases and restructuring of NCAA governance.

The Big Ten and SEC have extraordinary influence over the future of college sports.

Key Players: SEC Commissioner Greg Sankey and Big Ten Commissioner Tony Petitti

2. The “New” NCAA and Charlie Baker’s Role

The NCAA’s claimed “representative democracy” is now officially dead.

NCAA governance boards, committees, working groups, and hand-selected athlete representatives are no more than window dressing for a decision-making process commandeered by the Big Ten and SEC and increasingly influenced by lawyers and lobbyists.

Baker has been portrayed as a visionary leader with fresh ideas. Some believe his “Project D-I” is a progressive model to bring NCAA rules and policy into alignment with the realities of the big-time football and men’s basketball products.

Baker’s proposal is poorly defined and has not been presented to stakeholders as a formal proposal. So far, it has been pitched merely as a “conversation starter.”

What little we know about his proposal suggests that its contours (e.g., “educational” trust fund revenue sharing) may align with a global settlement strategy for the pending antitrust suits.

But who has been and will be in those conversations?

Like every NCAA president in the post-Board of Regents era, Baker’s primary role is to act as a frontman for big-time football interests.

During the initial phases of conference realignment 2.0 in 2021 and 2022, Mark Emmert fronted for a five-conference cartel, the Power 5.

If history is our guide, Charlie Baker is now fronting for a two-conference duopoly, the Big Ten and SEC.

Key Players: NCAA President Charlie Baker, NCAA Board of Governors Chair/Division I Board of Directors member/Baylor University President Linda Livingstone, NCAA Board of Governors member/Chair of the Division I Board of Directors/University of Georgia President Jere Morehead

3. Congressional Activity (hearings and bills)

In the last year, Congress has held five hearings, all of them dominated by NCAA and Power 5 witnesses and promoting NCAA and Power 5 narratives.

That’s a hearing just over every two months.

In the same period, Senators and representatives have introduced or reintroduced ten bills or “discussion drafts.”

That’s a new legislative proposal every 36 days!

Seven of those bills align with NCAA and Power 5 interests.

This is an unprecedented level of congressional activity on college sports issues focused primarily on three specific issues: (1) preemption of state sports-related laws addressing athlete compensation, (2) antitrust immunity, and (3) making it impossible for athletes to be employees of their university.

Since 2020, when the NCAA and Power 5 began their assault on Congress, twelve hearings have occurred, mainly in Senate and House Committees with jurisdiction over (1) commerce, (2) the judiciary, and (3) employment and labor matters.

Why these three committees? Because these are the committees through which the NCAA and Power 5 would obtain preemption (commerce), antitrust immunity (judiciary), and no-employee status for athletes (employment/labor).

As the congressional campaign has evolved, the hearings and bills have subtly moved closer to NCAA/Power 5 interests and away from athlete interests.

That should not be surprising since the hearings have been dominated by NCAA/Power 5 witnesses. As shown in the DYK chart below, sixty-two witnesses have testified so far. Forty-four (71%) testified in favor of some form of protective federal legislation for the NCAA and Power 5. Only one Power 5 football or men’s/women’s basketball player—whose labors underwrite the entire college sports industrial complex—has testified.

It’s important to note that no bill provides for revenue sharing, and only one (Murphy-Sanders) would make athletes employees.

The NCAA and Power 5’s lobbyists have brilliantly manipulated the congressional debate to emphasize equity narratives, chief among them Title IX and gender equity.

Lawmakers, particularly women, have responded sympathetically to the lobbyists’ appeals.

While the congressional debate has been largely partisan, there is a potential bipartisan middle ground on equity issues.

Democrat women on the key Senate and House committees are prize targets of NCAA/Power 5 lobbying.

As NCAA and Power 5 lobbyists have leaned heavily into their no-employee campaign, Democrat women from traditionally labor-friendly states in the Midwest are the most valuable targets of all.

If the NCAA and Power 5 can secure just a few Democrat women from labor-friendly states to openly endorse legislation that prohibits athletes from being employees, their chances of getting such a bill increase substantially.

Representative Debbie Dingell (D-MI) is a perfect example. Dingell sits on the House Energy and Commerce Committee and its Innovation, Data, and Technology Subcommittee, which has held three hearings since September 2021.

Michigan is a labor-friendly state, and Ms. Dingell has built her political career in part by promoting labor issues.

For example, in 2020, Ms. Dingell was a leading advocate for the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, saying in a press release that “Unions fought for all of us to have a forty-hour work week, healthcare benefits, time off, safe workplace and many more critical benefits…[w]hen unions are strong, all workers benefit. We must strengthen workers’ right to join a union and have a voice.”

However, Ms. Dingell has expressed support for fellow Committee member Gus Bilirakis’ (R-FL) new bill, “Fairness, Accountability, and Integrity in Representation of College Sports Act” which contains a provision that makes it impossible for athletes to be employees of their university which means they cannot form a union (see January 11th Timeline entry above).

At the January 18, 2024, hearing in the Innovation, Data, and Commerce Subcommittee, Ms. Dingell appeared very sympathetic to the gender equity-based narratives used to promote the no-employee provision.

According to the lobbying disclosure reports for the third quarter of 2023, the NCAA’s lobbying firm, Brownstein and Hyatt, added Ms. Dingell’s former and long-time chief aid, Greg Sunstrom, to its lobbying team.

Coincidence?

Unlikely.

That is how granular, sophisticated, and cynical the NCAA’s lobbying campaign has become.

The NCAA and Power 5’s congressional campaign is focused on a small group of key lawmakers. Of the 535 members in both chambers, perhaps less than 50 will have substantial, perhaps controlling influence over the future of college sports.

Note on Key Players: For committees, the Chair is a member of the party that controls the chamber. The Ranking member is from the party that does not control the chamber. In the current Congress, Democrats control the Senate, and Republicans control the House.

Key Players:

a. Committee Chairs and Ranking Members

Maria Cantwell (D-WA) - Chair of Senate Commerce Committee

Ted Cruz (R-TX) - Ranking Member, Senate Commerce Committee

Dick Durban (D-IL) - Chair of Senate Judiciary Committee

Lindsey Graham (R-SC) - Ranking Member, Senate Judiciary Committee

Bernie Sanders (I-VT) - Chair of Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee (HELP)

Bill Cassidy (R-LA) - Ranking Member, HELP Committee

Cathy McMorris-Rodgers (D-WA05) - Chair of House Energy and Commerce Committee

Frank Pallone (D-NJ06) - Ranking Member of House Energy and Commerce Committee

Jim Jordan (R-OH04) - Chair of House Judiciary

Jerry Nadler (D-NY12) - Ranking Member House Judiciary

Virginia Foxx (D-NC05) - Chair of House Committee on Education and the Workforce

Bobby Scott (D-VA03) - Ranking Member House Committee on Education and the Workforce

b. Other Prominent Voices on College Sports Issues

Sen. Roger Wicker (R-MS)

Sen. Jerry Moran (R-KS)

Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL)

Sen. Tommy Tuberville (R-AL)

Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN)

Sen. John Thune (R-SD)

Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV)

Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT)

Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT)

Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ)

Rep. Gus Bilirakis (R-FL)

Rep. Jeff Duncan (R-SC)

Rep. Buddy Carter (R-GA)

Rep. Lori Trahan (D-MA)

Rep. Debbie Dingell (D-MI)

c. Prize Swing Votes for NCAA/Power 5

Approximately 24 Democrat women from the key six committees in both chambers are persuadable on NCAA/Power 5-friendly legislation.

Some have proven susceptible to NCAA/Power 5 equity-based narratives and/or represent states in the Big Ten or SEC that have powerhouse football programs.

There are a number of Democrat men from Big Ten and SEC states that could likewise support an NCAA/Power 5-friendly bill, but Democrat women have been the target of NCAA/Power 5 lobbying.

If there is a global settlement of pending antitrust cases (House, Hubbard, Cater, Ohio et al., Tennessee et al.) that is perceived to have addressed most athlete compensation issues and some regulatory issues, the NCAA and Power 5’s congressional campaign for a preemption and no-employee bill becomes far more palatable to lawmakers.

4. Litigation Activity

Various stakeholder groups have filed six lawsuits and one agency action in the last year. That’s a suit/action every 52 days.

Moreover, in the same timeframe, two preexisting suits—Johnson and House—have progressed to critical litigation points.

This litigation activity is unprecedented in college sports and has reinforced the perception that the walls are closing in on the NCAA and Power 5.

It has also created a perception of chaos and uncertainty that has many institutional stakeholders panicked.

Yet, from the standpoint of chessboard management, the current legal and regulatory environment also provides the NCAA and Power 5 opportunities to limit or eliminate the greatest threats to their regulatory and business models.

Historically, the NCAA and Power 5 have been brilliant at taking what appeared to be existential threats to their regulatory supremacy and amateurism-based compensation limits and turning them into a net victory.

For example, in 2014 and 2015, a similar chaotic environment existed, with many in the sports commentariat predicting the death of amateurism and perhaps the death of the NCAA.

The NCAA faced external threats in O’Bannon (NIL), Alston (all compensation limits), and Northwestern (NLRB unionization), all portrayed in the media as the case(s) that would end the amateurism model. In addition, the NCAA was reeling from egregious missteps in the Penn State (Jerry Sandusky) and Miami (booster payments) cases that led many to wonder if the NCAA could survive.

The Power 5 used this unstable legal and regulatory environment to further segregate their interests from the rest of the NCAA through Autonomy legislation. This legislation permitted the Power 5 conferences to legislate in certain areas—including raising the compensation cap through the full cost of attendance scholarship—without permission from the membership.

Autonomy not only provided the Power 5 more legislative freedom, but the benefits they could offer through Autonomy—that other schools could not afford—gave the Power 5 an insurmountable advantage in recruiting.

Ultimately, the O’Bannon rulings turned out to be more favorable to the NCAA than to athletes, the Alston case was neutralized by amateurism-based protections from O’Bannon, the Northwestern case was iced by the National NLRB panel, and the NCAA survived the Penn State and Miami controversies.

On the back end of these “existential” threats, the NCAA and Power 5 landed in a better position than before.

The current litigation chaos is different from the 2013-2014 era in two important respects.

First, the number of threats is unlike anything we’ve seen in college sports, and they cover nearly every current vulnerability to the NCAA/Power 5 regulatory and business models, such as NIL compensation (House), Alston education benefits (Hubbard), all compensation limits (Carter), employee status (Johnson and Dartmouth), NIL recruiting inducements (Tennessee et al.), transfer limits (Ohio et al.), NIL collective payments, Title IX (Schroeder), and conference realignment (ACC/FSU).

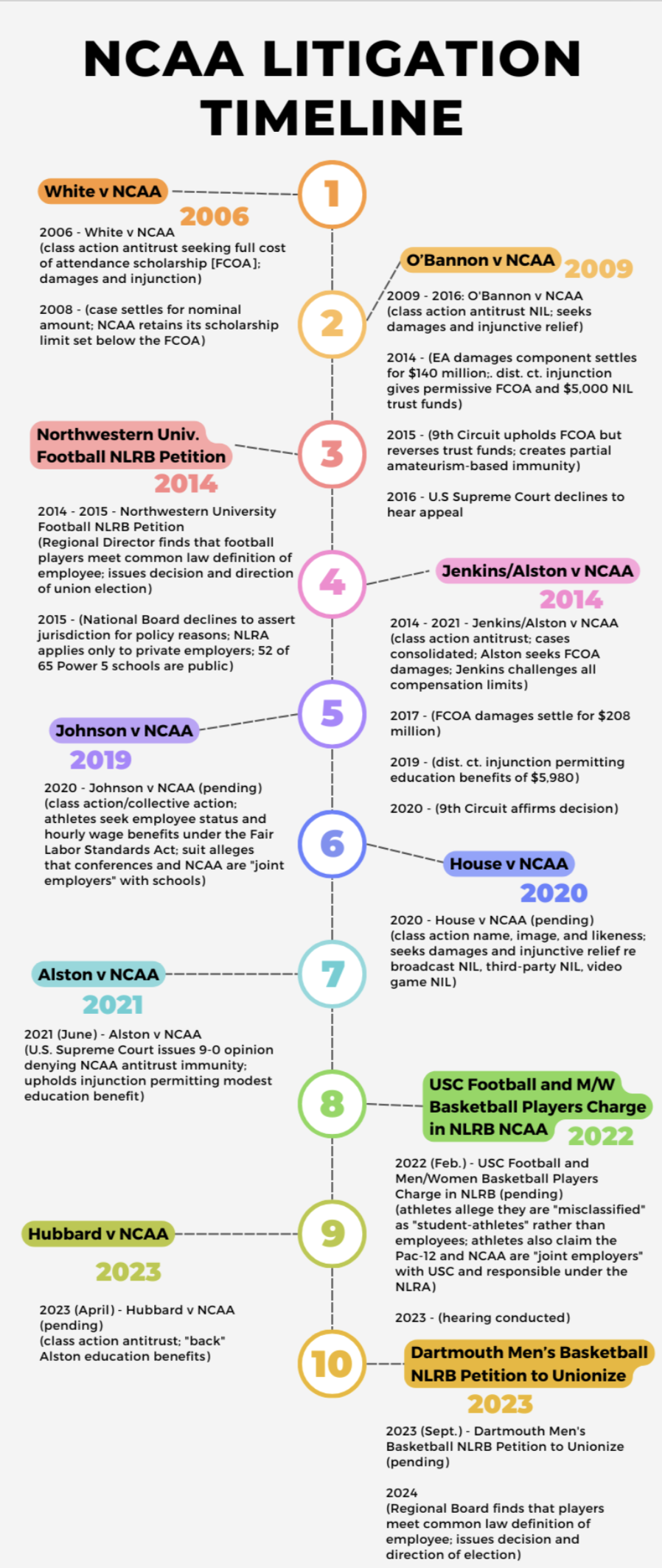

The DYK litigation timeline below shows the progression of key cases/actions from White (2006) to Tennessee (2024). The number and scope of cases in 2023 and 2024 is breathtaking.

Second, in 2014, the NCAA did not have a strategic lobbying campaign. They hired their outside lobbying firm, Brownstein Hyatt, in 2014; however, neither the NCAA nor the Power 5 had a comprehensive congressional strategy.

Today, the NCAA and Power 5 have a sophisticated and specific congressional campaign that is intimately woven into their litigation strategies.

The two forums have played off against each other, manipulated by the NCAA and Power 5 to achieve their ultimate objectives: regulatory supremacy and control of the labor force in Power 5 football and men’s basketball.

That is why it is so important for athletes and other stakeholders to understand the potential implications of a dual Congress-litigation strategy, which may provide the NCAA and Power 5 with everything they have wanted since they launched their congressional campaign in 2019.

A global settlement of the antitrust suits addressing athlete compensation, NIL, and transfers would solve many of the NCAA’s problems. It would likely provide the NCAA and Power 5 with sweeping releases from liability in the compensation cases, essentially creating a form of antitrust immunity.

Similarly, the NIL recruiting inducement and transfer antitrust cases—which do not seek damages—could result in negotiated or court-ordered injunctive relief that is acceptable to the NCAA and Power 5 and would set the regulatory landscape and protect it from future challenges.

If those issues are resolved in the litigation setting, you can be certain that the NCAA and Power 5 will use those settlements in Congress to finish off the athletes’ rights movement through a bill that provides preemption of state laws and non-employee status for athletes.

As Jeffrey Kessler (lead attorney for athletes in House, Hubbard, and Carter) said in a December 8, 2023, podcast interview:

I think the one thing that might help [the NCAA] with Congress in the future is reaching an antitrust settlement with us…because if the antitrust claims are resolved and approved by the court as fair and reasonable to the classes, both the past damages and then going forward, then it's much easier for Congress to think about the rest of it, right?

While Kessler hasn’t divulged what settlement terms he would accept, he suggested the bar would be set quite high.

Even if a global settlement doesn’t occur, athletes should understand and be prepared for this scenario, particularly the NCAA and Power 5’s engagement with Congress after or in tandem with any global litigation settlement(s).

The possibility of congressional action post-settlement is particularly important on the no-employee issue, which would forever prevent athletes from organizing and engaging in collective bargaining under the NLRA and permanently extinguish all other labor rights that require employee status.

Key Players:

a. Athlete Attorneys

Jeffrey Kessler and Steve Berman ( House, Hubbard, and Carter)

b. NCAA/Power 5 attorneys (dozens from multiple firms)

c. Judges

Ten total. In the short run, the most influential will be Claudia Wilken (House, Hubbard), Richard Seeborg (Carter), and three Third Circuit judges (Theodore McKee, David Porter, Felipe Restrepo) who will decide whether athletes can pursue employee status under the Fair Labor Standards Act (Johnson).

d. NLRB National Board members

Four total, but there is one vacancy. Members are Lauren McFarren (Chair), Marvin Kaplan, David Prouty, and Gwynne Wilcox.

e. NLRB General Counsel and Deputy General Counsel

Jennifer Abruzzo (General Counsel) and Peter Ohr (Deputy General Counsel)

II. Athlete Action and Reasonable Requests

Given the unique features of the current legal and regulatory landscapes, we offer a summary of goals that athletes may consider and pursue to increase their chances of having a meaningful say in the future of college sports.

A. Understand the Issues!

Education is job one for athletes.

The more athletes know, the more powerful their voice.

It’s important to understand that most institutional stakeholders have little knowledge of the structure, regulation, and business of college sports.

It’s our belief that if you got all Power 4 university presidents, athletics directors, and coaches in the same auditorium and gave them a pop quiz on basic elements of what is happening right now in Congress, federal courts, administrative agencies, and state legislatures, most would fail.

It’s also unlikely that these stakeholders and decision-makers could identify a single law, lobbying, or public relations firm currently working on their behalf.

The extent of stakeholders’ knowledge is limited to whatever talking points memos they have received from the NCAA and Power 4 motherships. These memos are loaded with false narratives and fearmongering, and most of them are written by lawyers, lobbyists, and spin doctors.

With just a little effort and motivation, athletes can easily surpass the knowledge base of the people who profess to be the “experts” acting in athletes’ best interests.

Similarly, athletes should be wary of accepting as true the latest Tweet or article from sports media outlets that are making billions from the status quo.

That’s why DYK uses and makes available original source material to inform athletes’ thinking and conclusions.

Our content, suggestions, and conclusions are based on those materials, not how someone else characterizes them.

B. Demand to be Heard!

Athletes have the same right as any American to be heard in the forums that determine their rights and futures.

In Congress, the NCAA has used hand-selected athletes and NCAA-controlled student advisory committees to speak for all athletes.

In many of the congressional hearings, letters from NCAA and conference student-athlete advisory committees have literally been held up, read aloud, and introduced into the record as evidence of athlete “consensus” on the need for protective federal legislation (preemption, antitrust immunity, non-employee status) that perfectly aligns with NCAA and Power 5 regulatory and business goals.

Is it a coincidence that these letters get moved to the front of the line and become priority documents in Congress?

Are these letters the sole work product of the students who submitted them, or have they been vetted by NCAA/Power 5 lawyers and lobbyists?

This is the perfect time for athletes whose voices have been marginalized to send their letters to Congress.

Athletes from states that have lawmakers engaged in the debate (see the list above) should reach out to them and begin a thoughtful dialogue on how they see the key issues in college sports.

Athletes should ask tough questions and press for clear answers.

They could do the same with NCAA leaders, college presidents, conference commissioners, athletics directors, and any other institutional decision-makers.

As discussed in the section below, athletes are on solid ground, asking for access to the same information that has reached their elected representatives through NCAA lawyers, lobbyists, and spin doctors.

C. Ask Congress, the NCAA, and the Power 5 to Suspend Further Congressional Activity Until Athletes Have Access to the Same Information and Documents as NCAA/Power 5 Lobbyists and Spin Doctors

While we believe that Congress and the federal government should stay out of college sports, the fact remains that Congress is involved.

Athletes did not go to Congress; the NCAA and Power did.

An honest assessment of the progress the NCAA and Power 5 have made in their five-year campaign to eliminate athletes’ rights suggests that some form of federal intervention at some point in the future is likely, regardless of whether the NCAA and Power 5 try to apply a band-aid through NCAA changes like Charlie Baker’s D-I Project.

Athletes are on the clock, and they don’t even know it.

They could ask Congress to call a time-out.

Athletes could reasonably ask Congress to suspend any further hearings or discussions of federal legislation until athletes are afforded access to all NCAA/Power 5 lobbying and public relations communications and work product.

At this critical juncture in college sports, Congress should use its powers to inform the debate over college sports regulation, not obscure it through narratives ginned up by NCAA/Power 5 lobbyists and spin doctors.

Athletes should know as much about the NCAA and Power 5’s congressional and public relations campaigns as their lobbyists and spin doctors.

After all, those lobbyists and spin doctors are paid from revenue generated by athlete labor.

The NCAA and Power 5 justify their need for absolute regulatory authority in part on the need to preserve a “level playing field” in college sports.

Yet, in their unprecedented congressional campaign for extraordinary federal protections and immunities, the NCAA and Power 5 are playing on a rigged field heavily slanted in their favor.

Athletes are entitled to a level playing field regarding the information that has reached Congress through NCAA and Power 5 backchannels.

Hearings could resume once those materials are provided and athletes are assured of meaningful input into the legislative process.

If the NCAA and Power 5 refuse to release the documents, Congress should subpoena them.

Division I men’s basketball players have special standing to seek lobbying and public relations materials commissioned by the NCAA.

The entire NCAA bureaucracy is funded by March Madness revenue, including its legal, lobbying, and public relations expenses.

Because of the Board of Regents case in 1984, Power 5 football keeps its money to itself and doesn’t contribute to NCAA expenses.

Thus, men’s basketball labor pays all of Brownstein Hyatt’s (NCAA outside lobbying firm), the NCAA Office of Government Relations Office’s, and Bully Pulpit Interactive’s (NCAA public relations firm) fees and expenses.

Since 2015, men’s basketball players have paid Brownstein, the NCAA Office of Government Relations, and Bully Pulpit at least $50 million dollars combined.

The NCAA cannot, in good faith, claim exclusive “ownership” of these experts’ work products.

The NCAA’s congressional campaign against athletes’ interests has been ongoing for nearly five years.

In that time, Congress could have established, as a precondition to any bill regulating college sports, a truly independent body to thoroughly and objectively explore all of the issues facing college sports.

That body could have utilized subpoena power to compel NCAA and Power 5 documents and testimony that would shed light on the truth of the business model and the NCAA and Power 5’s true motivations in seeking protective federal legislation.

That option is likely unfeasible now, given the evolution of the NCAA/Power 5 congressional campaign and external regulatory pressures from federal courts, administrative agencies, and state legislatures.

However, at the very least, Congress could insist that the NCAA and Power 5 open their lobbying and public relations files to athletes and pledge to include a truly representative swath of athletes to inform Congress’ work going forward.

If, as the NCAA and Power 5 contend, their congressional campaign is designed to promote and protect athlete interests, they should be eager to share information and documents with athletes.

D. Request Notice of and Input on Any Global Legal Settlement(s)

Before the NCAA and Power 5 permanently settle away athletes’ rights in the pending athlete compensation antitrust suits (House, Hubbard, and Carter), athletes should be afforded a thorough, plain explanation of the specific terms of any such settlement(s) and a non-litigation opportunity to be heard.

While there is a process within the lawsuit for class members not serving as class representatives to object to the terms of a settlement, those objections occur well into the settlement approval process. The momentum toward settlement is already fixed by that point, and objections are rarely successful.

Given the magnitude of potential settlement issues, athletes impacted by the settlement(s) could rightly request a public vetting of the terms and long-term consequences of any settlement(s).

Athletes could also ask the DOJ’s Antitrust Division or the Federal Trade Commission to scrutinize and comment on any settlement.

This is a particularly pressing issue if the NCAA and Power 5 use a global settlement on compensation issues as a new justification for federal legislation on preemption and non-employee status for athletes.

The global settlement option is not a routine process with pedestrian impacts. It could be one of the most consequential legal settlements in American sports history and may permanently alter athletes’ legal rights going forward.

Under these circumstances, any settlement(s) should be carefully and publicly scrutinized. The settlement approval process should be more than a rubber stamp from a district court judge.

Moreover, across the three pending compensation cases, there is not a Power 5 men’s basketball player among the “class representatives” who stand as proxies for class members. The class representatives include (1) a Power 5 swimmer, (2) a Power 5 women’s basketball player, (3) three Power 5 football players, (4) a Power 5 women’s track athlete, and (5) a Power 5 women’s soccer player.

The absence of a Power 5 men’s basketball player is noteworthy.

As discussed above, the NCAA has paid the legal fees and settlements in prior class action antitrust suits from men’s basketball revenue. So far, Power 5 football money hasn’t absorbed these massive expenses, which means Power 5 football has gotten a free ride.

Revenue from March Madness money will likely be the primary funding source for any global settlement.

The athletes who generate that revenue should have representation in discussions over litigation strategy, including settlement talks and terms.

In the House suit, the NCAA opportunistically (and disingenuously) raised the absence of a men’s basketball player as a class representative in opposition to the athletes’ motion to certify the damages class (without addressing the unique role men’s basketball plays in underwriting the NCAA administrative state and paying NCAA expenses).

The court dismissed the NCAA’s argument, finding that the class representative who is a football player was an adequate representative of men’s basketball interests because he had friends on the men’s basketball team.

E. Ensure Future Collective Bargaining and Other Labor Rights Are Not Compromised

Athletes should be prepared to coordinate and mobilize an aggressive campaign in Congress (and state legislatures) to ensure that no laws are passed that would make it impossible for athletes to achieve employee status, Employee status is a prerequisite to protections under the National Labor Relations Act and other federal and state labor laws.

The current debates over employee status in Congress have been framed around whether athletes should be employees, not whether they are.

Under the “should” narrative in Congress, there is only one answer: No, hell no!

However, that narrative is built upon college sports’ mythologies of amateurism and the “student-athlete,” not a factual inquiry into whether athletes meet well-settled legal definitions of employee as a matter of fact.

The determination of whether athletes are employees should be in the hands of employment experts at the NLRB, the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division, and federal courts, not poorly informed lawmakers who have been manipulated by NCAA and Power 5 lobbyists.

At the March 12, 2024, hearing, Mark Gaston Pearce, former member of the NLRB’s national board, educated the Subcommittee on the history of the term “student-athlete.”

He was the first expert witness to testify on the issue over four years and twelve hearings.

Pearce explained that contrary to its common use as an expression of the “integrity” and educational value of college sports, the term “student-athlete is a cynical phrase invented by NCAA president Walter Byers and NCAA lawyers in the 1950s to avoid legal liability for workers’ compensation benefits.

In his 1995 book Unsportsmanlike Conduct: Exploiting College Athletes, Byers admitted the true purpose of the term.

Despite its undisputed history and purpose, the term “student-athlete” as a moral principle has become so deeply embedded in people's thinking about the legal status of athletes that it is virtually unchallengeable.

Its use has tricked athletes into believing they have no protectable legal rights.

The NCAA and Power 5 have propagandized the concept of the “student-athlete” to mean the legal opposite of employee.

That is why the NLRB’s General Counsel, Jennifer Abruzzo, issued a crucial policy memo in September 2021 that said athletes had been unlawfully “misclassified” as non-employees.

In her memo, Ms. Abruzzo refused to use “student-athlete” because its very utterance leads athletes to falsely believe they can’t seek the protections of labor laws (“While Players at Academic Institutions are commonly referred to as ‘student-athletes,’ I have chosen not to use that term in this memorandum because the term was created to deprive those individuals of workplace protections.”)

Collective bargaining under the NLRA is the only way athletes can force schools, conferences, and the NCAA to grant them a seat at decision-making tables to protect their rights and dignity in the workplace.

The NCAA and Power 5’s claim that employee status will be the death of college sports is grossly exaggerated. Employee status and the existence of an athlete union don’t guarantee that athletes will get what they want. But it will guarantee that they have a right to seek it with legal protections.

Negotiations will be university and conference-specific. What Dartmouth basketball players may realistically obtain through collective bargaining is not what Ohio State football players may obtain.

At Dartmouth, for example, the men’s basketball team’s collective bargaining goals will likely be informed by Dartmouth's precedent for student worker unionization.

Dining hall student workers recently unionized to address work conditions and compensation. They bargained for more control over their schedules and increased their hourly wages (to $20 per hour).

These are modest improvements that haven’t caused disruptions to Dartmouth’s normal operations.

If the men’s basketball players ultimately achieve something similar, will it substantially impact Dartmouth’s institutional interests and operations or motivate other similarly situated athletes at other schools to petition for a union?

Will other Ivy League basketball teams follow suit?

Who knows?

Even with employee status, unionization can only occur if athletes choose to pursue a petition for unionization and then vote to form a union.

Importantly, since it was first filed in September 2023, the Dartmouth case has yet to produce the predicted “domino effect” of NLRB union petitions.

Labor markets are guided by market principles that limit overreach and unreasonable labor requests in the collective bargaining process.

Unionized labor forces across hundreds of industries and millions of workers have found market equilibrium and labor peace through collective bargaining.

Why should it be any different for college athletes and their employers?

Will there be challenges in organizing athlete labor markets?

Of course, but that shouldn’t be a deterrent to change.

The Dartmouth case should not be used as a justification to permanently close the door on potetntial unionization for Power 5 profit athletes who may choose to bargain with their instituions—and perhaps conferences and the NCAA—on much more substantive issues like health and safety, revenue sharing, schedule control, coach-player relations, and notice and input on decisions that impact athletes’ lives.

The NCAA and Power 5 have consistently argued that issues around employee status and potential unionization—as well as “NIL compensation”—are too complicated to solve, so we should default to an NCAA-Power 5-controlled status quo that limits or prohibits them.

That is a pessimistic way to think about solving big issues.

In 1990, international scientists announced the formation of the Human Genome Project, a massive, unprecedented quest to map the entire human genome. Originally scheduled to take at least fifteen years, scientists substantially completed the map in 2003, two years ahead of schedule.

The success of the Human Genome Project now stands as one of the greatest scientific feats in human history.

Through decades of debate and litigation over athlete compensation models and the proper legal relationship between athletes and institutions, the NCAA and Power 5 want Congress, federal courts, administrative agencies, state legislatures, and the American public to believe that meaningful college sports reform, including employee status, are unsolvable.

F. Public Disclosure and Open Records/Meeting Requirements

Athletes could also reasonably request that the NCAA, Power 5, and member institutions:

1. Make mandatory public disclosures of financial information much broader than Form 990 tax returns or EADA financials.

2. Be subject to open records requests.

3. Have certain governance and infractions and enforcement proceedings subject to open meeting requirements.

These requirements could be made enforceable through collective bargaining or Congress.

Regarding open meetings, the NCAA and conferences should:

a. make open to the public all meetings of all governing boards/committees;

b. reasonable criteria for what constitutes an official “meeting” to prevent secret off-the-books meetings immune from scrutiny;

c. prohibition on the use of disappearing apps or other technology that hides or eliminates written records;

d. make open to the public all infractions hearings;

e. publish all infractions and enforcement materials (Notice of Allegations, Responses, notice of hearings, hearing transcript) on the NCAA website;

f. athletes impacted by an enforcement action will have a right to appear and speak at any infractions and enforcement proceedings.

G. Audits

Athletes (and Congress) could ask that the NCAA national office and all Power 5 conferences be subject to financial audits by auditors selected by athletes and reporting to athletes and their representatives.

The audits should include an initial, comprehensive forensic financial and operational accounting of the NCAA national office and conference entities that meet certain revenue thresholds and recurring, less rigorous audits thereafter.

The auditor would make public all audit results.

The NCAA national office should be an audit priority. From Form 900 tax returns and consolidated financial statements, it is impossible to know exactly where and how the NCAA spends athlete-generated money.

Several of its Form 990 “Functional Expense” line items are vaguely defined and have hefty price tags. The NCAA spends hundreds of millions of dollars each year for “NCAA Championships” and “Travel and Occupancy.”

Athletes and stakeholders should know much more about how that money is actually spent.

Similarly, the use of special, segregated funds that siphon off massive piles of money needs scrutiny.

For example, in 2022, the NCAA created the “1910 Collective” as a risk management device. The Collective is essentially a captive self-insurance fund. Since its inception, the NCAA has allocated approximately $200 million to the Collective.

While the NCAA’s consolidated financial statements disclose the fund's existence, its description is cryptic, and it’s not clear who controls the money or how it is or can be spent.

The IRS appears to have little curiosity about NCAA finances.

The NCAA’s lobbying and executive salary expenditures are begging for an independent audit.

The NCAA has made lobbying for federal protections and immunities a top institutional priority, yet it reports only modest lobbying expenses on its Form 990, well within the IRS “expenditure test” limit of $1 million.

Similarly, NCAA executive salaries are not defensible in the nonprofit world, and they are escalating. Seven-figure golden parachute agreements/payouts should also be analyzed.

H. Get Ahead of the Next Massive Revenue Streams

The broader college sports marketplace is poised for massive new revenue streams in athlete data collection, new AI fan engagement technologies, and sports betting that could result in billions of additional dollars flowing into the system.

Before the NCAA, Power 5, and other institutional interests lay exclusive claim to those revenue streams, athletes should consider and have input into how that money is spent.

The NCAA has already laid the foundation for exploiting the data collection market tied to sports betting. In fact, the NCAA and the Mid-American Conference are already in data deals with Genius Sports, a leader in the exploding sports betting data collection market.

Much of the data that companies like Genius covet is athlete data.

New AI technologies may use athlete intellectual property to create custom engagement content for small groups of consumers or even individual consumers.

Similarly, sports betting revenues are exploding as more states jump into the market.

States are already spending that money in ways that do not benefit the sports and teams that generate betting volumes.

These revenue streams could be used to offer innovative solutions to the NCAA/Power 5 claims that there simply isn’t enough money in the system to address all athlete compensation, equity, and well-being interests.

Note: We will be doing a Deep Dive series on sports betting in the near future

III. The Likely NCAA/Power 5 Response

Undoubtedly, NCAA, conference, and institutional interests will mock these reasonable requests as absurdities they will not even consider, much less agree to.

And that’s the problem.

True transparency and accountability are so far outside the experience and comprehension of most in-system decision-makers that they cannot imagine a world where athletes have a truly equal voice and access to information.

That is the Pendulum Problem, explained in Section III. Most stakeholders start with the red ball from the 1950s, not the true equilibrium point represented by the black ball.

And that’s where collective, well-informed action comes in.

With a unified voice, athletes can do what the NCAA, Power 5, institutions, Congress, courts, legislatures, agencies, and reform movements have failed to do through decades of “debate”: achieve meaningful change.