XII. Other State Laws

Revenue Sharing

Some states have introduced or discussed revenue sharing bills that would allow athletes in sports that generate net revenue to receive distributions if certain conditions are met. A federal law (Athletes’ Bill of Rights”) had a similar component that was later removed.

Revenue sharing bills are built around an equity-based philosophy that athletes should be able to share in the fruits of their labor. This is a fundamental American value that drives our free enterprise system.

However, the NCAA and Power 5 have aggressively opposed revenue sharing laws as existential threats to college sports.

Thus far, no revenue sharing proposal—state or federal—would make athletes employees of their university.

Two recent California proposals tested the political viability of revenue sharing: (1) the “California Race and Gender Equity Act” (February 24th, 2022) and (2) the “College Athlete Protection Act” (January 19th, 2023).

The response to these bills suggests that lawmakers are not yet prepared to view the interests of profit athletes in Power 5 football and men’s basketball through the lens of basic American economic liberties.

a. California Race and Gender Equity Act

California state Senator Steve Bradford introduced this bill in 2022. Bradford was an original co-sponsor of SB 206. In conjunction with Ramogi Huma, Executive Director of the National College Players Association (NCPA), Bradford crafted the bill to permit revenue-sharing for athletes at California schools that have revenue that exceeds expenses in a given sport.

If a sport had net revenue in a season, fifty percent would be put aside for possible distribution to athletes in that sport. The other fifty percent would flow into the athletics department budget as usual.

Distributions would be put into an athlete trust fund each year. Athletes could receive distributions only after completing their degree requirements, tying the money to an educational purpose.

As a practical matter, the only sports that consistently generate net revenue are Power 5 football and men’s basketball. The athletes in these sports are disproportionately African American.

Bradford and Huma framed the bill’s policy through a civil rights lens.

The Senate Education Committee and Judiciary Committees held hearings on the bill. Both Committees had mild philosophical support for the notion that the business model exploited African American athletes in big-time football and men’s basketball. However, the debate devolved into an “equity” stand-off between the rights and interests of black profit athletes and female athletes.

Power 5 schools in California launched an aggressive behind-the-scenes lobbying campaign to convince legislators that if profit athletes in football and men’s basketball were fairly compensated for the value of their labor, there would be a corresponding decrease in money available to fund women’s and “Olympic” sports.

While Bradford’s bill was voted through the Education and Judiciary Committees, it hit a buzzsaw in the Senate Appropriations Committee.

Appropriations sent the bill into its “suspense file,” the California equivalent of legislative limbo. Theoretically, it could have been voted out of the suspense file and made it to the floor of the Senate, but it did not.

After the bill’s demise, Bradford said it was torpedoed by “fears and disinformation” from universities opposing it, including UCLA and USC.

He cited gender equity “fearmongering” as the prime culprit.

b. College Athlete Protection Act

In January 2023, California Assemblymember Chris Holden introduced a bill similar to Bradford’s.

Holden’s bill would pay qualifying athletes up to $25,000.00 per academic year. The funds would be put into trust and made available when an athlete graduates.

The bill also contains health and safety standards, financial and life skills training, and a degree completion fund.

Importantly, the bill also prohibits California schools from reducing athletics scholarships or eliminating sports as of the 2021- 2022 academic year.

The NCAA jumped into the fray in April, condemning the bill. Tim Buckley, NCAA Senior Vice President of External Affairs (former key political aid to NCAA President Charlie Baker), said:

“It [Holden’s bill] will only further complicate an already murky picture while we’re working with Congress to create a uniform playing field in this space. I think we’ll see something emerge on the Senate side. Another state law at this time is not the right fix.”

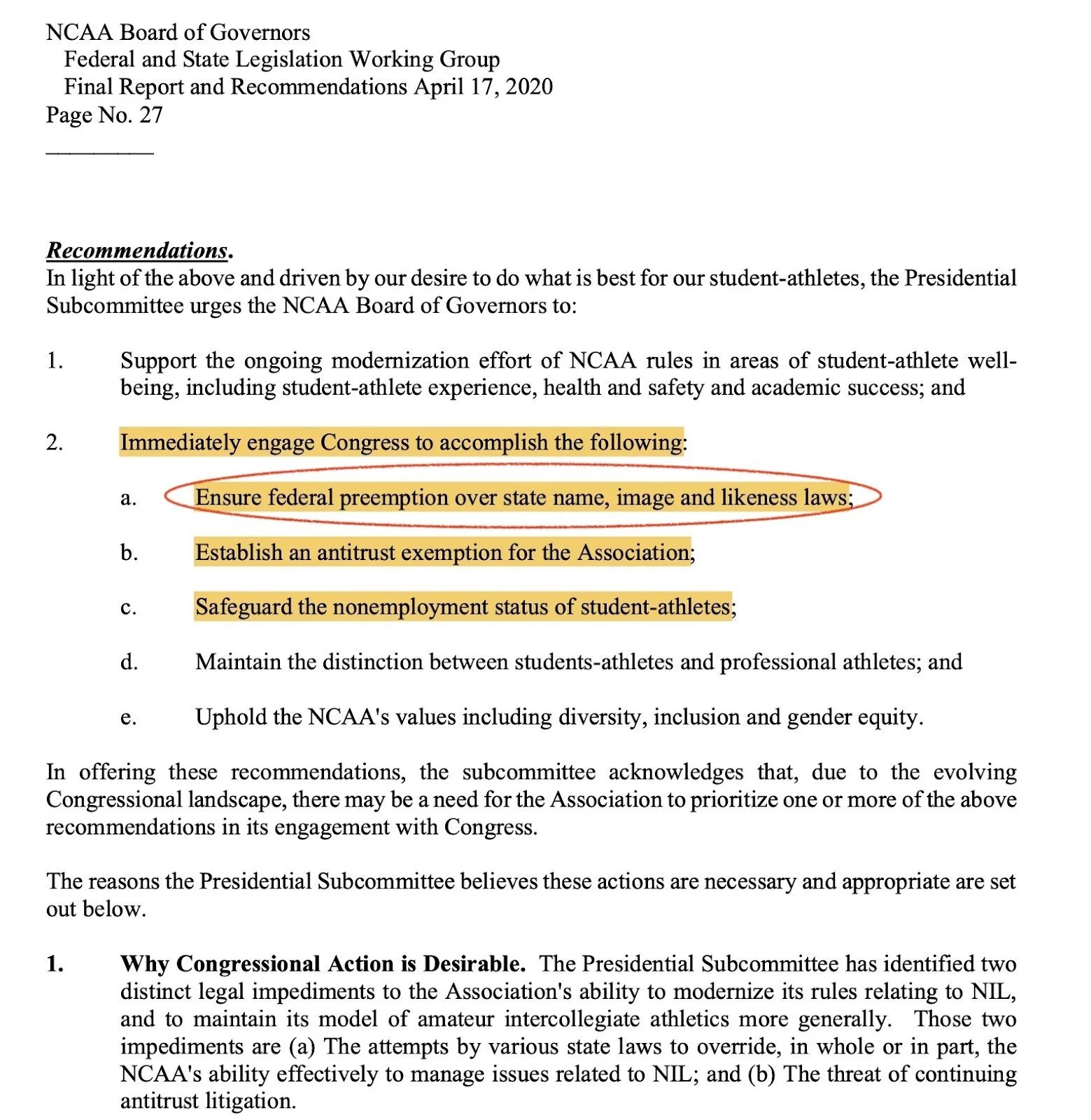

Buckley’s comments are revealing. The way to create a “uniform playing field” is through federal preemption. Since 2019, the NCAA and Power 5 have sold to Congress and stakeholders that they seek preemption only for state name, image, and likeness laws.

The Holden bill has nothing to do with NIL. Yet the NCAA and Power 5 want a sweeping preemption bill to wipe it off the map.

Buckley argued that Holden’s bill “would direct funds away from Olympic sports and women’s sports.” Buckley estimated that these athletes comprised 90 % of college athletes in California.

Holden’s bill made it through the Assembly content committees and was passed narrowly by the full Assembly on June 1st, 2023.

The California Assembly has 80 members. The vote was 42 “yes” and 38 either “no” (15) or “abstain” (23).

However, it appears that the same special interests that killed the Bradford bill stalled the Holden bill.

Holden’s bill had been scheduled for debate in the California Senate’s Education Committee on July 5th, 2023,

The same day, Holden and Huma announced the bill’s postponement until 2024.

Holden has been mum on why he pulled the bill, but media coverage suggests it may have been politically unviable because of the perceived harm it may cause to female and Olympic sports athletes.

In Congress, Sens. Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) reintroduced the College Athletes Bill of Rights on August 3rd, 2022, without a revenue-sharing provision.

At a May 2022 forum on college sports issues, Sen. Booker suggested that the revenue sharing component of the prior Athletes’ Bill of Rights was not politically viable due to gender equity concerns.

c. Observations from the California Revenue Sharing Bills

The California revenue sharing bills provide essential insights for broader discussions on athletes’ rights, particularly in Congress.

When lawmakers are faced with a false choice between the rights and interests of profit athletes in football and men’s basketball on the one hand and the rights and interests of “Olympic” and female athletes on the other, many err on the side of protecting Olympic sport/female interests.

The lobbying themes and tactics that scuttled the California revenue sharing proposals are the same currently employed by the NCAA and Power 5 in their Congressional campaign. The removal of the revenue sharing component of the College Athletes Bill of Rights speaks to the power of these tactics.

Second, lawmakers appear to have bought into the false premise that nonrevenue and women’s sports must be funded principally through football and men’s basketball revenue.

Third, the debate over athletes’ rights is partisan, with Republican decision-makers uniformly aligned with NCAA and Power 5 interests and Democrat decision-makers more aligned (but not entirely) with athlete interests.

It’s also important to note that the California legislature is considered the most “progressive” state legislative body on athletes’ rights in America.

i. False Financial and Equity Binaries

The aggressive opposition to the California revenue sharing proposals by status quo stakeholder interests is based on the false belief that stakeholders and decision-makers must choose between the interests of profit athletes in football and men’s basketball and those of Olympic sports athletes and female athletes.

This false choice assumes zero-sum financial and zero-sum equity worlds in college sports.

In-system stakeholders made identical arguments to oppose the current NIL market. They suggested that NIL payments to star football and men’s basketball athletes would “displace” revenue that would otherwise go to athletics department budgets, resulting in the elimination of nonrevenue athletics scholarships or entire sports.

The NIL market has not resulted in the fatal collapse of Olympic and women’s sports or the reduction of scholarships in those sports.

On the contrary, female athletes have thrived in the new NIL era. At the same time, college sports revenues have increased across the board in a historic bull market.

Conspicuously absent from the legislative debates on NIL and revenue sharing is any evidence of the financial and equity harms identified by opponents.

Through twelve ostensibly NIL-driven congressional hearings since February 2020, no Title IX or sports economics expert has been called to testify. Five of those hearings were held after the NIL market began in July 2021.

Similarly, in the revenue sharing debates in California, no Title IX or sports economics experts have weighed in.

Decision-makers have been influenced by well-polished prophecies of doom from some of the best lobbyists in America.

These false financial and equity binaries have forced legislators into moral dissonance.

At an April 26th, 2021, hearing in the California Senate’s Judiciary Committee hearing on the Bradford bill, Sen. Anna M. Caballero (D) perfectly captured the equity-themed dissonance of many Democrat women on athletes’ rights.

In her comments and questions to Sen. Bradford, Sen. Caballero openly wrestled with what she perceived as irreconcilable tension between revenue sharing for profit athletes in football and men’s basketball and potential harm to nonrevenue athletes, particularly women. (see video clips below)

Sen. Caballero applauded the bill’s educational focus and recognized the inequities in the system for profit athletes in football and men’s basketball. Still, she was instinctively drawn to the claimed injustices that may result for female athletes in sports that do not generate net revenue.

Importantly, Sen. Caballero pointed to the “comments in opposition from people that work in the university system” relating to Title IX and gender equity that influenced her thinking on the bill.

While Sen. Caballero voted for the bill, it was deep-sixed in the Appropriations Committee’s “suspense file” several days later.

Sen. Maria Durazo (D) echoed Sen. Caballero’s concerns, framing them around the potential “unintended consequences” of the bill.

The concerns raised by Sens. Caballero and Sen. Durazo on the Bradford bill subtly incorporate a utilitarian theme openly endorsed by the NCAA in its lobbying campaign in Congress.

That is, in a conflict between the interests of the “many” (nonrevenue and female athletes) and the “few” (profit athletes in football and men’s basketball), the interests of the many should prevail.

At the January 12th, 2023, NCAA convention, NCAA President Charlie Baker and NCAA Board of Governors Chair Linda Livingstone made that very argument. They openly lobbied NCAA Nation to support protective federal legislation targeted at the labor forces in big-time football and men’s basketball.

At the January 2024 convention, the NCAA ramped up its public lobbying campaign with aggressive and detailed appeals to stakeholders to advocate for antitrust immunity and a “no-employee” provision from Congress.

Indeed, the staging of the convention itself was built around crisis themes that channeled utilitarian arguments—particularly the claimed existential threat of employee status—and the necessity for protective federal legislation.

Note: For a discussion of legal limits on antitrust and nonprofit lobbying, see the Lobbying Tab in the Explore Menu.

The California revenue sharing bills highlight the power of Olympic sport/gender equity themes in actual legislative decision-making.

The California legislators were required to take a position and cast a vote.

The results suggest that profit athletes in football and men’s basketball face substantial obstacles to realizing their actual market value through revenue sharing.

In Congress, while the Olympic sport/gender equity issues have been discussed at a broad policy level, no specific legislation relating to college sports has made it to a committee debate or a vote.

ii. What is “Revenue Sharing” in 2024?

In late 2023 and early 2024, revenue sharing returned to the discussion over athletes’ rights.

On December 5th, 2023, NCAA President Charlie Baker released a generalized proposal (“Project D-I”) that included a component that looked like revenue sharing, but it’s still not clear how it would operate. Baker’s proposal suggested the possibility of a new Division for the “highest resource” schools (presumably a subset of FBS schools) that would deposit at least $30,000 per year for at least half of their scholarship athletes into an “education” trust fund.

That money would be distributed to all athletes in equal shares, alleviating Title IX concerns.

Baker’s proposal aligns with growing chatter in the college sports commentariat that “revenue sharing” is inevitable.

But Baker’s proposal is a far cry from the California approach that is based on distributions to sports that generate “net revenue” and would result in substantial subsidies from football and men’s basketball to “Olympic” and women’s sports athletes.

Some other “revenue sharing” proposals, like one suggested by Ohio State’s athletics director Gene Smith, would be a modest, equal share “top off” to the athletics scholarship akin to the full cost of attendance stipend and the Alston education benefit.

The Baker and Smith “revenue sharing” proposals would be deemed “educational” to align with the NCAA’s amateurism-based prohibitions on pay-for-play and would not result in employee status for athletes.

Whether proposals like Baker’s and Smith’s are a genuine move towards meaningful “revenue sharing” or instead a new shiny object to justify federal protections and immunities from Congress remains to be seen.

However, the concept of “revenue sharing” appears to be evolving through the lens of Title IX interests and NCAA/Power 5 control.

2. Employment Status

Some states have considered or enacted laws prohibiting athletes from being employees. Non-employee status is presumed in NIL laws because they uniformly prohibit universities from entering into NIL deals with their athletes, yet some NIL laws explicitly say that athletes are not employees.

After the Northwestern football team’s unionization attempt in 2014 (see Administrative Agency Tab in the Explore menu for more on the Northwestern case and athletes as employees), state legislatures in Michigan and Ohio passed amendments to their labor laws excluding full-scholarship athletes from coverage, classifying them as nonemployees.

In 2022, a Michigan legislator introduced a proposal to explicitly include athletes as employees under state labor law to allow for the possibility of collective bargaining. No action has been taken on the proposal.

3. Anti-NCAA Enforcement Laws: Due Process and NIL

States have also passed laws that directly challenge and limit the NCAA’s regulatory authority. The laws came in two waves, the first in the early 1990s, arising in the due process context, and the second in 2023, arising in the NIL context.

i. Due Process

In the early 1990s, in response to claims that the NCAA’s infractions and enforcement process denied schools, coaches, and athletes federal due process rights, several states enacted laws that imposed state-based procedural protections not permitted by NCAA rules.

The flashpoint for these laws was the NCAA’s decades-long battle against the University of Nevada Las Vegas and head men’s basketball coach Jerry Tarkanian. After an investigation into alleged recruiting violations, the NCAA instructed UNLV to punish Tarkanian and accept NCAA penalties. Tarkanian sued the NCAA in a Nevada state court, claiming he was denied federal due process rights.

The case made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1988, the Supreme Court held in a 5-4 decision that the NCAA was not a “state actor” and, therefore, not obligated to provide federal due process protections in its infractions and enforcement cases.

In 1991, the Nevada state legislature passed a law that expanded due process protections for institutions in Nevada subject to NCAA rules.

The Nevada law imposed protections not available in the NCAA infractions and enforcement process, including the right to confront all witnesses, the right to have all written statements signed under oath and notarized, the right to have an official record kept of all proceedings, or the right to judicial review of an NCAA decision.

The law also provided aggrieved parties injunctive relief, compensatory damages, and attorney’s fees. The law prohibited the NCAA from punishing schools in Nevada that complied with the law.

Legislatures in Florida, Illinois, and Nebraska enacted similar laws.

In 1991, the NCAA filed a declaratory judgment suit in federal court in Nevada—NCAA v Miller—claiming the Nevada law violated the U.S. Constitution’s Commerce Clause.

The NCAA claimed the Nevada law placed an impermissible burden on interstate commerce because it gave NCAA institutions in Nevada preferential treatment compared to states without such a law and undermined the NCAA’s uniform, national regulatory structure.

The District Court agreed with the NCAA and struck down the Nevada law.

On appeal, the 9th Circuit held the Nevada law violated the Commerce Clause.

The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

As noted in the Dormant Commerce Clause section above, the NCAA has held up Miller in the NIL debate as a pathway to achieve national uniformity in NIL regulation independent of congressional action.

ii. Anti-NCAA Enforcement Laws on NIL

In the post-Interim Policy NIL era, several states have passed or amended NIL laws designed to neutralize the NCAA’s enforcement jurisdiction and authority, including Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, and Colorado.

Texas, for example, amended its original NIL law as of July 1st, 2023, to include this provision:

“An athletic association, an athletic conference, or any other group or organization with authority over an intercollegiate athletic program at an institution to which section applies may not enforce a contract term, a rule, a regulation, a standard, or any other requirement that prohibits the institution from participating in intercollegiate athletics or otherwise penalizes the institution or the institution’s intercollegiate athletic program for performing, participating in, or allowing an activity required or authorized by this section.”

The scope of this enforcement limitation is not clear. Still, it appears to at least impair the NCAA’s (or a conference’s) ability to enforce any NIL rules or policies or punish schools for NIL activity.

However, given the NCAA’s refusal to enforce its NIL rules/policies, these provisions have little practical relevance.

States with SEC schools—Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, and Arkansas—are leading the way with new anti-NCAA enforcement laws. This suggests at least the appearance of tension between SEC-affiliated interests and the NCAA.

However, this “showdown” has the feel of a manufactured crisis to accelerate Congressional action and perhaps also resurrect the possibility of a dormant commerce clause lawsuit like the one the NCAA threatened against California in 2019 under a Miller v NCAA theory.

iii. NIL Direct University Payment Laws

On April 29, 2024, the state of Virginia passed a law that permits schools in Virginia to pay athletes directly for their NIL. The law conflicts with NCAA prohibitions on direct payments. The universities of Virginia and Virginia Tech were instrumental in getting the law passed. UVA athletics director Carla Williams said, "If this law gets us closer to a federal or a national solution for college athletics then it will be more than worthwhile. Until then, we have an obligation to ensure we maintain an elite athletics program at UVA."